Based on Toby Huff, The Rise of Early Modern Science (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

In the time between the Scientific Revolution and World War II, almost every major advance in modern science was made by scientists who were culturally European. These scientists guided us along the path from a divinely created universe with the Earth sitting placidly at its center, to a universe whose chemistry and physics were determined in the unimaginable fury of the Big Bang. They cracked the atom and the genetic code, traced human origins back to the brink of life, and made time itself malleable. They recast chemistry on atomic principles and filled in the blanks in the periodic table. They discovered the bacterial and viral causes of diseases and developed ways to fight them.

As amazing as scientific progress was during this time, it is also understandable. Each discovery opened the way for further discoveries, so scientific progress behaved like a chain reaction, or like some magisterial trick with dominos. But this explanation leaves some interesting puzzles unresolved. Why was modern science so closely associated with Europe for so long? China and the Islamic world had been at different times the most scientifically advanced parts of the world. Why did neither of them experience a cascade of knowledge like the one that Europe experienced? Why did science eventually stagnate in both of these places?

The answers to these questions have to do with social structures, not with science itself. Joseph Ben-David has argued that

…the persistence of a social activity over long periods of time, regardless of changes in the actors, depends on the emergence of roles to carry on the activity and on the understanding and positive evaluation (“legitimization”) of these roles by some social group.1

Ben-David called this process institutionalization. As an example, consider the men who dress up in strange costumes and take part in faked fights. This activity has persisted for longer than I would have thought possible because society has a role for the participants (WWF superstar), and because a social group (the fans) provides a positive evaluation of their behaviour (goes bonkers). The strange dressing / fake fighting combo has been institutionalized and will persist for as long as fans buy the tickets and raise the rafters.

The success of science in any society likewise depends upon its institutionalization. Science is institutionalized if it is integrated into society in a way that allows scientists to practice and refine their craft, train the next generation of scientists, and be recognized for their work. Recognition includes enough income and prestige to make a life of science appealing to a critical mass of scientists. Toby Huff argues that science was successfully institutionalized in Europe in the early Middle Ages, but not successfully institutionalized in China and the Islamic world during their respective periods of scientific dominance. As a result, science thrived in Europe but eventually stagnated in China and the Islamic world.

How European Institutions Supported Science

The overhaul of Europe’s legal systems during the twelfth century was pivotal for the development of European science. The new legal systems facilitated the development of the university, an institution of higher learning quite unlike any that had come before it, and gave natural philosophers unprecedented control over their craft.

Legal Foundations

Before the twelfth century there had been no comprehensive legal systems in Europe. The law consisted of a variety of overlapping and often conflicting law sources, and these laws were often trumped by the dictats of princes and kings. The idea of the law as an organized body of knowledge, held together by fundamental principles, was absent. There were no professional jurists, judges, or lawyers.

The first comprehensive legal system, canon law, appeared as a consequence of the investiture crisis (1050 – 1122), in which the Church sought to free itself from the influence of secular authorities. By the end of the crisis the Church had acquired legislative, administrative and judicial powers. The Church was the first modern state, a model for the nation states that would soon appear in Europe.

The creators of canon law (the canonists) had begun with a number of disparate and often contradictory law systems. Their aim was to deduce the common principles that underlay these systems, and to create a consistent and comprehensive system of laws built around those principles. The canonists formulated the idea of natural law to aid in this task. Natural law was based on reason and conscience, and was judged to be less compelling than divine law but more compelling than human law. Natural law was invoked by the canonists to decide what should be kept, rejected, or reformed.

The concept of natural law is the first acknowledgement that humans can use reason and conscience to decide what is just and what is unjust. It appeared at roughly the same time as other scholars were arguing that human reason is sufficient to understand the order of the universe. Europeans were gaining confidence in their intellectual power and extending its reach.

Europe’s new legal systems introduced the concept of a corporation or universitas, an entity that had the same standing before the law as a single person:

Legally a corporation (universitas) was conceived of as a group that possessed a juridical personality distinct from that of its particular members. A debt owed by a corporation was not owed by the members as individuals; an expression of the will of the corporation did not require the assent of each separate member but only of the majority. A corporation did not die; it remained the same legal entity even though the persons of the members changed.2

The corporation had a legal right “to own property, to have representation in court, to sue and be sued, to make contracts, to be consulted when one’s interests were affected by the actions of others, especially kings and princes.”3

Examples of corporations included guilds, businesses, cities and villages, monasteries and convents, states, and schools. The term universitas, meaning “totality” or “whole,” initially referred to a guild that represented all of the practitioners of a craft, but over time it came to be applied exclusively to guilds of scholars of a particular type (say, medicine). The term studium generale was used to refer to all of the scholars collectively, and more closely corresponds to our use of the word “university.”

Several aspects of the corporation would have major consequences for Europe. First, the corporation had to be represented, before the courts and in all of its dealings, by one individual. That individual was elected by all of the members of the corporation. This practice marks the beginning of political representation. The English would take the next step, political representation within a Parliament, in the thirteenth century. Second, the powers of the representative were clearly delineated by explicit powers of attorney, foreshadowing the idea of constitutional government. Third, each corporation had a jurisdiction within which it was empowered to act. It could write rules and regulations to control its members, and to determine the way in which it would carry out its operations.

The legal concept of the corporation turned Europe into a network of overlapping and competing (and sometimes head-butting) jurisdictions. The importance of this innovation is best understood by comparing Europe to China and the Islamic world. There was precisely one jurisdiction in China: that of the emperor. Nothing was outside his purview. There was also precisely one jurisdiction in the Islamic world: that of the faith. There was no separation of the temporal and spiritual spheres, and “the law of the realm consisted precisely of those commands the believer must follow if he was to pass the reckoning on the day of judgment.”4 Neither society was able to institutionalize science.

Universities

The concept of a corporation made the institutionalization of science possible; the university was the vehicle through which institutionalization actually occurred. Universities provided natural philosophers with a livelihood, and allowed them to practice their craft, set the standards for that craft, and train the next generation of scholars. Universities also exposed all educated persons to natural philosophy, ensuring its social acceptance.

Higher education in the early Middle Ages had been carried out by “cathedral schools” that were primarily intended to train clergymen. These schools emphasized subjects that would be of value to a member of the clergy (such as Latin and rhetoric) but paid little attention to ideas of a scientific or mathematical nature. They would also have taught the doctrine of occasionalism (imported from the Islamic world) under which God is the immediate cause of every event.

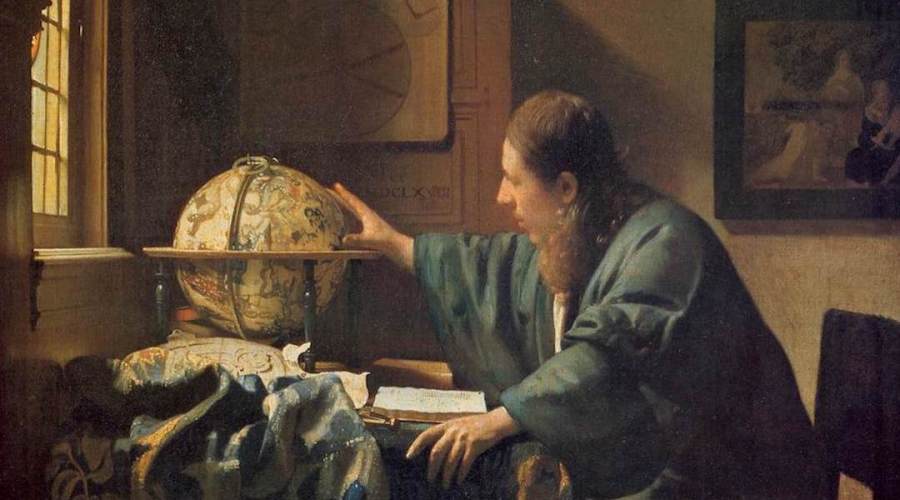

Europeans of this time were aware of Greek and Islamic scholarship, but their knowledge of it was fragmentary. That situation would change as they pushed back the boundaries of the Islamic world in the eleventh century. Toledo fell to the Christians in 1085 as part of the Spanish reconquest, and the island of Sicily was retaken by Christians in 1091. Both places had extensive libraries containing Arabic translations of Greek works, commentaries on these works by Muslim scholars, and original Muslim research. The Greek works were mostly Athenian, with a heavy emphasis on Aristotle. As the books were translated from Arabic into Latin (a task to which some scholars devoted the remainder of their lives), hundreds of years of natural philosophy became available to European scholars. They spent decades studying and organizing these books and writing commentaries on them. European scholars also engaged in the philosophical debates that would ultimately reconcile natural philosophy with Christianity.

When universities began to appear in the middle of the twelfth century, their curriculum was built around the works of Aristotle and the “new” way of thinking that was to be found in them. Some universities grew out of cathedral schools, but many were entirely independent ventures. By 1200 there were universities in Bologna, Paris and Oxford. More than seventy universities were founded over the next 300 years.

In 1500 the largest universities were taking in 500 new students each year. There were usually four faculties. Students first entered the arts faculty, where they studied Aristotle and natural philosophy. Students who successfully completed the arts curriculum could enter the faculty of theology, law or medicine. This schema ensured that everyone who went to university — including every aspiring theologian — became familiar with natural philosophy.

The university’s jurisdiction was higher education. The university designed the curriculum, and the university gave degrees signifying the holder’s competence in his area of specialization. Society’s recognition of that jurisdiction gave natural philosophers a place in society. While there were certainly natural philosophers who were not associated with universities, it was the university that integrated natural philosophy into Europe’s social fabric.

Border Skirmishes

If there are many jurisdictions, there will be disputes about where one jurisdiction ends and another begins. Natural philosophy and its successor, science, have often encountered this problem.

In 1215, for example, the Pope banned the reading and teaching of Aristotle at the University of Paris. The ban must have been imposed at the request of the Bishop of Paris, because it did not apply to other universities. It was rescinded by 1255 at the latest, and it is unlikely that it was ever entirely effective.

In 1277 the Bishop of Paris issued a condemnation of 219 propositions thought to be included in, or implied by, the teaching of the University of Paris. One of these propositions was Aristotle’s assertion that the world is eternal, which clearly contradicts the Church’s assertion that God brought the world into being and will bring it to an end. Another condemned proposition was Aristotle’s claim that a vacuum could not occur naturally, which implies a limit on the power of God. Although the Bishop’s condemnation was never repealed, it appears to have had little impact on the university. The arts faculty believed that natural philosophy was the right way to understand the world, and continued to advocate it. They had jurisdiction over the university’s curriculum, the Church did not, and in the end the arts faculty won out.

Such skirmishes have continued over the centuries. Among the most famous instances are the trial of Galileo and the reception of Darwin’s theory of evolution. Skirmishes continue to this day, particularly with respect to the teaching of evolution in schools. Science has not been derailed by them.

How Islamic Institutions Impeded Science

Islam’s “golden age of science” was a period of intense activity. It began during the caliphate of al-Mamun (r. 813-833), who supported the collection and translation of Greek philosophy and science into Arabic, and also had works from India and Central Asia collected and translated. These works stimulated Islamic scholarship. Scholars read and organized them, wrote commentaries on them, and used them as the foundation for their own research. Islamic scholars soon led the world in several fields, including optics, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine.

One of the Islamic world’s most significant innovations was the experiment. The Optics of al-Haytham, written in the early eleventh century, was based on simple, clearly defined experiments. It significantly influenced Roger Bacon and other contemporary Western scholars after its translation into Latin in the middle of the twelfth century. The power of medieval experimentation is shown by the independent and nearly simultaneous (about 1304) demonstrations, by Kamal al-Farisi in the East and Theodoric of Freiburg in the West, that the rainbow is the result of two refractions and one reflection inside drops of rain. Islamic scientists also employed experiments in medicine, where al-Razi (d. c. 925) used controlled experiments to determine the efficacy of herbal treatments, and in astronomy, where predictions were routinely tested against new data.

The golden age ended with a whimper rather than a bang. Islamic science became less adventurous and less innovative after the twelfth century, although significant discoveries continued to be made, particularly in mathematics and astronomy. The astronomer Ibn al-Shatir (d. 1375), for example, constructed a geocentric model of the solar system that was mathematically equivalent to the heliocentric model of Copernicus (d. 1543). Nevertheless, scientific leadership had certainly passed from the Islamic world to the West by the sixteenth century.

Toby Huff argues that the slowdown in Islamic science occurred because scientists were unable to establish their autonomy. Islam’s claim is that it is a complete way of life: nothing is outside of its jurisdiction. This claim impacted scientists in a number of ways.

First, Islamic scientists, unlike their Western counterparts, could not establish any theological wiggle room. Western theologians and natural philosophers believed that the world was created by God according to a plan of his own design, and that he would not now deviate from that plan. Every event in the observed world followed from natural (as opposed to supernatural) causes, and natural philosophers were free to make causal claims about these events. The God of Christianity was essentially banished to the margins of his own creation. By contrast, the God of Islam was always and everywhere present. Al-Ash’ari (d. 935) propounded the doctrine of occasionalism, under which the world was held together from moment to moment by the will of God. Effect followed from cause only if God willed it to be so. Occasionalism was still a part of Islamic theology when Al-Ghazali (d. 1111) wrote The Incoherence of the Philosophers, his powerful attack on Aristotelian philosophy as practiced in the Islamic world:

According to us the connection between what is usually believed to be a cause and what is believed to be an effect is not a necessary connection; each of the two things has its own individuality and is not the other, and neither the affirmation nor the negation, neither the existence nor the non-existence of the one is implied in the affirmation, negation, existence or non-existence of the other — for example, the satisfaction of thirst does not imply drinking, nor recovery the drinking of medicine, nor evacuation the taking of purgative, and so on for all the empirical connections existing in medicine, astronomy, the sciences, and the crafts. For the connection between things is based upon the power of God to create them in successive order, though not because this connection is necessary in itself and cannot be disjointed — on the contrary, it is in God’s power to create satiety without eating, and death without decapitation, and to let life persist despite decapitation, and so on with respect to all connection.5

Islam did not draw back to create intellectual room for the philosophers. Aristotle’s view that the world is eternal was an irritant in the West; for Islam, it was an assault on its integrity.

Second, Islamic law did not recognize the possibility of competing jurisdictions. The Quran and the hadiths (the sayings of Mohammed) were held to constitute a complete legal system: nothing could be added to it and nothing could be taken away. A legal scholar could interpret the law when its application in a particular instance was unclear, but unlike English common law, that interpretation did not establish a precedent upon which new law could be built. Islamic law did not include any concept equivalent to the European corporation, and therefore lacked the associated concept of jurisdiction.

Third, and unsurprisingly in light of the legal and theological constraints, the Islamic world did not establish institutions in which scientists could engage in open and free investigation. Its institution of higher learning was the madrasa, which was designed for the training of the religious and legal scholars who were the moral and ethical guides of Islam. Nothing that was inimical to Islam could be taught there. Aristotelian philosophy and the natural sciences were not part of the curriculum, which instead focussed on such subjects as law, Quranic studies, Arabic grammar, and practical arithmetic.

The Islamic golden age produced a line of important scholars who were deeply influenced by Aristotle, including al-Kindi (d. ca. 870), al-Farabi (d. 950), al-Razi (d. ca. 925), Ibn Sina (d. 1037), al-Baghdadi (d. 1152), Ibn Rusd (d. 1198). They supported themselves by working as physicians or judges, or were supported by wealthy benefactors. The option of merging their scholarship with their professional life was not open to them, as it was in the West.

Sabra has argued that Islamic science went through three phases. In the first phase, exposure to foreign scholarship, particularly that of the Greeks, opened new horizons for Islamic scholars. They responded by producing a wide variety of innovative science and philosophy, but there was continuing friction with religious scholars. In the second phase, which Sabra calls naturalization, Islamic scientists became more conscious of the need to harmonize science with Islam. Al-Ghazali’s The Incoherence of the Philosophers and Ibn Rusd’s The Incoherence of the Incoherence were written during this phase. The former work argued that Aristotelian philosophy was inconsistent with Islam, while the latter attempted to refute al-Ghazali’s arguments. Al-Ghazali prevailed in the East, while Ibn Rusd’s collective works strongly influenced Western science. The scope of Islamic science narrowed during this phase. As Sabra explains,

For the religiously committed Ghazali this means, not only that religious knowledge is higher in rank and more worthy of pursuit than all other forms of knowledge, but also that all other forms of knowledge are subordinate to it…Thus, among the non-revealed forms of knowledge: medicine is necessary only for the preservation of health; arithmetic for the conduct of daily affairs and for the execution of wills…There is only one principle that should be consulted whenever one has to decide whether or not a certain branch of learning is worthy of pursuit: it is the all-important consideration that “this world is the sowing ground for the next.”6

The third phase consisted of the long dénouement of Islamic science.

Al-Shatir is credited with having produced in the fourteenth century a geocentric model of the solar system that is mathematically equivalent to the Copernican model of the sixteenth century. Why did he not make the great leap to a heliocentric model? Perhaps the answer is that until the time of Galileo, the astronomer’s role was not to understand the nature of the solar system, but to observe and predict. A model that fit the data was all that was required. And yet this answer seems unsatisfactory. Did al-Shatir never notice that the retrograde motion of Mars would be more easily explained if the earth also moved? Or did he notice, and decide not to pursue an idea that would lead him into conflict with the religious scholars?

How Chinese Institutions Impeded Science

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote, “Printing, gunpowder and the compass: these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world.” All three of these inventions appeared first in China, along with a great many

others.7 China was an early leader in science as well as technology, but by the eleventh century, it lagged behind both the Arab world and the West in the “core” areas of astronomy, optics, physics, and mathematics.8 It lacked knowledge of deductive geometry and trigonometry, despite being in almost constant contact with Indian and Arab scientists. China would not become current in the sciences until the seventeenth century, and even then would not contest the West’s leadership.9

Huff argues that this long period of stagnation occurred because China, like the Islamic world, failed to institutionalize science. Scientists in the Islamic world could not become autonomous because there was only one jurisdiction, that of Islam. Scientists in China could not become autonomous because there was only one jurisdiction, that of the emperor.

Both China and Europe were feudal states at the beginning of the Song dynasty (960-1279), but their political institutions strongly diverged from that point forward. In Europe the legal revolution of the twelfth century led to the development of autonomous institutions and hence to the decentralization of power within each country. The first Song emperor, Taizu, pushed China in the opposite direction, toward greater centralization of power. China remained rigidly centralized through both the Song dynasty and Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The Ming dynasty ended just a few decades before England’s Glorious Revolution, which protected citizens from the depredations of the king and entrenched their right to representative government. In China the emperor remained an absolute monarch.

The first Song emperor, Taizu, ruled a country that had collapsed at the end of the Tang dynasty (907) and had then been reunited through decades of war. He recognized that the regional warlords who had helped to unify the country were now the greatest threat to its unity. Each had an army and a geographic base, and each was a potential rebel. Taizu persuaded the warlords to retire, with generous rewards, and assigned their administrative functions to civil servants. He also ensured that the majority of the new civil servants would be selected on merit, as measured by their performance on civil service examinations.

The civil service subsequently evolved into a complex hierarchy in which information was passed upward and decisions were passed downward. At the bottom of the hierarchy was the district magistrate, who was at once judge, financial officer and sheriff. The next level up from the district was the prefecture. Officials at this level were appointed so that their jurisdictions overlapped. There were also roaming officials who wrote independent assessments of each prefecture’s situation, and censors who had broad powers to investigate the public and private activities of all officials. This web of authority was designed to ensure that no territorial official could threaten the stability of the country by developing an independent power base.

The examination system ultimately became the only way to enter the civil service. Passing the district exams and then the prefectural exams made a man a “cultivated talent.” Passing the provincial exams (offered every three years) made him a “recommended talent.” Finally, passing the exams in the capital made him a “presented scholar” — and only then eligible for a civil service appointment.

The exams were based on the works of Confucius. Preparation for the exams began in childhood, with lessons in calligraphy and writing classical poetry. Children began to memorize the Confucian classics long before they were able to understand them. (Preparation for the exams after 1787 required the memorization of more than 500,000 characters of text.) As children grew older, they began to learn the meaning of the classics and prepare to answer examination questions based upon them. Most candidates received instruction in private academies that followed an officially prescribed curriculum.

The exams were highly stylized and rigidly graded. Since it was not uncommon for a candidate to fail the provincial exams a dozen times, candidates could devote decades of their lives to passing the exams. There was, however, no shortage of candidates because the civil service was one of the few opportunities for upward mobility.

The examination system had some beneficial effects on Chinese society. Its rigour meant that only “the best and the brightest” were recruited into the civil service. It also ensured that all well-educated people — whether or not they attained their goal of becoming “presented scholars” — were imbued with Confucian ethics. Confucianism’s emphasis on traits like loyalty, integrity and benevolence contributed to the stability and harmony of Chinese society.

On the other hand, the examination system probably squandered a significant part of China’s human talent. The system winnowed down the number of candidates until it roughly matched the number of new civil servants required. The winnowing was accomplished by testing the candidates on such things as their ability to compose highly stylized “eight-legged essays.” These skills were essentially uncorrelated with the skills needed to be, say, a successful district magistrate. If the examinations had ended when there were two or three times as many candidates remaining, and if the civil servants had been chosen from this pool by lottery, the quality of the successful candidates would not have been significantly different, and the unsuccessful candidates would have been spared years of unproductive study.10

The dominance of the civil service within Chinese society, coupled with the upward mobility that it offered, made it an attractive option for young and capable men. Candidates for the civil service had a clear path to follow, and there were government-sanctioned academies that existed solely to push them along that path. It must have been difficult for any of “the best and the brightest” to escape the civil service funnel. On the other hand, a career in science would have been difficult to achieve. Exams were occasionally held to fill government positions in mathematics and astronomy, but these exams were not regularly scheduled. There was no established curriculum in the sciences, and there were no institutions of higher learning that could prepare a student for a career in science. The absence of such institutions also meant that there were few opportunities for a career in science outside of the government bureaucracy.

Chinese philosophy posited a connection between heavenly and earthly events. The link between the heavens and the emperor was imagined to be particularly strong, with disorder in the heavens signalling a fault in the emperor’s conduct. Astronomy and timekeeping were therefore matters of state, requiring a high degree of circumspection. The free exchange of ideas that characterized European scholarship did not occur, and unconventional thinking was discouraged.

Scientists in China were simply unable to establish the autonomy required for science to be institutionalized. As in the Islamic world, its bright beginnings gave way to a long period of stagnation.

Science and Society

There is a tendency to think that science’s dominant role in society was inevitable, that its insights were so valuable that no society could ignore them. Yet, there are enclaves even within Western society, such as the Amish and the Mennonites, that actively shun much of modern science and technology. These groups decided many years ago that the benefits of science were outweighed by the attendant social disruption. The growing gap between the lives they lead and the lives led by outsiders has not caused them to question their decision.11 The establishment of science within a society is not inevitable: it is something that must be negotiated. That negotiation was successful in the West, and the West owes a large part of its prosperity to that success.

- Joseph Ben-David, The Scientist’s Role in Society (Prentice-Hall, 1971), quoted in Huff, p. 17. ↩

- Pierre Michaud-Quantin, Universitas: Expressions du mouvement communautaire dans le moyen-age Latin (J. Vrin, 1970), quoted in Huff, p. 133. ↩

- Huff, p. 134. ↩

- Huff, p. 120. ↩

- Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, quoted in Huff, p. 113. ↩

- I. Sabra, “The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Science: A Preliminary Statement,” History of Science 25 (1987), p. 239. Quoted in Huff, p. 87. ↩

- Many Chinese technologies, including paper and the heavy plow, diffused into the West, while others were independently developed. Movable type appeared first in China, but was independently developed in Europe. Gutenberg’s printing press (which automatically inks the pages) and his moulds for casting type have no eastern antecedent. The compass also appears to have been independently developed in the West. The first records of its use in navigation in the West predate all Arab and Persian references to its existence, so the compass is unlikely to have reached the West through diffusion. ↩

- Huff, p. 242. ↩

- Huff, p. 248. ↩

- The examination system is essentially an example of the rent-seeking problem, in which agents compete for the possession of certain rents, and are able to improve their chances of gaining the rents by outspending their competitors. (For example, the rents could be the benefits associated with some public office, and the candidates could be able to improve their chance of being elected to that office by spending more on advertising.) Under some circumstances the total amount spent by the agents will be equal to the value of the rents, so that the agents as a group are neither better nor worse off. (In the election, the winner gets the benefits of the office while the losers are stuck with their campaign debts. The total campaign debts are equal to the value of the office.) ↩

- It has been estimated that more than 80% of Amish youths choose to become full members of their church and emulate their parents’ lifestyle. ↩