Based on Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization (Columbia University Press, 1991), and Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development (Cambridge, 2024)

Japan’s growth in the postwar period was unprecedented — no other country had grown so fast for so long — but its growth was soon bettered by Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea. These four countries are popularly known as the “Asian tigers,” but this designation masks substantial differences between them. Hong Kong and Singapore are city-states that served as entrepôts during the colonial era. They expanded and diversified their activities as world trade grew in the late twentieth century, but their essential character has remained the same. Taiwan and South Korea, on the other hand, were predominantly agricultural countries with almost feudal social structures until the beginning of the twentieth century. They completely transformed themselves over the course of the century, becoming industrial countries able to compete on world markets. Taiwan Semiconductor is a leader in semiconductor manufacturing, while Hyundai, LG and Samsung are brand names known around the world. Hong Kong and Singapore cannot boast of any equally recognizable corporations.

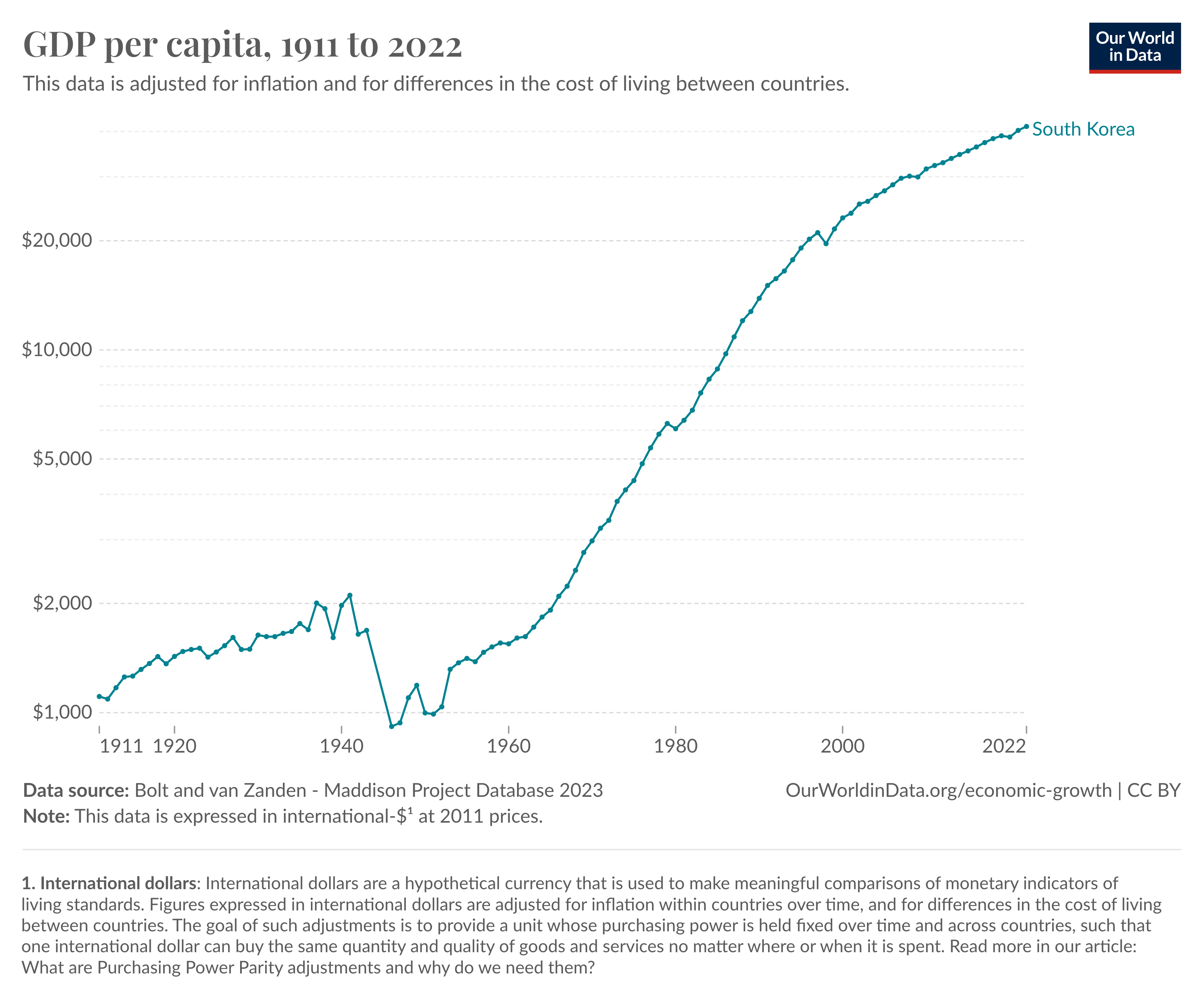

This post and the next (here) examine the economic transformations of South Korea and Taiwan. The figure above shows their growth in the postwar period. The GDP per capita of both countries now exceeds that of Japan, their one-time colonial master. Both countries were aware of Japan’s deliberate transformation from a feudal state to one of the world’s leading economies, and both countries adopted elements of Japan’s economic policies. But each country had its own unique history and “initial conditions,” and each country developed in its own way. In the case of South Korea, economic development was shaped by its devastating civil war, and more broadly, by the Cold War of the 1950s.

Korea under Japanese Control

Korea’s standard of living declined during the nineteenth century, and high mortality rates caused the population to fall. The centuries-old Chosŏn dynasty was failing, with weak kings under the control of more powerful private interests. A peasant rebellion in 1894 provided the pretext for Japanese intervention. The Japanese then stage-managed reforms that shifted power away from the dynasty and institutionalized their own influence. An unequal treaty in 1910 replaced influence with control, ceding “all rights of sovereignty over the whole of Korea” to Japan.

The Japanese had very deliberately reconstructed their own country after the Meiji restoration, and now engaged in an equally deliberate reconstruction of their new colony.

One important project was to improve infrastructure: railway lines were extended, and roads and harbors and communication networks were improved, which rapidly integrated goods and factor markets both nationally and internationally. Another project was a vigorous health campaign: the colonial government improved public hygiene, introduced modern medicine, and built hospitals, significantly accelerating the mortality decline set in motion around 1890, apparently by the introduction of the smallpox vaccination. The mortality transition resulted in a population expanding 1.4% per year during the colonial period. The third project was to revamp education. As modern teaching institutions quickly replaced traditional schools teaching Chinese classics, primary school enrollment rates rose from 1 percent in 1910 to 47 percent in 1943. Finally, the cadastral survey (1910-18) modernized and legalized property rights to land…These modernization efforts generated sizable public deficits, which the colonial government could finance partly by floating bonds in Japan and partly by unilateral transfers from the Japanese government.1

The Japanese nevertheless maintained a clear distinction between Korea and the homeland. In particular, Korea’s economic policy was designed to fulfil the homeland’s needs. For the first decade or so, Japan primarily viewed Korea as a source of rice. The cadastral survey was a step towards extracting as much rice as possible from Korea. It was not beneficial to Korea’s farmers — many peasants became landless, and even some landlords had their land confiscated. As well, land that had been held by the Chosŏn state was claimed by the new colonial government or sold cheaply to Japanese colonists.2

Japan also wanted Korea to be a market for its own manufactured goods, and to that end, it clamped down on Korea’s manufacturing. The colonial government gave itself the authority

…to control, and to dissolve if necessary, both new and established businesses in Korea.3

No Korean was permitted to start a factory without permission (and the permission was almost always denied) and direct private Japanese capital inflow was discouraged…Through 1919, therefore, those industries that thrived in colonial Korea were mostly household industries that did not require company registration…Large-scale factories employing more than fifty workers numbered only 89 (and were mostly Japanese owned), even as late as 1922. Industrial production…was mostly in cottage industries such as dyeing, papermaking, ceramics, leather processing, rice milling, soy sauce making, brewing, rubber shoemaking, candles, etc.4

Firms employing fewer than fifty workers accounted for 94.5 percent of industrial employment in 1929.5

Japan’s attitude toward Korean industrialization changed in the 1930s.

The precipitating factor was the deterioration of the Japanese rural economy, which, to reverse the trend, required a halt in the expansion of Korean rice production. More important, however, was a complex set of policy changes occurring in Japan as a response to domestic crisis and the rapidly fluctuating international environment: the decision, following the boycott of Japanese products by other nations through tariffs and quotas, to pursue autonomous development, to create a self-sufficient economy within its bloc of influence.6

Japan’s slide towards militarism was also a factor. Japan’s domestic industry could not provide all of the necessary armaments, so the colonies had to provide a range of goods, from raw materials through intermediate goods to final goods.

Korea was a good place for Japanese firms to set up a business. Taxes were low, regulation and worker protection were undemanding, labour and power were cheap, the necessary infrastructure was either in place or being built, and the colonial bureaucrats were not corrupt. Only the policies of the colonial government had stopped them from investing. Now that these policies had been abandoned, Japanese firms, led by the business conglomerates known as zaibatsu, started to operate in Korea. In 1940, the zaibatsu contributed three-quarters of Korea’s capital investment.7

This investment was often indirectly funded by the Japanese government.

The older and better established zaibatsu could depend on their own banks, insurance, and trust companies. But, for the shinko (new), the most adventurous zaibatsu, the source of capital was the Industrial Bank of Japan (IBJ) and the government. The former, organized in 1900 to meet the industrial sector’s demand for long term capital, was by the 1930s financing government-sponsored munitions and overseas projects…After 1937, however, the Industrial Bank began to handle a large part of financing of the new zaibatsu. The Ministry of Finance might order the bank to advance funds to these zaibatsu, or to subscribe, underwrite, or buy securities so as to further essential industrial production. The government would in turn make good any loss incurred by the IBJ in the process, and also restricted corporate dividend payments in order to encourage reinvestment…The Ministry of Finance was [also] able to…compel commercial and private banks to lend to specific companies in the target sector. Business and financial interests were not reluctant to go along with the financial policies of the state, for again, any loss suffered by the banks through the nonperforming loans would be indemnified by the state.8

Backed by the Japanese state, Korea achieved high rates of economic growth throughout the 1930s. Value-added grew by 10% per year in the manufacturing sector and by 19% in the mining sector.9

South Korea, when it came into being, did not greatly benefit from this early industrialization. Much of the heavy industry was in North Korea, and other industrial facilities were destroyed during the Korean War. Moreover, the Japanese firms had been reluctant to employ Koreans in management positions, so Korean entrepreneurship had not developed.

On the other hand, some aspects of colonial policy were revived during South Korea’s era of rapid growth. They include: authoritarian government; government pressure to allocate resources to particular sectors and projects; collusion between the government and business conglomerates; government control of bank lending practices. All of these things were fundamental to President Rhee’s and General Park’s economic policies.

The Division of Korea

At the end of World War II, the Allies resolved that Japan should lose all of the territories that it had taken by force. They decided that Korea would be placed under a brief trusteeship, from which it would emerge as an independent country. Korea was split at the 38th parallel for administrative purposes, with the Soviets controlling everything to the north of this line and the Americans controlling everything to the south.

The goal of a unified and independent Korea was soon derailed by geopolitics. The Soviets wanted to expand communism’s domain, and to that end, they set up a provisional government in the north under the leadership of Kim Il Sung. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established in September 1948. The Americans suppressed communism in the south and pushed for UN-supervised elections. These elections resulted in the establishment of the Republic of Korea under the leadership of Syngman Rhee in August 1948.

Both leaders were opposed to the division of the country, but neither leader was wiling to make ideological compromises. Border skirmishes became commonplace. In June 1950, a deep incursion of North Korean forces into the south led to the Korean War. A UN-authorized coalition, predominantly American, intervened on behalf of South Korea, and China intervened on behalf of North Korea.

The North Koreans attempted to absorb all of South Korea, and once the war had turned in his favour, Syngman Rhee wanted to continue it until all of North Korea had been taken. But neither side was strong enough to control the whole peninsula, and after three years of fighting, the war’s front stabilized near the 38th parallel. The warring parties agreed to an armistice in July 1953. The armistice has never been replaced by a peace treaty.

A common practice is to refer to the south as Korea and the north as North Korea or the DPRK. I will adhere to this convention henceforth.

The Economics of Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee continued as president of Korea until 1960, when the student-led April Revolution precipitated his resignation. The students protested that he was unfit for the presidency because he was autocratic, corrupt, and condoned political violence — all of which was true. But he was also an ardent nationalist, and his nationalism drove his economic policies.

Rhee held the presidency at the height of the Cold War. The American policy for the containment of communism in East Asia had two components. First, a prosperous, stable and democratic Japan would showcase the possibilities of Western liberalism. Second, a militarized frontline would be established and held. It would run from Korea through Japan and Taiwan to Vietnam (which was split into two parts, a communist north and a nominally democratic south, in 1954). Billions of dollars of American aid were needed to sustain this policy. Some of the aid was military, but much of it was civil, intended to prop up national economies and maintain social stability.

Korea had always been a poor country. The dislocation and destruction caused by Japan’s defeat and the Korean War had shattered it completely.

Since Korea was a smouldering ruin in 1953, the economic agenda was survival and respite from the ravages of war; from 1945 to 1950, the upward spiral of wholesale prices was 70,000 percent; the war damage was equivalent to wiping out nearly three years of GNP, not to mention the lingering wartime psychology that fed hoarding and speculation.10

In this environment, American aid was a substantial and essential component of economic activity.

The average annual inflow of aid from 1953 through 1958 was $270 million excluding military assistance…This was nearly 15% of the average annual gross national product (GNP) and over 80% of foreign exchange.11

The role of aid in providing foreign exchange was critically important: Korea earned little foreign exchange through its exports, and without foreign exchange, it could not purchase goods abroad — no grain, no fertilizer, no machines or equipment.

Rhee continually pressured the Americans to keep the aid flowing, but there was fundamental disagreement as to what should be done with it.

Japan was the hinge of the Americans’ containment program. It was still recovering from the devastation of World War II and had not yet begun its “miracle growth” phase, so the Americans’ first concern was to strengthen its economy. They pressed for the resurrection of a wartime trade organization, the Co-Prosperity Sphere, as a means of ensuring that Japan had markets for its goods. The Sphere’s member states would be Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and a few Southeast Asian countries. Japan would export manufactured goods to the other members, and import from them raw materials and lightly processed goods. Under this scheme, much of Korea’s scarce foreign exchange would go to the purchase of Japanese manufactures. Rhee complained,

The American policy [is] to secure two dollars of benefit — one for Japan and one for Korea — from every dollar expended.12

[Korean] recovery is slowed as we are expected to buy more from Japan, and accordingly to use less to build up our own productive facilities. This has an immediate effect of once more placing our economy at the mercy of the Japanese.13

It was in reaction to this proposal that Rhee initiated a program of import-substitution industrialization. Korea would not import more manufactures: it would import less.

The bulk of American aid went to satisfying American priorities, but Rhee’s relentless advocacy ensured that some portion of it went to financing investment. To get the most from this aid, the exchange rate was set so that it undervalued the US dollar, or equivalently, overvalued the Korean won:

In 1957, for instance, the official exchange rate was 500 won to a dollar when the real value of the dollar was estimated to hover around 800 to 1,000 won.14

This policy drastically reduced the cost (measured in domestic currency) of importing intermediate goods and capital goods, thereby facilitating the expansion of domestic industry. The same policy made foreign goods cheap relative to domestic goods, so policies that protected domestic manufacturers were implemented: tariffs made foreign goods more expensive, and quotas limited their market penetration.

Rhee’s government also intervened in credit markets to favour businesses that were willing to engage in import substitution. The credit markets themselves were wildly out of equilibrium. The government’s tax revenues did not cover its expenditures, even with the help of foreign aid, so it printed money to cover the shortfall. Money printing led to inflation. Bank interest rates were capped at a level below the inflation rate, so the real interest was negative — in real terms, the banks (which were state-owned until the late 1950s) were paying the borrowers. Not surprisingly, the demand for loans exceeded the supply. The government directed loans toward businesses that would invest in import-competing industries.

Given the small size of the manufacturing sector, Rhee’s import substitution policies could not be expected to generate the kind of record-breaking aggregate growth rates that Korea would experience in the 1970s and 1980s.15 Their impact on the economy was nevertheless clearly discernible. The average annual growth rate of the manufacturing sector between 1953 and 1960 was 11.8%.16

Eventually, the manufacturing sector had grown so much that the domestic market for some goods was saturated. Firms began to look for foreign markets for their goods. Exports, which had been stagnant until 1958, began to grow. But they grew from such a small base — exports were about 1% of GDP in 1958 — that their growth had a negligible impact on Korea’s aggregate growth rate.

Regime Change

Rhee’s government favoured not just particular sectors but particular businessmen. Favouritism could take many forms. The government could ensure that a firm had preferential access to credit on generous terms.17 Or it could allocate a tranche of foreign exchange to a firm, allowing it to buy foreign goods cheaply (because the foreign exchange was purchased with overvalued won) and then resell them on the domestic market at substantially higher prices. The government could also sell assets or purchase goods on terms that favoured the firm, or ensure that a firm received a subsidy or a tax exemption.

An early instance of the government enriching particular businessmen was the sale of the industrial properties that had been confiscated from the Japanese at the end of World War II.

Estimated at 85 percent of the national wealth, and including 3,551 operating plants and firms, land, infrastructure, and inventories, [their] gradual auction through 1957 proved to be the greatest bargain in history; small-time businessmen who cultivated government connections could now claim ownership of large factories, with inflation taking care of the cost.18

For example, one textile plant was

…valued at 3 billion won in 1947. It was later appraised down to 700 million won, and then auctioned off at 360 million won: a mere one eighth of the original price and a half of the re-appraised price. Payments were to be in annual installments stretching fifteen years…In those fifteen years, however, the price [level] jumped 300 times, and so the factory was a give-away.19

The businessmen repaid favours with cash donations to Rhee’s party. Cash, along with the support of the police and military, kept Rhee in office.

In the end, angry protesters defied the police and the military stayed on the sidelines. Rhee resigned, and the constitution was revised to create a parliamentary system of government in which the prime minister, not the president, held effective power. Chang Myon became Korea’s first prime minister, but less than a year later, he was ousted in a military coup led by General Park Chung Hee. Park held power from 1962 until 1979, when he was killed by an angry subordinate.

The Era of Rapid Economic Growth

The economy grew exceptionally quickly during Park’s rule: the average annual growth rate of GDP per capita was 8.5% between 1963 and 1979. This growth was accompanied by extensive restructuring, as the share of manufacturing in total value-added rose from 13.6% to 24.2% over the same period.20

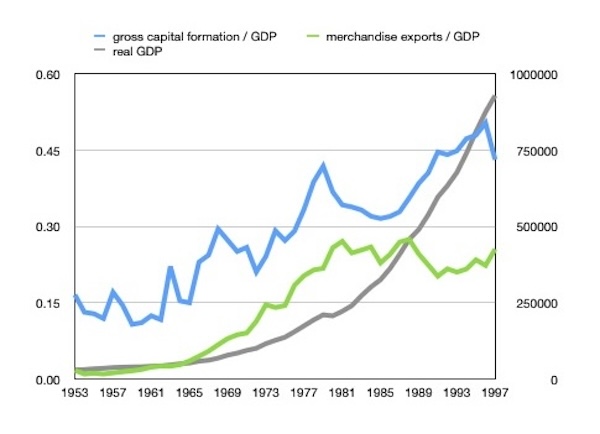

Korea’s economic growth in this era has often been described as “export-led,” but this designation is misleading. Park did pressure firms to increase their exports, and exports did grow, but export growth did not drive GDP growth. The figure below shows the shares of investment and merchandise exports in GDP (plotted against the left axis) and real GDP (plotted against the right axis).21 The shares of exports and investment grew by a factor of roughly 2.5 between 1962 and 1968, but investment had a much greater impact on output because its initial share was so much larger. Investment was 12% of GDP in 1962, growing to 30% in 1968. Exports were 2.5% of GDP in 1962, growing to 6.8% in 1968. Exports were simply too small to have had a substantial impact on aggregate economic activity. Of course, the two were linked. Korea systematically invested in facilities large enough to achieve economies of scale, which usually meant that much of their output would have to be exported.

Was there something in South Korea’s initial state that predisposed it to rapid growth? Dani Rodrik has identified two factors,22 and two more have been suggested.

Relatively Equal Income Distribution

If a society’s income distribution is too inequitable, there will be pressure for the government to undertake redistributive policies. These policies have incentive effects — people adjust their behaviour so that they gain more or lose less — which lead to a misallocation of resources and slower growth. As well, if the government involves itself in the detailed workings of the economy (as the Korean government did), redistributive policies shift the government’s attention away from the pursuit of economic growth. If the society’s income distribution is relatively equal, on the other hand, the government will be able to concentrate on promoting economic growth. Korea was in the latter category: its income distribution was relatively equal, and there was little pressure on Park to deviate from his declared policy of growing and restructuring the economy.

Korea had not always had an equitable income distribution. As late as the 1940s, it was an agricultural country organized in an almost feudal fashion, with a few rich landlords and many poor (and often landless) peasants. The Farmland Reform Act (1949) sought to improve the peasants’ welfare by forcing landlords to sell land to the government, which would then re-sell it to peasants at low prices. Many tenant farmers became the owners of small quantities of land. Spared the burden of rent, their harvests supported a significantly better standard of living. However, the landlords were harmed far more than had been intended.

Landlords sold about half of their lands directly to peasants…[but the] direct sales were at bargain prices, often by a wide margin. Also, the redistribution through government mediation resulted in fatally eroding landlords’ interests as the delay in payments with the Korean War, combined with high inflation, drastically reduced the real value of the “land compensation securities” [that] the government had distributed to landlords in exchange for their land…[The] landlord as a class was wiped out when the reform was over.23

The upper tail of the income distribution was further diminished by the wealth destruction associated with the Korean War. Korea’s income distribution, having been squeezed at both ends, was more equitable than that of most late-industrializing countries.

Well-Educated Population

A well-educated labour force “makes investment more productive, facilitates the transfer and adoption of advanced technology from abroad, and enables the establishment of a meritocratic, efficient, and capable pubic administration.”24 Education also makes people more malleable, smoothing the transition from a predominantly agricultural society to an urban and industrial society.

Korea’s emphasis on education began immediately after its liberation from the Japanese. The adult literacy rate was only 22% in 1945, but jumped to 71% in 1960 and 88% in 1970.25 The education system continued to evolve in order to meet the needs of industry.

Authoritarianism

Conventional trade theory argues that countries should export the goods in which they have a “comparative advantage.” This theory effectively condemns late-industrializing countries like Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China to become the hinterlands of industrialized countries: they would export raw materials and lightly processed goods and import manufactured goods. The bulk of the value-added, and the bulk of the incomes, would be generated elsewhere. Successful late-industrializing countries have all rebelled against this prospect, choosing instead to alter their comparative advantage through heavy investment. This investment has to be co-ordinated (for reasons discussed below), so the governments of these countries have intervened directly in the allocation of investment. This level of intervention is only possible if the government has almost dictatorial authority — as has been the case with many successful late-industrializing countries. Japan grew rapidly under the influence of a powerful national bureaucracy, Korea and Taiwan under military rule, China under an authoritarian one-party system.

The western ideal of free markets and democratic government has been successful at continuously renovating advanced economies. It has been less successful when the economy needed to be torn down and rebuilt on stronger foundations.

Timing is Everything

World trade expanded rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1954, global exports were twice what they had been in 1913; in 1976, they were ten times greater.26 This expansion aligned with Korea’s early industrialization, allowing Korean manufacturers to more easily find foreign markets for their goods. Korea’s industrialization also occurred during a period when GATT’s trade rules were particularly favourable to developing countries:

Korea implemented industrial policy while exporting to the rest of the world, mainly to advanced countries. Industrial policy thus needed an asymmetric trade relationship whereby the country could export freely while protecting and subsidizing domestic industries. In the 1960s and 1970s, advanced countries allowed such asymmetric relationships under the GATT system, which had the built-in infant industry clause. It was an exception in history: advanced countries had never allowed such a relationship with developing countries before the Second World War, and it would be discontinued from the mid-1980s.27

Korea’s early manufactures were mostly labour-intensive goods produced by low-wage workers. There was little competition in the markets for these goods because most low-wage countries chose to follow import-substitution strategies. There was more competition a decade or two later, as countries like Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia began to contest world markets — but by then, Korea was “moving up the value chain,” shifting to the production of goods that required heavy capital investment, technological sophistication, and skilled labour.

The Chaebols

Park’s economic policies were even more interventionist than Rhee’s policies had been. Their success depended upon the co-operation of the business groups known as chaebols.

A chaebol is a family-owned, heavily diversified conglomerate. It is similar to Japan’s zaibatsu, with the exception that the Japanese conglomerate generally included a bank, allowing it to internally finance its own expansion. The Korean banks were state-owned until the late 1950s, so the early chaebols did not own banks. They could raise some capital internally, but still required reliable access to credit markets, which gave the government a great deal of leverage.

Very few chaebols developed under Japanese rule. (Among these few were Samsung and Lucky-Goldstar, now known as LG.) The chaebols became more prominent during and after Rhee’s presidency.

Most of the chaebol existed as firms by the immediate postwar period, but they were small enterprises milling rice or repairing automobiles. Daewoo did not even appear until the late 1960s. The others did not grow into anything big until the 1970s…The characteristic of the big chaebol groups is their concentration in heavy manufacturing, meaning that they could not exist before the “deepening” of the early 1970s.28

The diversification of the chaebols in the 1950s and 1960s stemmed from two factors. The first was that experienced entrepreneurship was a scarce factor of production. A successful organization could exploit its entrepreneurial advantage by branching out in new directions. The second was that the thinness of Korean manufacturing meant that chaebols sometimes found that there were no domestic producers of the intermediate goods that they needed. They could obtain these goods internationally, but often preferred to set up their own production facilities. The evolution of Lucky-Goldstar, as described by its chairman in 1985, illustrates both of these factors.

My father and I started a cosmetic cream factory in the late 1940s. At the time, no company could supply us with plastic caps of adequate quality for cream jars, so we had to start a plastic business. Plastic caps alone were not sufficient to run the plastic-molding plant, so we added combs, toothbrushes, and soap boxes. This plastics business also led us to manufacture electrical and electronic products and telecommunication equipment. The plastics business also took us into oil refining which needed a tanker-shipping company. The oil-refining company alone was paying an insurance premium amounting to more than half the total revenue of the then largest insurance company in Korea. Thus, an insurance company was started. This natural step-by step evolution through related businesses resulted in the Lucky-Goldstar group as we see it today.29

The chaebols’ willingness to pursue profit wherever it might be found led to some extreme transformations. Hyundai, one of the world’s leading automobile manufacturers, began as a cement company.

Corruption was one of the main concerns of the military junta led by Park, and shortly after it took power, it began to investigate corruption in political parties, government bureaucracies, and even the military itself. The chaebols were not immune from its scrutiny.

Two weeks after the coup, thirteen major businessmen were arrested. Although eight of these were induced to make large “contributions” to the government and were released, the investigation was broadened to include another hundred and twenty businessmen. The definition of “illicit” wealth covered the entire range of rent-seeking and rent-granting activities that had been pervasive, if not unavoidable, under Rhee: illegal contributions to political funds; illicit purchase of vested properties; profiteering from preferential access to government contracts and loans; and misallocation of foreign funds.

Though the government seized all outstanding shares of commercial bank stocks, thus gaining control of a powerful policy instrument, it compromised with large manufacturing and construction firms. In August 1961, the final decision of the investigation committee demanded that thirty entrepreneurs refund an amount that was much lower than the initial estimates of illegally accumulated wealth. The reason for this shift in policy is summarized neatly by Kim Kyong-dong: “The only viable economic force happened to be the target group of leading entrepreneurial talents with their singular advantage of organization, personnel, facilities and capital resources.”30

The alliance between Park’s government and the chaebols was forged out of this realization. The released businessmen formed the Association of Korean Businessmen.

The members of the newly formed Association submitted a plan to the [junta’s] Supreme Council identifying fourteen key industrial plants, including cement, steel, and fertilizer in which they were interested in investing if the appropriate supportive policies were forthcoming. The penalties imposed for the illicit accumulation of wealth were to be invested in new plants, but these totalled less than one-sixth of the cost of the Association’s plan.31

The Economics of General Park

Park came to power without a concrete plan for economic development, and without an analytical framework on which to build one. There is no evidence that he ever thought about comparative advantage. The only western ideas that might have influenced him were those of Friedrich List, who argued that what a country produced is more important than what it consumed, and that protectionist measures were useful developmental tools. But it is more likely that Park’s economic thinking was determined by his own background and his awareness of East Asian history. He was a military man, which predisposed him to top-down command structures. He was aware of the deliberateness with which Japan had restructured its own economy, and had seen the same deliberateness successfully applied to Japan’s exploitation of Korea and Japanese-occupied Manchuria.

Nevertheless, an after-the-fact understanding of Park’s economic policies can be expressed in western economic concepts. First, Park was deliberately altering Korea’s comparative advantage, accepting heavy short-term costs in the expectation of long-term gains. Second, this manipulation required the intervention of the national government — it would not have been undertaken by private firms acting in their own interests. There are two issues here: co-ordination problems and economies of scale.

The co-ordination problem arises when some entrepreneurs cannot move their projects forward unless other entrepreneurs move theirs forward. Consider two entrepreneurs contemplating investments in different production facilities. The first entrepreneur requires an intermediate good that would be produced in the second entrepreneur’s facility, and won’t proceed until he knows that the second entrepreneur is going ahead with his investment. Meanwhile, the second entrepreneur’s facility won’t be profitable unless there is strong demand for its output, so he won’t proceed until he knows that the first entrepreneur is going ahead with his investment. Neither entrepreneur is willing to invest before the other one, so neither invests.32 For Park, the solution to the thinness of markets — which is what gives rise to the problem — was for the government to exert considerable control over the allocation of investment.

Some capital-intensive industries, such as steel and shipbuilding, are characterized by increasing returns to scale. In these industries, a firm’s average cost of production goes down as its output goes up, so only very large firms are able to produce goods cheaply enough to compete on world markets. A Korean entrepreneur, acting alone, might be unwilling to undertake the investment required to achieve this scale of production. He would likely be forced to finance at least part of his investment by borrowing abroad, thereby exposing himself to the risk of adverse movements in interest rates or exchange rates. And if his firm is highly indebted, these movements could lead to bankruptcy. The smallness of Korea’s domestic market would force him to sell much of his output abroad, so he would also incur the risk of foreign business fluctuations. Since his firm and the quality of his goods would not be well known abroad, he would initially have difficulty making foreign sales. For Park, the solution to the problem of scale was to share the risks across society through such policies as preferred access to domestic credit or loan guarantees for foreign loans. He consistently encouraged (for better or for worse) firms to build bigger, looking beyond the short-term hurdles to long-term competitiveness.

Investment

Park’s government placed a heavy emphasis on the development of Korea’s commercial infrastructure.

The government not only assumed the role of investor by itself but also provided the private sector with tax incentives and preferential public loans to build infrastructure, such as railroads, turnpikes, and power plants. The government also built industrial complexes for the collective accommodation of related industrial plants, thereby addressing the coordination failure of the market. Notably, the government built the Ulsan Industrial Complex in 1962, the first of such projects, followed by the construction of other complexes later.33

Tax instruments and government loans were sufficient for this purpose. However, the government also exerted extensive control over the sectoral allocation of investment in the private sector. Its instrument in this case was its almost complete control over investment funding.

Korea’s savings rate was very low, which had two immediate implications. The first was that the financial markets were not deep, making it difficult for private firms to obtain investment funds by issuing bonds or equity. Firms were instead forced to rely primarily on loans from the newly nationalized banks, whose policies were largely dictated by the government.34 The second implication was that the banks themselves were not well capitalized. They could not be the vehicle of rapid economic expansion without the assistance of the government. This assistance came in the form of central bank “discounting.” A commercial bank that had issued an investment loan could — under certain conditions — use it as collateral to obtain a loan from the central bank at a preferred rate of interest. These loans kept the commercial banks solvent. The government’s control over the conditions under which they were given gave it control over the allocation of investment.

The government ensured that the interest rates charged by commercial banks were well below the interest rates charged in the unregulated or “curb” market. The interest rate difference was effectively a subsidy on investment. Other subsidies came in the form of tax reductions, deferrals and exemptions.

The cost of the government’s subsidies were partially borne by printing money, so the inflation rate stayed in the 10% to 25% range throughout Park’s rule. The commercial bank rate was well below the inflation rate for extended periods of time, so firms earned a profit (in real terms) simply by borrowing.35 Unsurprisingly, Korean firms were highly indebted, making them vulnerable to even small changes in market conditions. They often needed government bailouts.

The sectors that the government targeted for investment shifted over time, as indicated by the government’s five year plans. (The term “five year plan” is usually associated with central planning, but the Korean plans were merely informational, showing the direction of government policy.)

The First Five-Year Economic Development Plan (1962–1966) announced by Park’s junta emphasized the import substitution of industries such as cement, fertilizer, petroleum refining, chemicals, and synthetic textiles, which were relatively higher-technology industries at that time…Industrial policy continued in the Second Five-Year Economic Development Plan (1967–1971). The government promoted seven industries — machinery, shipbuilding, textiles, electronics, petrochemicals, iron and steel, and nonferrous metal — by promulgating promotional laws for each of them. Then, in 1973, the government launched the “Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive” (henceforth HCI drive), a comprehensive plan to promote six industries: iron and steel, nonferrous metal, machinery, electronics, shipbuilding, and chemicals. After pushing the HCI drive hard for six years, the government began to scale it down in April 1979.36

The government didn’t just allocate investment across sectors: it often allocated it to particular firms within a sector. The government’s preferences were sometimes pure favouritism — pure cronyism — but over time, the government began to push forward firms with a history of success and push aside firms that had failed. It also increasingly relied on powerful chaebols to advance government policy. The chaebols were so reliant on government favour that a government request was effectively an order.

A salient example was Hyundai’s entry into shipbuilding. Park Chung Hee urged Chung Ju-yung, the founder of Hyundai chaebol, whose main business was construction, to enter the industry. When Park heard the news that no international finance could be found for the Hyundai shipyard, and the project would have to be abandoned, his response was a thinly veiled threat: “If you only want to do what’s easy, then you’ll get no more help from us.”37

Exports and Enforcement

A government’s conscious restructuring of an economy is known as industrial policy. Alice Amsden argues that what made Korea’s industrial policy unique — and successful — was its emphasis on enforcement. Many countries subsidized firms in favoured industries, but only Korea set out clear performance standards and punished firms that failed to meet them. Korean subsidies weren’t simply giveaways. They were part of an implicit but well-understood contract, and failure to fulfil it would have consequences.

One aspect of this approach was a willingness to push out firms that it viewed as insufficiently successful. Park’s government refused to

… bail out relatively large scale, badly managed, bankrupt firms in otherwise healthy industries. The bail-out process has been highly politicized insofar as the government has typically chosen close friends to do the taking over of troubled enterprises (the production facilities of troubled enterprises are never allowed to rot). This corruption notwithstanding, when the victim of bankruptcy has appeared to be poorly managed, the government has deserted it…For example, a company named Shinjin had a larger market share in the Korean automobile industry in the 1960s than Hyundai Motors. Shinjin’s owner, however, could not survive competition from Hyundai’s “Pony” and the oil shock in the 1970s. The company went bankrupt and the government, as banker, transferred Shinjin’s holdings to Daewoo Motors.38

The government also acted proactively, limiting entry into new industries to ensure that firms could realize scale economies.

The most visible aspect of this approach was export targets. Exports were valuable to Korea for a number of reasons. They provided the foreign exchange needed to purchase capital goods abroad. (American aid had been a major source of foreign exchange, but was now winding down.) They absorbed some of the goods produced by the large facilities favoured by Park. Exports also forced Korean firms to adjust to foreign preferences, meet international quality standards, and adopt modern technologies. Indeed, exports were so central to Korea’s economic success that they become one of the government’s central preoccupations.

The Park government employed non-price measures to promote exports. The first of them was the Monthly Export Promotion Conference, later renamed the Monthly Trade Promotion Conference, presided over by the president himself, which brought the public and private sectors together and served to disseminate the government’s emphasis on export promotion and quickly resolve problems encountered by exporters through the final decision of the president. The second was the export targeting system, under which the government set annual export targets by major commodity groups and destination and assigned quotas to individual firms; the government then monitored the export performance of those firms against the quotas. It worked because the government set quotas considering the economic conditions, but also because firms recognized meeting the quotas as instrumental in maintaining goodwill with the government.39

A firm that failed to meet its export targets could lose its access to loans, or have its tax returns scrutinized, or experience delays in dealing with the bureaucracy. It would not be a candidate for expansion into a new industry.

The government could be supportive as well as punitive. Many of Korea’s entrepreneurs had little international experience, so export promotion was challenging for them. Sometimes their exports were not initially profitable. The government supported them by imposing import tariffs on goods that it struggled to export. The tariffs raised the domestic price, so that excess profits earned on the domestic market could offset the losses incurred abroad. A big assist to exporters came in 1965, in the form of a 50% devaluation of the Korean won.

Technology

Korea’s restructuring involved a shift from labour-intensive production to capital-intensive production, and a shift from simple technologies to complex technologies. Park intended to make these transitions in double time.

Korean firms recognized the need to import technologies from abroad but resisted any hint of foreign domination.

Massive imports of foreign licenses and assistance have been viewed as a means to attain technological independence, and thus as part of a larger effort, in both the public and private spheres, to avoid foreign control. Industrialization has occurred almost exclusively on the basis of nationally owned rather than foreign owned enterprise. Foreign technical assistance has been purchased in preference to depending on foreigners to run Korean plants. Whether in Korea’s shipyards, steel mills, machinery works, automobile plants, or electronics factories, the credo has become, “Invest now in in-house technological capability — even if outside expertise is cheaper — to reap the rewards of self reliance later.”40

This approach to technology was costly to Korea. Modern technologies are rarely plug and play; instead, they contain elements that are “tacit and not explicitly codified in designs and blueprints.”41 The costs of learning how to adapt and use new technologies frequently included the cost of failing and beginning again. New technologies also highlighted the need for backward and forward linkages. Hyundai’s entry into shipbuilding illustrates these factors.

The company started out by importing its basic design from a Scottish firm, but soon found that this was not working out. The Scottish design relied on building the ship in two halves because the original manufacturer had only enough capacity to build half a ship at a time. When Hyundai followed the same course, it found out that the two halves did not quite fit. Subsequent designs imported from European consulting firms also had problems, in that the firms would not guarantee the rated capacity, leading to costly delays. Engines were available from Japanese suppliers, but apparently only at a price higher than that obtained by Japanese shipyards. Moreover, ship buyers would often require design modifications, which Hyundai would be unable to undertake in the absence of an in-house design capability. Only with large enough capacity would it pay for Hyundai to integrate backwards (into design and engine building)…Scale in turn depended on having access to a steady and reliable customer (a merchant marine). The Korean government provided Hyundai with substantial assistance, as well as an implicit guarantee of markets. Hyundai eventually integrated both backwards and forwards. The government’s guarantee came in handy in 1975 when a shipping slump led to the cancellation of foreign orders. President Park responded by forcing Korean refiners to ship oil in Korean-owned tankers, creating a captive demand for Hyundai.42

An expanding network of linkages is probably responsible for the rising rate of profit in Korea’s manufacturing sector. The profit rate “steadily rose from 9% in 1951-3 to 16% in 1954-6, to 28% in 1957-62, and to 35% in 1963-70.”43

The Korean Economy after General Park

The figure below shows Korea’s GDP per capita. The vertical scale is logarithmic, so the growth rate is proportional to the slope — a flattening of the slope indicates a fall in the rate of growth. Korea’s growth continued unabated after Park was assassinated in 1979. The first setback was the Asian financial crisis of 1997. The heavily indebted chaebols were hit particularly hard — more than half of the largest chaebols went bankrupt. Korea recovered from the crisis quickly, but its growth after the crisis was slower than its growth before the crisis.

Korean economic policy was forced to change significantly in the 1980s. The United States, Korea’s most important export model, had been allowing certain countries to trade “asymmetrically,” protecting their own domestic industry while selling in the American market without impediment. The United States now became impatient with this practice.

The United States had allowed its asymmetric relationships with Europe and Japan on a temporary basis until they recovered from the devastation caused by the Second World War. As the temporary circumstances ended with their recovery, the United States returned to the original principle of the GATT to look for reciprocity. Japan became a major target in the move, but South Korea was perceived as “a Second Japan.”44

The Korean government responded with a dramatic reduction in tariff protection.

The government cut protection across-the-board. From 1981 to 1995, average statutory tariffs declined from 34.4 percent to 9.8 percent, while the import liberalization from quantitative restrictions rose from 60.7 percent to 92.0 percent…By the early 1990s, its subsidies to the manufacturing industries were 2.8 percent of the manufacturing value added, not far above the OECD average of 2.5 percent.45

Then, in 1986, the Korean government announced that its industrial policy would no longer favour particular sectors of the economy. One aspect of the new policy was to adjust the country’s education policy, shifting its emphasis toward science and engineering. Another aspect was the advancement of research and development.

The government granted tax deductions and exemptions and preferential loans to encourage R&D efforts. It also established many research institutes in specific fields, in addition to those established in the 1960s and 1970s. The changing government policy coincided with the changing competitive strategy of firms. Firms – particularly chaebol firms – paid more attention to R&D efforts as they recognized that foreigners were less and less willing to provide technology while the South Korean wage level was rising. Firms began to establish in-house R&D institutes. Government research institutes and firms’ in-house R&D institutes were emerging as two major pillars of R&D efforts. The government built science parks to accommodate government research institutes and firms’ in-house R&D institutes. They often collaborated with each other in developing technology.46

Korea’s goal in earlier decades was to raise its technology to the level of the most advanced countries. By the 1980s it had achieved that goal in certain areas. The mass distribution of IBM’s first personal computer began in 1981; the mass distribution of Samsung’s first personal computer began in 1983. Korea was on its way to being a technological leader rather than a follower.

- Myung Soo Cha, “The Economic History of Korea,” EH.net ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, pp. 22-3. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 22. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 23. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 24. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 30. The Great Depression, which began in 1928, caused many countries to protect their industry by enacting measures that discouraged and penalized imports. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 35. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 33. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 31. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, pp. 59-60. ↩

- Alice Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (Oxford, 1989), p. 39. ↩

- Rhee, quoted by Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 56. ↩

- Rhee, writing to Eisenhower. Quoted by Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 56. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 64. ↩

- Suppose that the growth rate of the manufacturing sector rises by 5 percentage points. If manufacturing is 50% of GDP, the growth rate of GDP rises by 2.5 percentage points. If it is only 10% of GDP, the growth rate of GDP rises by only 0.5 percentage points. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 71. ↩

- South Korea’s savings amounted to only about 4% of GNP during the late 1950s, and GNP was itself a small number. Since very little investment could be financed out of savings, most firms were undercapitalized. Instead, they were debt financed, which meant that access to the credit markets was crucially important, the difference between solvency and bankruptcy. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 67. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 67. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 83. ↩

- The data are from the Penn World Table, version 10.1, and can be downloaded here. ↩

- Dani Rodrik, “King Kong Meets Godzilla: The World Bank and The East Asian Miracle,” CEPR Discussion Paper (1994). ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, pp. 65-6. ↩

- Rodrik, “King Kong Meets Godzilla,” p. 9. ↩

- 1945 and 1970: Andrea Savada and William Shaw, eds., South Korea: A Country Study (Library of Congress, 1990), p. 115. 1960: Rodrik, “King Kong Meets Godzilla,” Table 1. ↩

- Data from Our World in Data. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 163. ↩

- Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift, p. 15. ↩

- Quoted in Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant, p. 126. ↩

- Stephan Haggard, Byung-kook Kim and Chung-in Moon, “The Transition to Export-led Growth in South Korea,” Journal of Asian Studies (1991), pp. 858-9. ↩

- Stephan Haggard, Byung-kook Kim and Chung-in Moon, “The Transition to Export-led Growth in South Korea,” p. 859. ↩

- It might be argued that this problem is solved by trade: the first entrepreneur invests and buys the intermediate good abroad if he can’t buy it domestically; the second entrepreneur invests and sells his output abroad if he can’t sell it at home. The outcome is that they both invest, allowing the first entrepreneur to buy from the second. The problem with this argument is that it assumes that trade functions smoothly — it doesn’t now, and it certainly didn’t before the internet and container ships reduced communication costs and transport costs. As well as these explicit costs, Korean firms would have faced information costs: overseas firms knew very little about the reliability of Korean firms or the quality of Korean goods. Finally, production processes were much less flexible than they are now — which is probably why Lucky-Goldstar ended up producing plastic caps themselves instead of buying them abroad. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 96. ↩

- They could also obtain loans from unregulated lenders known collectively as the “curb market,” but the interest rates were substantially higher. Firms could also attempt to borrow abroad, and when they did so, the government typically guaranteed their loans. On the other hand, foreign direct investment and foreign purchases of equity were discouraged: Korean firms were to be Korean owned. ↩

- See, for example, Table 6.6 in Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, pp. 161-2. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 172. ↩

- Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant, p. 15. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 108. ↩

- Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant, pp. 21-2. ↩

- Dani Rodrik, “Getting Interventions Right: How South Korea and Taiwan Grew Rich,” Economic Policy (1995), p. 81. ↩

- Rodrik, “Getting Interventions Right,” p. 82. ↩

- Rodrik, “Getting Interventions Right,” p. 83. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 179. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 180. ↩

- Jaymin Lee, The Tortuous Path of South Korean Economic Development, p. 182. ↩