Based on Tirthankar Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010 (Oxford, 2020), and B. R. Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India (Cambridge, 2013)

India became an independent nation on 15 August 1947. Its economic policies would henceforth be geared to its own needs, and not to the needs of the British empire. But India’s economic policies were constrained by its resources, and these resources were not greatly changed by independence. The trains ran on the same rails, the peasants tilled the same plots of land, the monsoon winds blew with the same capriciousness. So, exactly what resources did India possess?

Agriculture

India was primarily an agricultural country, with rural occupations accounting for three-quarters of total employment. It was also a poor country — its per capita GDP was comparable to that of China — and to a large degree, its poverty followed from the state of its agriculture. Both water and land were scarce.

There were two major sources of water. The first was the great northern rivers that flowed out of the Himalayas. Canal-based irrigation systems fed the river water to adjacent lands, and wells dug through alluvial soil gave access to a high water table. The second was the monsoon rains, which fell predominantly in the northeast. The Ganges plains received more than 2500 mm (100 inches) of rain each year; the Indus plains received less than 500 mm. The Deccan plateau, which covers much of the interior of southern India, received between 500 and 1000 mm of rain — but most of the rain fell during the monsoon season, a period of only three months. Having no great rivers to supplement the monsoon rains, the plateau was arid for much of the year. Irrigation was more difficult here. The intense heat of summer evaporated water from reservoirs and canals, and wells had to be drilled into hard-rock aquifers, making them both costly and unreliable. Mechanized pumps were not available until 1945, so moving water against gravity required the labour of a team of bullocks.1

Access to water determined the nature of each region’s agriculture.

The ‘wet’, well-watered rice-growing areas of the agricultural heartlands of the great river deltas sustained the hubs of traditional civilisation. Structured and hierarchical, with extensive urban and cultural centres, these areas depended on capital- and labour-intensive rice cultivation, with rigid social distinction between the status of the landowners (high-caste, often Brahmin) and the labourers (low-caste, often untouchable). They were already supporting very high population densities by the eighteenth century, and could not easily expand further without exhausting the soil. By contrast, the ‘dry’ areas of upland India, notably in the Deccan, the Punjab and western Gangetic plain, were sparsely settled, semi-arid and grew millets and wheat irrigated by wells. Here agriculture was extensive [land-intensive], with long fallow periods, and was best organised by peasant families cropping their own lands.2

The scarcity of land followed from two factors. The first was that there was simply too little arable land to sustain India’s people. The second was that ownership of the land was poorly distributed.

More than one-fifth of all rural households (22 percent) owned no land at all. Another 25 percent owned fragments of land or less than one acre. An additional 14 percent owned uneconomic or marginal holdings of 1 acre to 2.5 acres. In brief, the majority of all rural households, approximately 61 percent, either owned no land, or small fragments of land, or uneconomic and marginal holdings…All of them together owned less than 8 percent of the total area. These were the recruits in the army of the chronically unemployed and underemployed, the millions of the rural poor precariously subsisting just at the border or slipping below the line of poverty. They could be contrasted with what passed for large landowners in India, the upper 13 percent of all households who had more than 10 acres and owned about 64 percent of the entire area, and the even smaller elite of the upper 5 percent having 20 acres or more, and owning 41 percent of the area…Holdings in all size groups were subdivided into separate parcels that were scattered within and between villages…”Large” holdings of 10 acres or more were commonly separated into seven or eight parcels of 2, 3, and 4 acres. “Large” landowners, therefore, tended to operate small holdings. They did not enjoy advantages associated with economies of scale.3

This ownership pattern ensured that tenancy and sharecropping4 were widespread.

Landowners with tiny plots leased out their holdings to other cultivators, and sought additional employment outside the village. “Large” landowners leased out part of their holdings because they tended to have several scattered plots that they found impossible to manage without the aid of tenants. The incidence of tenancy was highest in the densely populated rice deltas where land-man ratios were least favorable. It was not unusual for 30 to 40 percent of all cultivators to take some land on oral lease, or for the proportion of the area operated under such sharecropping arrangements to reach levels of 40 percent or more.5

The scarcity of both water and land made for inefficient agriculture. Indian foodgrain yields were “among the lowest in the world” and stagnant. In the four decades before independence, India’s population grew by more than 40%, but its production of foodgrains grew by only 12%.6

The scarcities of water and land were linked: more cropland could be created by extending the irrigation system. Between 1900 and 1939, India’s cropland expanded by 30 million acres, of which 24 million acres were newly irrigated land.7

The basic unit of rural society was the village and its surrounding fields.8 The villages tended to have entrenched hierarchies, with the population divided by religion, caste, land ownership and economic status, and (especially after independence) political connectedness. At one time, they were largely self-sufficient: villagers engaged in handicrafts such as handloom weaving, or the production of leather goods, furniture, metal tools and utensils, carpets, or pottery, to satisfy the village’s own needs. But from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, India’s increasing openness to trade made the villages less autonomous. Farmers shifted toward cash crops such as cotton, sugar, and jute, and the expanding network of roads and rails that carried away these crops also brought in mass-produced goods. Some handicrafts (notably cotton spinning) became uncompetitive and disappeared, while others adapted and survived.

The hierarchical structure of the villages, along with the political connectedness of their elites, would become important factors after independence. The Indian government would find that devising policies for the betterment of the poorest farmers was one thing, getting them implemented was another.

Industry

Modern industry established itself in India in the first-half of the twentieth century. Modern industry grew as quickly in India as it did in Japan, a country known for the ferocity of its industrialization, but India’s modern sector had been so small before 1900 that even five decades of growth didn’t make it very big. Most of India’s industry at independence was not modern: it was based in households and small workshops, employed traditional technologies, and used little machinery.

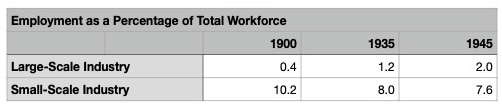

Historians distinguish between large-scale (modern) industry and small-scale industry. Large-scale industry was characterized by “use of machinery and steam-powered technology; large factories and large-scale employment of wage labour; and legal identity, such as being subject to the factory act or the company act.”9 Small-scale industry was characterized by the absence of these attributes. The tables below show how each category of Indian industry evolved during the early twentieth century.10 Employment in large-scale industry rose slowly between 1900 and 1945, offsetting a mild decline in small-scale industry, but even in 1945, small-scale industry employed nearly four times as many people. Employment as a percentage of the workforce shows the same trends. Note that even in 1945, industry as a whole employed less than ten percent of the workforce.

Industry’s share of total output grew faster than its share of employment, reaching 16.3% in 1945. The growth in industry’s share largely reflects the shift towards large-scale industry, where workers were more productive than they were elsewhere in the economy.

Small- and large-scale industry sought to exploit India’s natural resources in different ways.

Small-scale industry concentrated in the interior — mainly Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Madras — whereas large-scale industry concentrated in the port cities. This pattern appeared because large-scale industry depended on overseas trade, ports, and banks. The small-scale industry depended more on local markets, materials, and skills available locally. Textile production dominated both. Next in importance were food processing, metals, wood products, and hides and skins. In short, industries intensive either in natural resources (cotton, metals, minerals, animal substances) or labour dominated the composition of both.11

Cotton textiles illustrate this pattern. The traditional method of making cloth was to spin the cotton fibers into yarn by hand, and then weave the yarn into cloth using a handloom. Machine spinning produced yarn so cheaply that it displaced hand spinning in the nineteenth century, but machine weaving did not likewise displace handloom weaving. Instead, the handloom weavers specialized in both low-end and high-end textiles. They produced cheap and coarse cloth for peasant needs, and finer cloth that incorporated traditional designs for the urban market. As late as the 1930s, handloom weaving employed more people than all of large-scale industry.12 Modern textile production began in 1854, when the first steam-powered cotton mill was built in Bombay. There were 58 mills by 1880 and 271 mills by 1914. The yarn spun in these mills was sold to handloom weavers in India and China. Later, the loss of the Chinese market (to Japan) induced the mills to begin making their own cloth. Mill cloth and handloom cloth served different segments of the textile market, allowing them to coexist.

Rural poverty forced peasants to supplement their incomes in any way they could. Both small- and large-scale industry depended upon the cheapness of their labour. Many traditional handicrafts survived in the villages only because some income was better none, and modern industry relied on the peasants’ willingness to work for low wages.

The peasant family sent men to factories and kept women at home to do household work and mind the land. While the factory wage was low, combining agricultural work back home and factory work in the city could increase total earnings for a family with land. City work was not an alternative to rural work. The purpose of migration was not escaping distress, but to increase family incomes, reduce risks, and retain a hold in the rural economy.13

The availability of cheap labour made investment in machinery less profitable. Indian workers used less machinery and older technologies than did their foreign counterparts, and were consequently less productive.

The labour–machine ratio was higher in the cotton mills of Bombay than anywhere else in the world. Bombay had no problem competing with England or America because wage levels were low. But when Japan emerged as a competitor, Bombay faced problems, because Japan had low wages and more efficient factories…In 1921–5, the average production per person of a coal mine in India was 40 per cent of that in the United States of America…In 1914–22, on average each employee of Tata Steel produced less than five tonnes of finished steel per year. The corresponding average for United States of America was 53 tonnes.14

The producers of capital-intensive goods — including machinery, metals, and chemicals — did not greatly benefit from India’s cheap labour, so they could not easily compete with foreign firms. They were slow to develop, skewing India’s industrial structure toward labour-intensive production. “The textile industries still supplied about 30 per cent of both output and factory employment in 1947; the rest of the industrial sector comprised a small amount of production across a large range of products.”15

Factory wages started to rise by the 1920s, and a middle class composed largely of “service workers such as traders, bankers, doctors, skilled artisans, factory workers, and engineers working in the factories” emerged.16 Another important change was the movement of India’s entrepreneurs, long active in trade and finance, into the industrial sector. During the colonial era, large enterprises were very often owned and financed by British entities and operated by British expatriates. Their roles dwindled over time, and by the 1920s, Indian entrepreneurs were outpacing them. The Tata family is an example of this phenomenon. It had been associated with trade and cotton mills since the 1870s; but in 1907, the family founded the Tata Iron and Steel Company. The company was satisfying more than two-thirds of India’s steel requirements by the late 1930s.17

Indian entrepreneurs were most numerous in the great port cities of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. They used their new wealth to develop urban institutions.

At the time of Indian independence, these cities were homes to some of the best schools, colleges, hospitals, universities, banks, insurance companies and learned societies available outside the Western world. A big part of that infrastructure had been created by the Indian capitalists.18

Trade

The volume of global trade expanded massively in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, slowed only by the Great Depression of the 1930s. This expansion was driven by two factors. One was the Industrial Revolution that began in Britain. Steam-powered and mechanized factories produced huge quantities of low-cost goods, forcing industrialists to find new markets for manufactured goods and new sources of raw materials. The second was the sharp fall in transportation costs caused by two new technologies, the railway and the steamship. Falling transportation costs integrated national markets and facilitated overseas trade.

The per capita incomes of the industrializing countries grew rapidly, and the gap between their per capita incomes and those of the rest of the world grew steadily larger. A popular interpretation of the divergence in per capita incomes is that the industrializing countries became rich at the expense of the rest, that they “transferred surplus” to themselves. The empirical evidence does not support this interpretation. Europe’s industrialization led to faster growth of per capita incomes everywhere. Incomes did not diverge because the “third world” became poorer; they diverged because the “third world” grew less quickly than the industrial core. The figure below summarizes this evidence (India accounts for almost all of “South Asia”).19

The West’s industrialization increased the third world’s rate of growth because markets linked the two areas together. The West needed more raw materials and partially processed goods; the third world produced them. The West produced high-quality manufactured goods at ever lower prices; the third world replaced domestically produced goods with imported goods. No authority had to engineer these changes: they occurred in response to evolving market opportunities.

The Industrial Revolution and the transportation revolution — these were the forces that governed India’s trade in the century before independence. The volume of foreign trade (exports plus imports) doubled between 1880 and 1914.20

Railways facilitated the integration of the Indian economy by dramatically reducing transportation costs. Railway freight rates in 1930 were “94 percent less than the charges for pack-bullocks in 1800–40, and 88 percent less than those for bullock carts in 1840–60.”21 Low freight rates allowed peasants to switch from subsistence farming to cash crops. Their produce was sent to industrial centers for processing or to the ports for export. The organization and financing of this trade were largely carried out by indigenous traders.

The British were a nation of merchants and tireless advocates of free trade. The colonial government in India developed the ports and built the connecting network of railroads. Duties on both imports and exports were (with a few notorious exceptions) low or zero. The British navy guarded the sea routes, and British agents assisted Indian traders abroad. The result was a great expansion of India’s foreign trade. One tonne of goods passed through three major ports in 1840; thirty-nine million tonnes of goods passed through eight major ports in 1939.22

There was not unanimous agreement that the expansion of trade was beneficial. Mahatma Gandhi imagined a future for India in which most people lived in self-sufficient villages. Large-scale industry and foreign trade were to be discouraged because they impeded local self-sufficiency. And in the years before independence, Indian nationalists claimed that the British had “de-industrialized” India to create a market for British goods — hand spinning and small-scale ironmaking were two handicrafts that had all but disappeared.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that India gained from both its exports and its imports. The opportunity to export allowed India’s peasants to shift away from subsistence farming, which was already near its limits, and towards crops for which world demand was growing. In the early twentieth century, more than half of India’s exports consisted of agricultural goods such as cotton and jute, or lightly processed agricultural goods such as yarn. The ability to import facilitated the adoption of modern technologies. The railways are one such example: the construction engineers, the rails, and the rolling stock were all brought in from abroad in the early years. Later, India would train its own engineers, forge its own rails, and build its own rolling stock — but the trains had been running for decades before it did so. Likewise, Indian entrepreneurs were able to build India’s first cotton mills because the machinery could be purchased “off the shelf” in Britain, and because British technicians could be brought in to get the mills running and keep them running. Modern technology, both as equipment and as knowledge, was a commodity that could cross borders.

Of course, trade brought with it new forms of uncertainty, a factor that Nehru emphasized. The world economy was constantly evolving, constantly churning out winners and losers. India primarily exported agricultural goods and imported manufactured goods. It gained when the prices of the former goods rose relative to the prices of the latter goods, and it lost when the opposite occurred. India consistently gained from 1875 until 1925: worldwide demand for agricultural goods rose, pushing up their prices, and technological progress brought down the prices of manufactured goods. India consistently lost after 1925, because worldwide overproduction of agricultural goods depressed their prices. Likewise, India lost when Britain mechanized its cotton industry ahead of India, and gained when India mechanized its cotton industry ahead of China. India initially gained from the expansion of global trade because most bulk commodities were transported in sacks, and the preferred sacking material was jute, almost all of which was grown in Bengal. It relinquished these gains when new methods of transporting bulk commodities developed and the market for sacking material collapsed. Trade made more things possible and fewer things certain.

In the early twentieth century, the low productivity of Indian industry and the volatility of the international economy led India’s businessmen to demand tariff protection. By 1940, tariff protection was widespread.

Infrastructure

The colonial government was a small one. Tax revenue in 1931 was only 3% of GDP, in part because the government had limited ability to impose higher or broader taxes. Taxes on agricultural land were a significant source of revenue (as they had been for centuries), but with agriculture itself struggling, the tax rate could not be very high. Another significant source of revenue was the income tax. It primarily fell on groups whose incomes were easily monitored, such as landlords and civil servants; the self-employed escaped it entirely. Customs and excises were more easily imposed, and some customs duties were set very high to protect domestic producers; but commodity taxes are regressive — they fall more heavily on the poor than the rich — so concern for the poor limited their use.23

Comparisons with other countries show just how small the Indian government’s revenues were.

In the 1920s, nominal tax collection per capita was less than 2 per cent of tax per head in Britain (adjusted by purchasing power, 6 per cent). British India was poor also in relation to most of Britain’s tropical colonies and other Asian countries in the interwar period. Between 1920 and 1930, the government of the Federated Malay States spent on average more than ten times the money spent in British India per head, that of Ceylon spent more than three times, those of the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies more than double.24

The government augmented its spending power by borrowing in the London market. It did not, however, borrow large amounts, and Britain’s payments to India for services rendered during World War II were large enough to wipe out the accumulated debt. At independence, India held a positive sterling balance in London.

The government allocated funds to routine matters such as administration and debt service, but the largest single budget item was always military spending. The military sustained British rule, safeguarded British investments, and supported British interests in other countries. Once funds had been allocated to these things and a few other obligatory items, there wasn’t much money left — certainly, there was too little money to fund a sustained and comprehensive development program. Despite this constraint, the colonial government was able to make substantial improvements to India’s infrastructure.

At Independence in 1947, the visible legacy of colonial rule in South Asia was the modern infrastructure that the regime had left behind—the ports, canals, the telegraph, sanitation and medical care, urban waterworks, universities, postal system, courts of law, railways, meteorological office, statistical systems, and scientific research laboratories…

The absence of an explicit developmental goal imposed unevenness in the way these assets were created. There were huge regional inequalities in the supply of these goods…Nor was there one way of funding these assets. Private investors built the railways; the state guaranteed a return to capital. Canals and roads were a state investment. Administration differed too. Initially, the military departments built and managed some of these assets. Over time, administrative departments took over the task. A division of labour evolved. The provinces looked after roads, schools, and healthcare; the federal government looked after the railways.25

The purpose of irrigation was to ease extreme seasonal water shortages, which reduced agricultural productivity and raised the risk of famine. Irrigation was limited by two constraints. The first constraint was that irrigation could not conjure water out of nothing: it could only make better use of the water resources that naturally existed. This constraint meant that some regions had far more potential than others (the Deccan, for example, would always be unpromising territory). It also meant that there could be no “cookie cutter” irrigation projects: each project had to be individually designed to make best use of an area’s particular water resources. The second constraint was the government’s limited spending power. Irrigation projects were undertaken when there was room in the budget for them. During the interwar period, when the government’s financial resources tightened, the government could do little more than maintain the existing irrigation system. Nevertheless, the colonial government did substantially add to the irrigation system: 22% of the cropped land was irrigated by 1938.26

The development of the Indian railway system was another major accomplishment. The first passenger train in Britain (and the world) went into service in 1830, and the first passenger train in Germany went into service in 1835, using a locomotive designed and built in Britain. India’s first passenger train went into service in 1853, indicating a relatively quick (for the times) adoption of a modern technology. Australia’s first passenger train started two years later.

The railway system expanded rapidly. There was less than a thousand miles of track in 1860, almost 24,000 miles in 1900 and almost 42,000 miles in 1940. The railways carried 604 million passengers and 129 million tonnes of freight in 1940.27

The railways were initially financed and built by private entrepreneurs, with the government guaranteeing them a 5% return on their investment. The guarantee must have seemed a clever idea to a cash-strapped government, but it led to inefficient use of the railways. Freight rates were set too high and too few goods were carried, so the rail lines frequently failed to earn their 5% return, forcing the government to bear costs that it had hoped to avoid. The government slowly became more involved in the railway system; by 1924, it both owned and operated the railways.

The government also oversaw the development of telegraph and postal systems, ports and power stations. It did comparatively little on social matters like education and health, instead relying on the provinces, or on private spending, to take care of them.

Boundaries

There was one way in which independence did drastically change India’s resources. The newly independent state lost territory that had been part of British India, and gained territory that had not been part of British India.

Partition — the division of British India into two independent countries, India and Pakistan — had been debated for more than a decade before it actually occurred. Muslims, worried about their cultural and religious prospects in a country dominated by Hindus, imagined a northern homeland for themselves. Pakistan was to be this homeland. At first, no specific political structure was assigned to it: it could be a group of provinces within India, or it could be a sovereign country.

As late as the provincial elections of 1937, Pakistan was not a pivotal issue for most Muslims. The All India Muslim League advocated its creation, but the election results show that the League “barely had any presence in the Muslim-majority provinces,” including Sind, Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), and Bengal. The League’s support was strongest in provinces in which Muslims were a minority and hence more fearful of Hindu domination. The dominant party in the 1937 elections was the Indian National Congress, the foremost proponent of Indian independence.28

The provincial elections of 1946 revealed much sharper divisions, with the League winning 87% of the seats reserved for Muslims and Congress winning 90% of the general seats. Congress continued to lead the campaign for Indian independence. It argued that all of British India should become a single independent state — the Muslims’ concerns could be addressed later. With independence imminent and Congress intransigent, Muslims looked to the League to protect their interests.

The League’s position on a Muslim homeland had been spelled out by the Lahore Resolution of 1940, which

… framed the Muslims as a “nation” and not a “minority.” It urged for a Muslim homeland to be constituted in the Muslim-majority provinces in north-west and north-east India. The sovereignty and the constitution of these states and their relation to India were to be decided in the future.29

It was not until March 1946 that the League took the position that the Muslim homeland could not be accommodated within an Indian state, that it had to be an independent nation.

If India’s borders could be challenged, so could those of the provinces. Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs argued for the partition of their province: the Muslim-majority part would join Pakistan, the Muslim-minority part would remain in India. Bengal’s Hindus likewise supported the partition of their province.

The Mountbatten Plan set out the rules for India’s transition to independence. The Hindu-majority provinces would remain part of India. The provincial assemblies of the Muslim-majority provinces (Bengal, Punjab, Sind, NWFP, and Baluchistan) would decide whether to remain in India or become part of a sovereign Pakistan. The plan was accepted by representatives of the Muslims, the Hindus, and the Sikhs in June 1946.

The provincial assemblies of Punjab and Bengal voted to partition their provinces in June 1947.30 The other assemblies voted to bring their provinces into Pakistan.

Boundaries were hurriedly drawn between a Muslim-majority West Punjab and a Hindu-majority East Punjab, and between a Muslim-majority East Bengal and a Hindu-majority West Bengal. It was an impossible task. Wherever the line was drawn, there would be substantial religious minorities on both sides of the line. Wherever the line was drawn, peasants would be separated from their fields, workers from their employers, worshippers from their shrines, families from their kinfolk.

Sectarian violence began a year before independence day. It started in Bengal, spread across the north, and exploded in Punjab. Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs living in areas where they were a religious minority, were killed or driven away. Ultimately, between one and two million people would be killed.31

Bengal and Punjab were the most violent provinces, but there were substantial differences between them.

Bengal had a long history of often bloody conflict between Hindus and Muslims, dating back to (at least) the last decades of the nineteenth century. By contrast, in the Punjab the different communities had lived more or less in peace – there were no significant clashes on religious grounds before 1947. In Bengal large sections of the Hindu middle class actively sought Partition. They were quite happy to shuffle off the Muslim-dominated areas and make their home in or around the provincial capital. For several decades now, Hindu professionals had been making their way to the west, along with landlords who sold their holdings and invested the proceeds in property or businesses in Calcutta. By contrast, the large Hindu community in the Punjab was dominated by merchants and moneylenders, bound by close ties to the agrarian classes. They were unwilling to relocate, and hoped until the end that somehow Partition would be avoided.

The last difference, and the most telling, was the presence in the Punjab of the Sikhs. This third leg of the stool was absent in Bengal, where it was a straight fight between Hindus and Muslims. Like the Muslims, the Sikhs had one book, one formless God, and were a close-knit community of believers. Sociologically, however, the Sikhs were closer to the Hindus. With them they had a roti-beti rishta – a relationship of inter-dining and inter-marriage – and with them they had a shared history of persecution at the hands of the Mughals.

Forced to choose, the Sikhs would come down on the side of the Hindus. But they were in no mood to choose at all. For there were substantial communities of Sikh farmers in both parts of the province. At the turn of the century, Sikhs from eastern Punjab had been asked by the British to settle areas in the west, newly served by irrigation. In a matter of a few decades they had built prosperous settlements in these ‘canal colonies’. Why now should they leave them? Their holy city, Amritsar, lay in the east, but Nankana Saheb (the birthplace of the founder of their religion) lay in the west. Why should they not enjoy free access to both places?32

The violence in Punjab was extreme and burned itself out in a few years. The violence in Bengal was chronic, lingering for decades.

In the course of four years between 1947 and 1951, recent scholarship estimates that around 14.5 million people moved between India, West Pakistan [now Pakistan], and East Pakistan [now Bangladesh], and an additional 3.7 million were ‘missing’ or dead. In these years, the pace of migration was swifter and greater on the border between India and West Pakistan, and was a two-way process that petered out by the end of 1949. In contrast, migration in eastern India had begun in the wake of the riots of 1946, and, although things remained relatively calm during the days leading up to the Partition and after, migration, especially of Hindus from East Bengal to West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura, continued steadily…The migration across the eastern border lasted nearly two decades after the Partition and was characterized by its chronic intensity. In this time frame, at least 6 million Hindus crossed into India and 1.5 million Muslims left India for East Pakistan.33

The massive migrations between India and Pakistan meant that each country came into existence with a worsening refugee crisis that would take years to resolve.

Pakistan was the territory lost; the princely states were the territory gained.

The princely states had never been incorporated into British India. They were ruled autocratically and, very often, not well.

Even in their heyday the princes got a bad press. They were generally viewed as feckless and dissolute, over-fond of racehorses and other men’s wives and holidays in Europe. Both the Congress and the Raj [British colonial government] thought that they cared too little for mundane matters of administration. This was mostly true, but there were exceptions. The maharajas of Mysore and Baroda both endowed fine universities, worked against caste prejudice and promoted modern enterprises. Other maharajas kept going the great traditions of Indian classical music.34

The princely states were not entirely autonomous. They had ceded all external matters to the British colonial government, and although they retained formal control of their own internal affairs, they were monitored and advised by British agents.

There were more than 550 of these states. The largest state by area was Jammu and Kashmir, followed closely by Hyderabad — each of them was about the size of Britain itself. The largest states by population were Hyderabad (16 million), Mysore (7 million), Jammu and Kashmir (4 million) and Gwalior (4 million). On the other hand, the smallest states encompassed only a handful of villages.

India’s absorption of the princely states occurred in two steps. First, the states signed the Instrument of Accession, which ceded defence, external affairs, and communications to the Indian government. Almost all of the states had done so by 15 August 1947. Second, the Indian government negotiated with each prince a settlement under which the prince gave up his administrative powers in exchange for a pension. This step, along with the administrative reorganization of India, was not completed until 1950.

The absorption of the princely states added an area of roughly half a million square miles to India (about 40% of its total area), and increased its population by 90 million. Of course, this land and these peoples had always been part of the “Indian” economy; what changed was that, for the first time, the whole of the Indian Peninsula came under the direct control of a single authority.

Go to: Indian Socialism, 1947-1966

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 65. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 29. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy 1947-2004 (Oxford, 2005), p. 97. ↩

- In sharecropping, a peasant works a landowner’s field in exchange for a share of the crop. It is an alternative to the owner hiring labour at fixed wages, or the peasant renting land at a fixed cost. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 97. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 96. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 59. ↩

- There were 558,000 villages in India in 1951. The population at that time was 361 million. (Census of India, 1951, Part IA — Report, p. 41.) ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 140. ↩

- The data are from Table 5.1 of Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010. Roy cites S. Sivasubramonian, National Income of India in the Twentieth Century as his source. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, pp. 143-4. ↩

- From Roy’s Tables 5.1 and 5.3: large-scale industry employed 1.8 million people in 1935; hand loom weaving employed 2.1 million people in 1932. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 172. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, pp. 174-5. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, pp. 82-3. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 81. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 109. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 225. ↩

- The graph is based on data from Tables 1.2 and 1.3 of Jeffrey Williamson, Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind (MIT Press, 2013). Williamson’s work is discussed here. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 78. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 44. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 77. ↩

- Customs are taxes imposed on imported goods; excises are taxes imposed on particular commodities regardless of their origin. ↩

- Tirthankar Roy, “The British Empire and the Economic Development of India (1858-1947), Journal of Iberian and Latin American History (2015), p. 219. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, pp. 212-3. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, p. 215. ↩

- Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-2010, Table 8.1. ↩

- Haimanti Roy, The Partition of India (Oxford, 2018), ch. 1. ↩

- Haimanti Roy, The Partition of India, ch. 1. ↩

- In both provinces, members of the assembly representing Muslim-majority areas voted against partition, while members representing Muslim-minority areas voted for it. Under the Mountbatten Plan, a vote in favour of partition by either group triggered partition. ↩

- Ramachandra Guha, India after Gandhi (Picador India, 2007), p. 32. ↩

- Ramachandra Guha, India after Gandhi , pp. 12-3. ↩

- Haimanti Roy, The Partition of India, ch. 3. ↩

- Guha, India after Gandhi, pp. 37-9. ↩