Based on Gary Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History (Routledge, 2003), Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-75 (Stanford University Press, 1982), and Richard Katz, Japan: The System that Soured (Routledge, 1998)

World War II had a devastating impact on Japan. Its soldiers died in savage battles and its civilians in relentless bombing raids; its people narrowly avoided starvation during the first year of peace. Japan’s cities and factories were decimated. Its GDP per capita was 42% lower in 1946 than in 1939.1 And yet Japan — like Germany, its former ally — recovered relatively quickly. By the mid-1950s, Japan was as economically successful as it had been before the war.

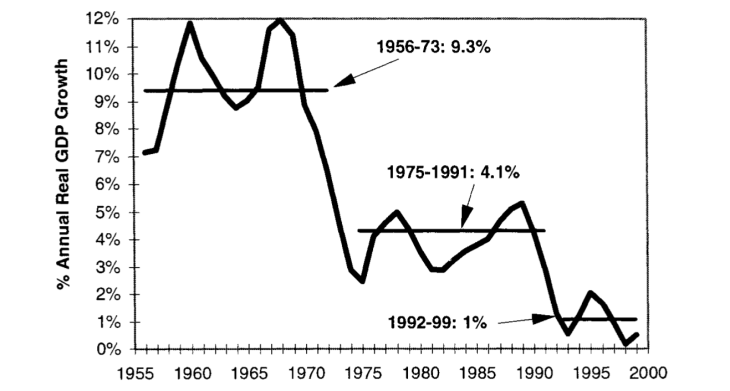

Japan’s growth did not end with recovery. It continued unabated until 1973, when Japan’s GDP per capita matched those of leading economies such as Germany and the United Kingdom. Japan grew more slowly over the next decade or so, but still grew more rapidly than either Germany or the United Kingdom. It was widely believed that Japan’s world-beating growth would continue, that its unique economic institutions would allow it to displace the United States as the world’s leading economy. This belief proved to be illusory. In the late 1980s the mismatch between the perception and the reality of Japan’s growth led to a bubble in the prices of Japanese real estate and equities. The bubble burst in 1992, the government resisted reform, and the economy stagnated for a decade. Japan subsequently returned to the kind of slow and steady growth experienced by other well-developed economies such as Italy and the United Kingdom, but its dreams of economic dominance had vanished.

Japan before the War

The first few years after the war were years of recovery and transformation, but what was Japan recovering to and transforming from?

Japan had consciously and deliberately begun to industrialize after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. By the end of World War I, manufacturing accounted for 28% of Japan’s national output, and manufacturing and services jointly accounted for 62% of output.2 Japan nevertheless continued to be relatively poor. Its output per capita was about three-quarters of that of Italy throughout the 1920s, and comparable to those of late-industrializing countries such as Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

Japanese society was hierarchical. At the top of the hierarchy was the emperor, the quasi-divine “father” of the Japanese people. The emperor ruled the country and was extremely wealthy. Below the emperor was an aristocracy consisting of hereditary court aristocrats, descendants of the Tokugawa-era daimyo (given aristocratic titles in 1884), and “men who had demonstrated their merit.” The aristocracy encompassed about 1000 families; it “exercised a near monopoly over status, wealth, and power.”3

At the bottom of the rural hierarchy were landless or nearly landless tenant farmers who were both powerless and impoverished.

High levels of household debt, the sale of daughters into prostitution, widespread malnutrition and disease, high rates of infant mortality, the small stature of army recruits from rural areas, and the very low level of discretionary purchases all underscore the deprivation that plagued millions of poor, rural families. It is not surprising that the average life expectancy at birth for males during the early 1930s was about forty-six.4

Their urban counterparts held a range of basic jobs in manufacturing, construction, transportation, and trade. The lowest of the low were the burakumin, outcasts who did work that was judged to be unclean, such as butchering and tanning.

There were many gradations of status between these extremes. Old wealth had high status, as did the new wealth of the industrialists. Professionals also held high status. Below them, the white-collar workers from the civil service, banks, trading companies, and hospitals constituted a new and expanding middle class. And below them were the shopkeepers and craftsmen who embraced “diligence, frugality, and upward striving.”5

Japanese businesses displayed an equal diversity. Some businesses operated large and modern factories, with thousands of well-paid workers organized and supervised by engineers and professional managers. Many more businesses “relied on low-skilled, poorly paid workers using simple tools under the direction of self-trained owner-managers.” Between these two extremes were factories that

… combined features of both the large and small firms. Some used advanced technology in small plants employing a few hundred workers to make specialized components for a final producer. This kind of subcontractor was especially common in new industries making aircraft, machine tools, and electric products. There were other small firms with a few score workers who used simple, manual techniques to make low-cost items for domestic or external markets. And there were literally thousands of tiny establishments with only two or three workers. They provided craft items and processed foods that consumers needed on a regular basis, such as pots and pans, door panels and floor mats, and bean curd and condiments. The small and the medium-sized firms…satisfied almost all domestic demand for household goods, food products, and most other daily necessities.6

The most powerful enterprises were the zaibatsu, which had been formed at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The zaibatsu were all owned by a family or a family group that exercised its financial control through a holding company. A zaibatsu usually consisted of about ten interlinked firms that ordinarily included a bank, an international trading firm, a real estate entity, an insurance company, several manufacturing firms, and a mining company. Ownership by the holding company, interlocking directorships, and cross-holding of shares provided the means for coordinating these diverse enterprises under the managerial supervision of the holding company. Zaibatsu formed in part to insulate themselves from the volatility of prewar Japanese capital markets by generating their capital internally. In this way the zaibatsu achieved a high degree of autonomy, which they used to pursue a coordinated strategy of expansion and innovation.7

Japan’s government was unsettled. There was a well-understood gap between principle and practice, and during the 1930s, there was an unstoppable shift toward militarism.

The catalyst for the Meiji Restoration had been the “unequal treaties” (formally, the Ansei Treaties) imposed upon Japan by the West. The new regime, seeking to raise its standing with the West and cast off the unequal treaties, enacted a constitution that merged European and Japanese institutions.

The emperor exercised all legislative, executive, and judicial powers. Theoretically, his authority was supreme. In practice, he had to delegate his powers to loyal public servants whom he appointed to carry out his will. The formal structure of national government laid out in the constitution consisted of an advisory privy council, a cabinet and a prime minister, a bicameral legislature, a judiciary with limited powers of constitutional review, and a military with substantial autonomy. In addition, a carefully selected body of national civil servants — the bureaucracy — emerged to administer the day-to-day affairs of state.8

Although the apparatus of government suggested democracy, the emperor remained firmly in control.

Constitutional government did not mean the existence of parliamentary democracy, cabinets responsible to the Diet [Japan’s legislature], or a titular head of state. The cabinet and the armed forces were responsible to the emperor and to him alone. Cabinets were “transcendental” and non-party, appointed by the emperor not necessarily from the majority party in the Diet. Important government decisions had in turn to be ratified by the non-elective Privy Council. The leaders of the armed forces had direct access to the emperor and complete autonomy from the cabinet regarding defence matters.9

The upper house of the Diet was dominated by Japan’s traditional elite, and cabinet ministers and Privy Council members were drawn from the same elite. The elite also had access to the emperor through informal channels.

If there was a challenge to the power of the elite, it came from the bureaucracy and not from the political parties.

In seeking to forestall competitive claims to their own power by the leaders of the [newly formed] political parties, the Meiji oligarchs created a weak parliament and also sought to counterbalance it with a bureaucracy they believed they could staff with their own supporters, or at least keep under their personal control. But over time, with the bureaucracy installed at the center of government and with the passing of the oligarchs, it was the bureaucrats — both military and civilian — who arrogated more and more power to themselves.

The political parties…suffered from the weakness of having arrived second on the political scene. The bureaucracy claimed to speak for the national interest and characterized the parties as speaking only for local or particular interests. As Japan industrialized, the parties slowly gained clout as representatives of zaibatsu and other properties interests, but they never developed a mass base.10

The bureaucracy played a pivotal role in the development of the Japanese economy. The bureaucrats believed that restraints on competition would help to build large corporations that could be internationally competitive. One aspect of this policy was the legalization and endorsement of producer cartels. A law enacted in 1925 gave “export associations” the right to set export prices for their members, and a second law gave the members of an association the right to make agreements that set out each member’s production quota. A broader law was enacted in 1931: it legalized “treaty-like cartel agreements among enterprises to fix levels of production, establish prices, limit new entrants into an industry, and control marketing for a particular industry.”11 Cartels were formed in 26 major industries, including silk thread, rayon, iron and steel, and coal.

The most striking feature of Japanese government was that there were so many ways in which power could be exercised and so few ways in which it could be restrained.

No single element within the constitutional order, either formal or informal, exercised a decisive influence…Rather, the occupants of the various sites of power struggled among themselves for ascendancy. The aristocracy pursued its interests through one body of the legislature, the House of Peers, and, on occasion, through direct service in the cabinet or on advisory bodies. The military exercised its influence within the government through two seats on the cabinet and through private audiences with the emperor conducted by the leaders of its general staff. Elected politicians relied on the other body of the legislature, the House of Representatives, and on the cabinet as their forums of influence, as did members of big business. And the national civil servants in the bureaucracy, although often competing among themselves, strove to impose some measure of coherence and integration on national policy.12

No-one, not even the emperor, was able to harness and co-ordinate the competing factions. The occupation of Manchuria, for example, was undertaken by an army that insisted upon its constitutional “right of supreme command,” and the government was left to sort out the consequences of an occupation that it had neither sought nor sanctioned. The co-ordination of power was the central problem of Japanese governance from the occupation of Manchuria in 1931 to war’s end in 1945.13

The General Staff of the Japanese Navy foretold the course of an offensive war in 1940:

A Japanese invasion of Indo-China would provoke an American oil blockade, which would force Japan to seize the Dutch East Indies, which would in turn lead to war with America. If such a war lasted more than a year, Japan would run out of resources and America would win.14

But the momentum of war could not be halted. The Navy’s prophecy became Japan’s script.

The Occupation

The atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima destroyed these cities so completely that the number of dead cannot be reliably estimated — it could be as high as 200,000. These bombings had been preceded by a fourteen-month conventional bombing campaign during which thousands of people, sometimes tens of thousands, were killed in every raid. Cumulatively, the conventional bombings killed more people than the atomic bombings.

Incendiary bombs had been used to produce firestorms in communities that were largely built of wood, straw and paper. Some smaller factory towns were entirely incinerated, while larger cities became uninhabitable.

Japanese used the term yaki-nohara, or burned plain, to describe their cities. That is how they looked in August 1945. They were vast expanses of charred ruins. In many areas, as far as the eye could see, what were once thriving commercial districts, quiet residential neighborhoods, and bustling factory zones were burnt rubble.15

The bombings destroyed more than half of Yokohama and Kobe, and more than a third of Tokyo and Osaka.16

Altogether, the war destroyed 25% of Japan’s buildings, 34% of its industrial machinery, 80% of its shipping capacity, 10% of its railway system, and 10% of its gas and electricity infrastructure.17 The war’s destruction, coupled with the breakdown of the market system, led to extreme food shortages — a “prison of hunger.”18

After Japan’s surrender to the Allied powers, the country was placed under the administration of the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers (SCAP), an almost entirely American organization. SCAP’s goal was to prevent further Japanese military aggression.

Japan was disarmed. It was required to adopt a new constitution that eliminated the competing channels of power. The emperor was stripped of his governmental powers, the prime minister and his cabinet acquired all executive authority, both houses of the Diet were made elected bodies, and the authority of the Supreme Court was broadened. Politicians and business leaders who were deemed to have been complicit in the war were purged.

SCAP reformed the economy in significant ways. It redistributed more than a third of Japan’s agricultural land, transferring it from landlords to landless or nearly landless farmers. Tenant farmers had worked half of the agricultural land before redistribution; they worked only a tenth of it after redistribution.19 This reform raised farm productivity, reduced rural poverty, and greatly increased the number of Japanese who had a stake in their country’s future. SCAP also gave workers the right to organize themselves into unions and to strike — both of these activities had been illegal before 1945.

SCAP substantially reduced the concentration of economic power.

Officials confiscated the stock holdings of fifty-six members of fourteen leading zaibatsu families; they also confiscated the stocks and bonds belonging to major zaibatsu holding companies. These shares were then sold on the open market, often to individual buyers. Reformers also eliminated the holding companies themselves, thereby destroying the managerial nerve center of the zaibatsu enterprises. To further reduce the concentration of zaibatsu influence, the reformers ordered large firms, such as the Mitsui Trading Company and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, to be divided into smaller and less influential parts. Finally, to protect against reconsolidation of power, Allied authorities persuaded the Diet to institute antimonopoly laws and the Fair Trade Commission to oversee them. These laws prohibited interlocking directorships and the kind of internal coordination that had shaped the zaibatsu during the prewar era.20

This initiative was not popular among the Japanese, and the antimonopoly laws were relaxed as soon as the occupation ended. Export cartels were exempted from the antimonopoly laws in 1952, and recession and rationalization cartels were likewise exempted in 1953.21

SCAP’s intention was to leave Japan with a functioning democratic government, so it chose to work through the government rather than displace it. The bureaucrats were not purged because SCAP considered them to be an essential part of the governmental system, and because it mistakenly believed them to be apolitical. This decision strongly influenced Japan’s postwar economic policy. The bureaucrats who had chosen to constrain competition before the war were in complete control of the economic ministries after the war. They reported to the prime minister and his cabinet who, under the new constitution, held sole executive authority and controlled the flow of legislation through the Diet. In the American lingo of the time, the bureaucrats were “sitting in the catbird seat.”

Industrial Policy

From an economic perspective, the years immediately following the war were Japan’s bleakest.

Vast stretches of urban areas were flattened, and a significant share of the nation’s ports and factories were inoperative. Millions of people had been forced back to the countryside, so rural villages were crowded and underproductive. Transportation systems were ruined, decrepit, or outmoded, and investment capital was scarce. The lack of a merchant marine closed Japan off from export markets and complicated imports of needed materials…

Allied policies prevented Japan from addressing many of these problems during the several years that Washington was determined to…ensure that Japan not wage war again. This meant prohibitions on rebuilding heavy industry and continued isolation from international markets. Moreover, such reform policies as zaibatsu dissolution actually complicated recovery. They dispersed capital, diminished economies of scale, and undercut managerial control. The purge also removed influential business figures, whose departures harmed individual firms and the economy as a whole.22

SCAP began to shift away from punitive policies and towards more conciliatory ones as early as 1948. The American government was concerned by the growing strength of communism in Europe and China. It began to see Japan as democracy’s foothold in Asia, a role for which it would need to be economically strong. The dissolution of the zaibatsu was paused; other restrictions were abandoned. The Korean War, which began in 1950, provided further support for the Japanese economy.

Partly out of necessity and partly out of design, the United States opted to rely on Japanese suppliers for many wartime needs. These purchases stimulated demand in such key industries as textiles, chemicals, vehicles, steel, and coal mining. Firms that geared up to meet war orders made quick profits, which they reinvested in new factories. Under this stimulus, the industrial sector finally enjoyed a resurgence.23

The Japanese were independently attempting to reassemble their shattered economy. Japan had idle industrial capacity and an underutilized labour force after the war. It needed energy and raw materials to put these resources to work. Coal was the primary energy source for industry and transportation, but coal production had collapsed at the end of the war.24 There was a severe shortage of imported raw materials owing to several factors: the scarcity of foreign exchange (due to the precipitous fall in Japan’s exports), the wartime destruction of the merchant marine, and the severing of many prewar trading relationships. The bureaucrats’ “March thesis” warned of the economy’s dire state: “By March of 1947 the Japanese economy would no longer be producing anything due to an exhaustion of stockpiles, a lack of imports, and an acute coal shortage.”25 The government responded with the priority production system. Industries designated as priorities — including coal, steel, and fertilizer — would be supported to the near exclusion of less favoured industries. Japan would build outward from these core industries.

This practice of “picking winners and losers” is commonly called industrial policy, and would be an integral part of Japan’s postwar economic policy. Industrial policy was primarily implemented by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), but the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance (MOF) also had roles to play.

The scarcity of foreign exchange in the early postwar period gave MITI its most powerful tool. Firms that acquired foreign exchange had to sell it to MITI, and firms that wanted foreign exchange had to apply to MITI to purchase it. This system

… gave MITI discretionary power to grant or deny access to resources vital to nearly all Japanese industries in the early postwar period: raw materials, foreign technology, and foreign markets. Denial of direct access to these resources by MITI meant that a firm could not survive as a fully independent enterprise.26

MITI tended to channel foreign exchange toward large firms, as these firms were believed to be more able to compete with foreign firms. MITI also had the right to approve or deny the importation of foreign technology, and again, its decisions favoured large firms.

MITI strongly supported large firms, but it also protected firms in “infant industries” from well-established foreign competitors. In the late 1950s, for example, MITI blocked a joint venture between Singer Sewing Machines and a Japanese company so that an indigenous industry could develop. Somewhat later, it prevented IBM from producing computers within Japan, instead requiring it to license its patents to Japanese firms. MITI ensured the growth of Japan’s nascent auto industry by strictly limiting the amount of foreign exchange that could be used to purchase foreign vehicles.

Japan’s financial policies favoured large firms over small ones.

Implemented primarily through the Bank of Japan and the MOF, financial policies were intended to keep the costs of capital low so that the largest and most productive firms could expand rapidly. Smaller firms that were less efficient producers were obliged to pay higher costs for their capital. The MOF established controls over corporate financing that restricted the growth of a corporate bond market, and it discouraged reliance on the stock market for corporate funds.27

The suppression of the bond and equity markets gave rise to the practice of “over-loaning,” further increasing the government’s hold on the economy.

Large enterprises obtain their capital through loans from the city banks, which are in turn over-loaned and therefore utterly dependent on the guarantees of the Bank of Japan, which is itself — after a fierce struggle in the 1950s that the bank lost — essentially an operating arm of the Ministry of Finance. 28

Over-loaning facilitated the rapid expansion of Japanese firms, but it also caused Japanese firms to be undercapitalized. In 1972 only 16% of the capital of Japanese corporations was owner capital.29

The centrality of debt finance gave rise to keiretsu, or “enterprise groups,” built around commercial banks.

As the fifties progressed, these banks began to assume the financial role that former zaibatsu holding companies had once played. They became the principal source of investment capital for the firms associated with them; they purchased more and more of the shares of those firms; and they came to play a guiding role in shaping the development of those groups…

In addition to the commercial bank situated at the hub, each keiretsu usually had two other financial institutions, an insurance company and a trust bank, that could provide loans or investment capital. Each also included one of the six large sogo shosha [trading companies], which served the marketing needs of group members. Most keiretsu had some exposure to the retail sector through a major department store…And each group had a variety of manufacturing concerns that offered it a presence in nearly every major industry: steel making, chemical production, electrical machinery, synthetic fibers, construction, shipbuilding, and food processing, to name the most important.30

The firms within the group held each other’s shares, minimizing the risk that they would be subject to unfriendly takeover bids, but also minimizing the ability of outside shareholders to influence their behaviour.

The uchiwa (“all in the family”) enterprise system also contributed to the insularity of management. Its essential elements were lifetime employment, the seniority wage system, and one-firm unions.31 As well, it “was customary for a firm’s managers to be chosen from among its long-time employees, who acted in accordance with what they saw as the long-term interests of the enterprise, which they viewed as a group of employees.”32

The interests of outside shareholders were downplayed, and the interests of employees were emphasized. As the economy expanded, managers pursued “long-term growth rather than short-term profits” and “were extremely concerned with market share.”33

The bankers were equally focussed on market share. With the Bank of Japan guaranteeing their investment loans, the bankers bore little downside risk when they expanded their loan portfolios. Excess manufacturing capacity and too much production — “excess competition” — was the unsurprising result.

As Japan’s exports rose, foreign exchange became less scarce and MITI became less able to control its allocation. MITI’s right to allocate foreign exchange was revoked in 1979, but by then it had become an ineffective policy instrument. Other controls (such as tariffs and import controls) were downplayed as Japan adjusted to GATT and OECD rules.34 MITI replaced all of these controls with “administrative guidance,” meaning its authority to “issue directives, requests, warnings, suggestions, and encouragements to the enterprises or clients within…[its] jurisdiction.”35 Administrative guidance did not have the force of law. Its power rested on the bureaucrats’ claim to represent the national interest, and on the firms’ willingness to accept the primacy of this interest.

Administrative guidance was used in the late 1960s to deal with excess competition, with MITI encouraging the creation of cartels that co-ordinated investment and production decisions. It was also used to deal with a problem created by the removal of capital controls. Japanese firms, having primarily used loans to fund their investment, had very low levels of capitalization, making them vulnerable to foreign takeovers. MITI promoted mergers — turning small and weak corporations into large and powerful ones — as a means of deterring such takeovers.

The Era of Rapid Growth

Japan’s GDP per capita grew at an average rate of 7.7% between 1948 and 1973.36 No other country had grown so fast for so long.

Japan’s willingness to compete on world markets was a large part of its success.

In the twenty years after 1953, the total volume of manufactured goods exported around the globe increased by six times, and the dollar value of world exports by more than seven. Old markets in Europe and North America expanded rapidly, and new markets arose in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Everyone seemed eager to trade.

Japan rode this wave of trade expansion as agilely as any other nation. Between 1955 and 1974, the dollar value of Japanese exports increased twenty-five times over. So did the value of its imports. Japan found itself poised to supply exactly what the world was demanding in greatest quantity: steel, fabricated metal products, ships, and precision equipment. Near the end of the era it added automobiles, business equipment, and audio and video appliances to this list. The sale of these exports earned the currency Japan needed to pay for its imports: petroleum and other energy sources, industrial raw materials, and food products. Despite having been almost shut off from the outside world in the early postwar years, Japan accounted for more than 6 percent of the world’s exports and an equal share of its imports by 1974.37

Japan’s growth required it to massively expand and modernize its capital stock. But the most basic rule of macroeconomics is that every unit of goods and services can be used for only one purpose. Businesses as a group can invest more only if either (a) households and governments use fewer goods and services, or (b) the net amount of goods and services sold abroad (exports less imports) is reduced. Japan chose option (a), consistently allocating a smaller fraction of its national output to consumption and government spending than did other countries at a similar stage of development.

The abolition of Japan’s armed forces, as required by the terms of surrender, eliminated a major component of government spending. As well, Japan’s social programs were not extensive. These factors allowed the government to set comparatively low tax rates. Firms retained more of their earnings, allowing them to internally finance much of their investment,38 and households retained more of their income.

The Japanese people were not prosperous during most of the postwar era. In the 1950s they had barely recovered from the effects of war.

For most families, the mid-fifties marked the return to a level of consumption many had not enjoyed since 1935. It was now possible to buy new shoes and new school uniforms for the children. Families could finally patch the roof and replace the moldy tatami (floor mats) as well. Major appliances were still out of reach for many. One struggling middle-class family bought its first radio in 1956, and the purchase reduced the father’s retirement savings by 10 percent!39

Despite the austerity of their living conditions — or perhaps because of it — they saved a large part of their incomes.

Depression, war, and reconstruction had all persuaded older people to set money aside, because they never knew what might happen next. They maintained the habit of saving long after the war. Younger people saved during this period for other reasons: to pay for future consumption, such as the educations and weddings of their children, and the new homes that many wanted to buy. In the absence of a generous system of social welfare, people also realized that they needed to save for their own retirements. Given these considerations, Japanese families saved at unusually high rates. At the beginning of this period, families put aside, on average, about 13 percent of their disposable incomes. As the economy grew and wages rose, they saved a little more each year. By 1974 the average family was saving 25 percent of its disposable income, a rate four to five times higher than the American savings rate.40

It was these savings, channeled through the banking system, that financed much of the expansion and renewal of Japan’s capital stock.

Japan’s economic expansion required more and better physical capital, but it also required more labour. Much of this labour was released from agriculture. In the first years after the war, as much as half of the labour force was engaged in agriculture. The destruction of the cities and the shortage of food had led many urban dwellers to return to their rural roots, and many discharged soldiers had nowhere else to go. Many of these people were minimally productive. There was some movement of workers back to the cities as Japan’s economy began to recover; but in 1955,

…nearly 16 million workers still toiled on Japanese farms; they constituted 41 percent of the nation’s labor force. In the same year, West Germany’s farm sector employed 18 percent of the labor force; the United States’, 9 percent; and England’s, 4 percent.41

By 1974, farm workers constituted only 14% of the labour force. Workers had been pulled out of the agricultural sector by the growing availability of well-paid employment in mining, construction, industry and commerce, and they had been pushed out by changes in agricultural technology.

Beginning in the late 1950s, labor-saving devices were introduced into farm areas with increasing rapidity. Mechanical threshers were among the first new devices; they saved hours of time once spent husking rice. Mechanical plows were next; they eliminated days of backbreaking labor preparing fields for transplanting. By the late 1960s, sprayers, grain dryers, mechanical planters and harvesters, and small trucks were becoming more widespread. All of these devices enabled farm families to maintain their plots with a much reduced investment of labor.42

A smaller number of farmers produced more food than ever before, allowing Japan to feed its increasingly urban population. Urban dwellers constituted 38% of the population in 1950, 76% in 1975.

The Dual Economy

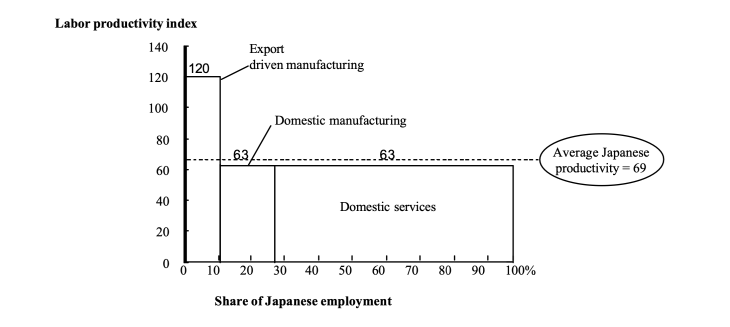

Japan’s industrial policy nurtured companies that would eventually compete on world markets and sometimes dominate them. Toyota, Sony, and Nintendo are three of the largest and most successful of these companies. They are highly productive, open to innovation, and attentive to the demands of consumers — as they must be if they are to survive in highly competitive markets. They are also quite unlike most firms in Japan. In the 1990s only 10% of Japanese workers were employed by firms that competed internationally. The remaining 90% worked at firms that sold goods and services domestically, and most of these firms did not compete on a national scale. They operated regionally or locally, and often benefited from laws and regulations that shielded them from competition. There was little pressure for them to be efficient or innovative. They did things as they had always been done.

This was the “dual economy”: a small number of very efficient firms that were internationally competitive, and a great number of inefficient firms that seemed immune to change. The dual economy was already apparent in the 1960s and became deeply entrenched in the 1970s and 1980s. The post-bubble stagnation of the 1990s left it intact.

The graph below illustrates the dual economy.43 The vertical axis shows Japanese productivity relative to American productivity; the horizontal axis shows employment. In the manufacturing sectors open to international competition — principally steel, automotive parts, metalworking, cars, and consumer electronics — Japanese workers were on average 20% more productive than their American counterparts. Japanese workers in domestic manufacturing and domestic services, by contrast, were only 63% as productive as American workers in the same sectors. Averaged over all employment, Japanese workers were only 69% as productive as American workers.

The dual economy of the 1960s is not surprising: the firms at the forefront of growth inevitably leave the others behind. What is surprising is the consolidation of the dual economy in the following decades. Yukio Hatoyama, Japan’s prime minister in 2009 and 2010, blamed industrial policy:

The vaunted industrial policy, which had nurtured many infant industries in the fifties and sixties, degenerated into the protection of sunset industries and never-do-well industries at the consumers’ expense.44

Two factors led to the deterioration of industrial policy. One was mission creep. The bureaucrats accelerated Japan’s early development by protecting infant industries and promoting the merger of subscale companies. The need for these policies diminished as the economy matured, but the bureaucrats, long suspicious of competition, continued to meddle in the workings of the economy. The second was the oil crisis of the early 1970s. The price of oil quadrupled, crippling heavy industry everywhere. The long-term impact of the crisis depended on the policy response. In the United States, for example, firms were forced to adjust to the new market conditions. The “rust belt” emerged as unprofitable factories were shut down and their workers laid off. Eventually, though, American firms pioneered energy-efficient and flexible methods of production, new factories were built, and the economy rebounded. In Japan, where the interests of employees mattered more than the interests of outside shareholders, firms that had become noncompetitive were shielded from market forces. And this protection, once enacted, was very hard to remove.

The protected manufacturing sectors included cement, glass, paper, petrochemicals, oil refining — even steel, which had been one of Japan’s leading industries before the oil shock. These industries were able to set high prices for their domestic customers because they were shielded from import competition. Japan’s byzantine regulations officially allowed and effectively discouraged imports. As well, users and producers made pacts under which the users agreed to buy only the domestic product, and the producers agreed not to sell anything at all to users who broke the pact. These policies were remarkably successful.

How could Japanese producers manage to charge domestic customers 60 percent more than world prices for steel, 70 percent more for cement, and 64 percent more for petrochemicals? Not surprisingly, in each of these industries,…imports as of 1992 remained negligible: only 1.2 percent of consumption in cement, 7 percent in steel, and 8 percent in petrochemicals.45

Japan’s domestic services, including retailing, healthcare, and residential construction, were “subscale, poorly managed, antiquated, insulated from competition, and woefully unproductive.”46 They survived through an array of government loans, rent subsidies, grants, tax provisions, and zoning restrictions. Japanese consumers bore the cash costs of these supports — their reward was high prices, inadequate choice, and poor service.

The dual economy would have been costly to Japan even if the two sectors had functioned separately, but of course, they did not. The efficient sector relied on the inefficient sector for much of its materials.

Every time Toyota builds or operates a factory in Japan, it pays more than its foreign competitors for the cement in the building, for all the steel, rubber, plastic and glass that go into its cars, even the electricity to run the plant.47

A full 30 percent of the input costs to manufacturing come from just four inefficient and shielded sectors where Japanese prices are far above world levels: energy, distribution, transport and communication.48

Japan had once been “the new kid on the block,” but those days were gone. It was now forced to compete with South Korea, China, Vietnam, and other rapidly industrializing countries. To lower their costs, export-oriented firms moved some of their production to jurisdictions where the input costs were lower and labour was cheaper. The relocation of production facilities “hollowed out” the efficient sector, further reducing the average productivity of Japan’s domestic production.

A shock to productivity caused Japan to shift toward the protection of inefficient industry, and that protection led to further declines in productivity. The decline in economic growth is evident in the figure above — and worse was to come.49

The Bubble and Its Aftermath

Japan was also experiencing structural problems at the macroeconomic level. Japan’s consumption had been low and its investment high in the immediate postwar period, and this pattern became more extreme as time passed. Between 1955 and 1973, real per capita consumption tripled because GDP was growing rapidly, but the share of consumption in GDP fell from 62% to 54%. Investment rose from 7% in 1955 to 25% in 1970. Both of these trends were problematic.

Investment had been invaluable when Japan had been a relatively poor country using outdated technologies, but the pay-off to investment was sharply lower once Japan had become prosperous and modern.

In the late 1960s, for every $1 that Japan added to its stock of capital, i.e., the value of all the infrastructure, factories, and equipment, Japan’s GDP grew by $1.22. But, by the 1980s, for every $1 in added capital stock, Japan’s GDP grew only $0.43.50

The collusive relationship between commercial banks and their affiliated firms allowed investment to continue, and indeed to grow, with only the most cursory evaluations of its profitability.

Output can only grow if there are willing buyers for the goods produced. Japan’s low domestic consumption meant that a significant part of its output had to be sold abroad, generating large trade surpluses. The flipside of these surpluses was trade deficits in the United States and in Western Europe. The governments of these countries recognized that their deficits were deflationary, suppressing both employment and growth. Trade disputes became increasingly common.

The position of the United States was particularly difficult. Its tight monetary policy led to high interest rates, which in turn led to strong capital inflows. These inflows caused the US dollar to appreciate by about 50% between 1980 and 1985, making foreign goods cheap for Americans to buy and American goods expensive for foreigners to buy. The United States had a trade deficit not just with Japan, but with other major industrial nations as well. The trade deficit, coupled with high domestic interest rates, was pushing the United States into recession.

The United States, Japan, West Germany, France, and the United Kingdom attempted to resolve this problem in 1985. They adopted the Plaza Accord, which committed them to market interventions that would depreciate the US dollar. The agreement signalled that the US dollar would soon reverse course, causing speculators to move away from assets denominated in the US dollar and toward assets denominated in other major currencies. The US dollar depreciated, as intended. The yen strongly appreciated — its value doubled between 1985 and 1988.

The appreciation of the yen was deflationary for Japan. The Bank of Japan attempted to offset this effect by reducing interest rates. Falling interest rates were the impetus for Japan’s asset price bubble.

As the prime interest was lowered from 5 percent to a postwar low of 2.5 percent, asset markets predictably skyrocketed. The value of commercially zoned property in central Tokyo, already the most expensive real estate in the world, jumped tenfold by 1989. By then, the Ministry of Construction calculated that, in theory, Japan could buy the entire United States, a nation twenty-five times its size, four times over. The Japanese stock market soared on the strength of the property boom. With the consent of the Ministry of Finance, Japanese banks allowed companies to take out loans against up to 80 percent of the value of their currently appraised land assets. Using their wildly inflated assets for leverage, firms engaged in so-called zaiteku (hi-tech finance) stock speculation, setting up special investment accounts to play the market. With operating profit margins squeezed by yen appreciation, even large companies like Toyota relied increasingly on “zaiteku profits” to “dress their books.” Supported by hot money and mass mania, the Nikkei index of leading Japanese stocks more than tripled between 1985 and 1989. By then the average price of stocks in the leading Nikkei 225 index traded at a multiple of more than seventy-eight times earnings, another historic high and nearly triple the average multiples of the early 1980s. By comparison, the January 1989 composite price/earnings ratio of the booming Dow Jones Industrial Average was 12.7.51

Financial speculation padded corporate profits. In 1987, non-operating revenues — largely zaiteku — generated 40% of company profits at Toyota, 65% at Nissan, 63% at Sony, and 134% at Sanyo.52 Speculation also changed the way decisions were made in the real economy.

People who bought stocks or real estate stopped caring whether the companies earned good profits or the buildings exacted high rents. Rather, in accordance with the “greater fool theory,” they bought these assets only because they expected someone else to pay an even higher price later on. To make matters worse, investors not only bought real estate for this reason; they also built it. The same thing happened with factories. As the stock market soared, it valued companies — and by implication, their factories — far in excess of what it actually cost to build those factories. Companies took this as a signal to build many more factories than the economy really needed.53

Many of these projects were unprofitable or only marginally profitable. The companies that undertook them would soon find that they could not repay their loans, and the banks that had issued the loans would be forced to recognize that the projects’ true value was far below their declared value.

The most dangerous words in business might be, “It’s different this time.” Every bubble has a backstory that explains why, just this one time, seemingly crazy behaviour is perfectly reasonable. In the case of Japan, it was claimed that Japan had developed a new form of capitalism that would allow its rapid growth to continue indefinitely. It was widely believed, both inside and outside of Japan, that Japan would soon replace the United States as the world’s most powerful economy. These beliefs were contradicted by facts that, as yet, no-one acknowledged. The efficient, world-beating sector of the economy accounted for only a tenth of employment, and the much larger inefficient sector was being propped up by a haphazard network of government initiatives. Industrial policy had once accelerated the growth of industries with great potential, but now served only “sunset industries and never-do-well industries.” Japan’s future growth depended on the willingness of other countries to accept huge trade deficits with Japan — willingness that very plainly was not there.

In May 1989, the Bank of Japan began to rein in an overheated economy. The interest rate reversed its course, rising from 2.5% to 6% by August 1990. High interest rates brought to a halt the rise in asset prices. But the prevailing prices could only be justified by the expectation of future capital gains; with that expectation gone, these prices were unsustainable. The Nikkei began to fall in February 1990 and had lost 45% of its value by October. The collapse of real estate prices was only a little smaller.

The financial and real economies were connected on the way up, and they were connected on the way down.

Japan’s postwar economic structure, built on an extraordinary level of leverage and a system of cross-shareholding between companies and banks, had been held together largely by the glue of appreciating assets. As both real-estate prices and stock prices fell, the glue melted…[GDP] growth slipped to 1.1 percent in real terms, the lowest level in more than sixty years.54

Weighed down by an average debt-to-equity ratio of more than 2.5 to 1, saddled with excess capacity, and earning next to nothing, firms cut back on capital expenditures by more than 8 percent on average in 1992-93. Moreover, manufacturers started cashing in on their renowned cross-holdings in other companies and liquidating long-term land assets just to cover operating expenses, which only increased the pressure on the ailing stock and property markets.55

Banks had issued loans against collateral that now had little value, and many of these loans were nonperforming. In 1990, 10% of all bank loans were nonperforming, and their total value amounted to 20% of Japan’s GDP.56 The banks, being so severely undercapitalized, had little ability to issue new loans.

The sharp decline in investment brought the economy into recession. The Bank of Japan again reversed course on interest rates; but the paralysis of the commercial banks, and the unwillingness of firms to incur still more debt, limited the effectiveness of monetary policy. An aggressively expansionary fiscal policy prevented Japan from falling into an even deeper recession, but seemed incapable of lifting it out of recession. Japan’s industrial output was smaller in 1998 than it had been in 1991.

Japan experienced a “lost decade” and then, in the early 2000s, began to recover. The recovery was tepid. Japan had become a middle-of-the-road developed nation with middle-of-the-road growth.

There is little doubt that Japan’s industrial policy was sometimes extremely beneficial. Automobile manufacturing and consumer electronics are two “infant industries” that became efficient, innovative, and flexible under the bureaucrats’ protection. But these examples do not imply that industrial policy was systematically beneficial. Japan’s industrial policy also protected industries that had lost their competitive advantage and would never regain it — steelmaking, aluminum refining, and petroleum refining being three such instances. It also protected firms that had no interest in either growth or change, condemning their sectors to perpetual inefficiency.

Industrial policy substitutes the judgment of the bureaucrat for the judgment of the market. The postwar history of Japan provides mixed evidence on the value of such a substitution.

- Based on the Madison Project database 2020. ↩

- Peter Duus and Daniel Okimoto, “Fascism and the History of Pre-War Japan,” The Journal of Asian Studies (1979), p. 68. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 13. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 16. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 15. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 23. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, pp. 24-5. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 18. ↩

- Janet Hunter, The Emergence of Modern Japan (Routledge, 1989), p. 169. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 37 and p. 38. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 109. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 18. ↩

- See James Fulcher, “The Bureaucratization of the State and the Rise of Japan,” The British Journal of Sociology (1988), pp. 239-42. ↩

- Fulcher, “The Bureaucratization of the State and the Rise of Japan,” p. 239. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 45. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 47. ↩

- Peter Duus, ed., The Cambridge History of Japan: The Twentieth Century (Cambridge, 1988), Table 10.4. ↩

- The historian Conrad Crane believes that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved Japanese lives by hastening Japan’s inevitable surrender. The surrender occurred in August, early enough that the Americans were able to bring in huge quantities of food before the onset of winter. These shipments kept millions of Japanese from starving. See Malcolm Gladwell, The Bomber Mafia (Little, Brown and Company, 2021), pp. 196-7. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 66. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 58. ↩

- A depression cartel attempts to ameliorate the effects of a cyclical recession on its existing members. A rationalization cartel attempts to co-ordinate a permanent reduction in output in an industry that has excess productive capacity. Both kinds of cartel can set prices and allocate output shares among its members. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, pp. 75-6. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History , p. 77. ↩

- Wartime coal production had relied on the forced labour of Chinese and Korean miners. SCAP repatriated these workers at war’s end, but there were too few Japanese miners to fill their places. See Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, pp. 179-80. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 181. ↩

- John Haley, “Governance by Negotiation: A Reappraisal of Bureaucratic Power in Japan,” Journal of Japanese Studies (1987), p. 355. ↩

- Yutaka Kosai, “The Postwar Japanese Economy, 1945-73,” in Peter Duus, ed., The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 6 (Cambridge, 2008), p. 92. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 10. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 10. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, pp. 102-3. ↩

- Japanese employment was not as secure as the term “lifetime employment” suggests. “Lifetime employment in Japan is not for life but until the middle or late fifties; and although wage raises are tied to seniority, job security is not: it is those with most seniority who are the first fired during business downturns because they are the most expensive. Lifetime employment also does not apply to the ‘temporaries,’ who may spend their entire working lives in that status, and temporaries constitute a much large proportion of a firm’s work force than any American union would tolerate (42% of the Toyota Motor Company’s work force during the 1960s, for example).” (Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 12.) ↩

- Yutaka Kosai, “The Postwar Japanese Economy, 1945-73,” p. 528. ↩

- Yutaka Kosai, “The Postwar Japanese Economy, 1945-73,” p. 528. ↩

- Japan joined GATT in 1955 and OECD in 1964. It was required to liberalize its trade and remove its capital controls, but it stretched out the period of adjustment as much as it could. The economy was not fully liberalized until the late 1970s. ↩

- Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, p. 264. ↩

- Based on Maddison Project Database 2020. Measured in “international dollars” at constant prices, Japan’s GDP per capita was 2,857 in 1948 and 18,226 in 1973. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 99. ↩

- About 40% of investment in the manufacturing sector was financed internally. (Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 100.) ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, pp. 79-80. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 101. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 84. ↩

- Allinson, Japan’s Postwar History, p. 107. ↩

- The graph is taken from McKinsey Global Institute, Why the Japanese Economy is not Growing (report, 2000). ↩

- Yukio Hatoyama, quoted in Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 22. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 42. ↩

- McKinsey Global Institute, Why the Japanese Economy is not Growing (executive summary, 2000) ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 48. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 48. ↩

- The figure is taken from Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 5. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 68. ↩

- David Asher, “What Became of the Japanese Miracle,” Orbis (1996), p. 216. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 221. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 216. ↩

- Asher, “What Became of the Japanese Miracle,” p. 218. ↩

- Asher, “What Became of the Japanese Miracle,” p. 218. ↩

- Katz, Japan: The System that Soured, p. 222. ↩