Based on Stephen Broadberry, “Accounting for the Great Divergence,” manuscript (March 2021); Robert Brenner and Christopher Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” Journal of Asian Studies (2002)

At any time before the end of the Middle Ages, the vast majority of the world’s people lived in dire poverty. Then, in the seventeenth century, the standard of living began to rise in western Europe. A gap between European and Asian standards of living emerged, growing steadily larger until the late twentieth century.

In both Europe and Asia, the pace of economic development varied greatly from country to country, and even from locality to locality within a country. The differences within Europe and Asia swamped the differences between them, making it difficult to identify the gap’s origins. The historian Kenneth Pomeranz dealt with this problem by narrowing the comparison. He compared the most economically advanced part of Europe, Britain, to the most economically advanced part of China, the Yangzi delta. The Great Divergence is the name that he gave to the emergent gap between their standards of living.

Pomeranz identified Britain as Europe’s economic leader because he believed that the gap appeared during the Industrial Revolution. More recent research has shown that the gap appeared at a much earlier date, necessitating a broader definition of the Great Divergence. As it is used here, the term refers to the gap between the living standards of the most economically advanced parts of Europe and China. The most advanced part of Europe was first Italy, then the Netherlands, and then Britain. The most advanced part of China was always the Yangzi delta. Europe’s tag team appears to have decisively outperformed the Yangzi delta beginning in about 1700. The explanation for this divergence lies in substantive and fateful differences in the two regions’ economies.1

The Great Divergence in Numbers

GNP per capita is the best single measure of labour productivity and of a population’s material well-being. The figure below shows a reconstruction of this statistic for the Yangzi delta (black line) and the European leader (grey line).2 The European leader is Italy until 1540, the Netherlands from 1550 to 1790, and Britain after 1800. Each area’s GNP per capita is converted into a fictional common currency, the 1990 international dollar, using purchasing power parity exchange rates.

Reconstructions like this one are based on fragmentary data and incomplete knowledge of the prevailing institutions, with a Chinese series having a less complete evidentiary base than a European series. Some economic historians do not trust them, but they are our best window into the past.3

The figure shows that the Great Divergence had two causes, faster economic growth in Europe and economic collapse in the Yangzi delta. Both graphs are relatively trendless until perhaps 1650, when the European graph begins a climb that accelerates after 1820. The graph for the Yangzi delta turns sharply downward in about 1700, and the delta’s GNP per capita is cut in half over the course of the next century.4 The productivity gap — the Great Divergence — emerges in 1700 and grows steadily.

Agriculture

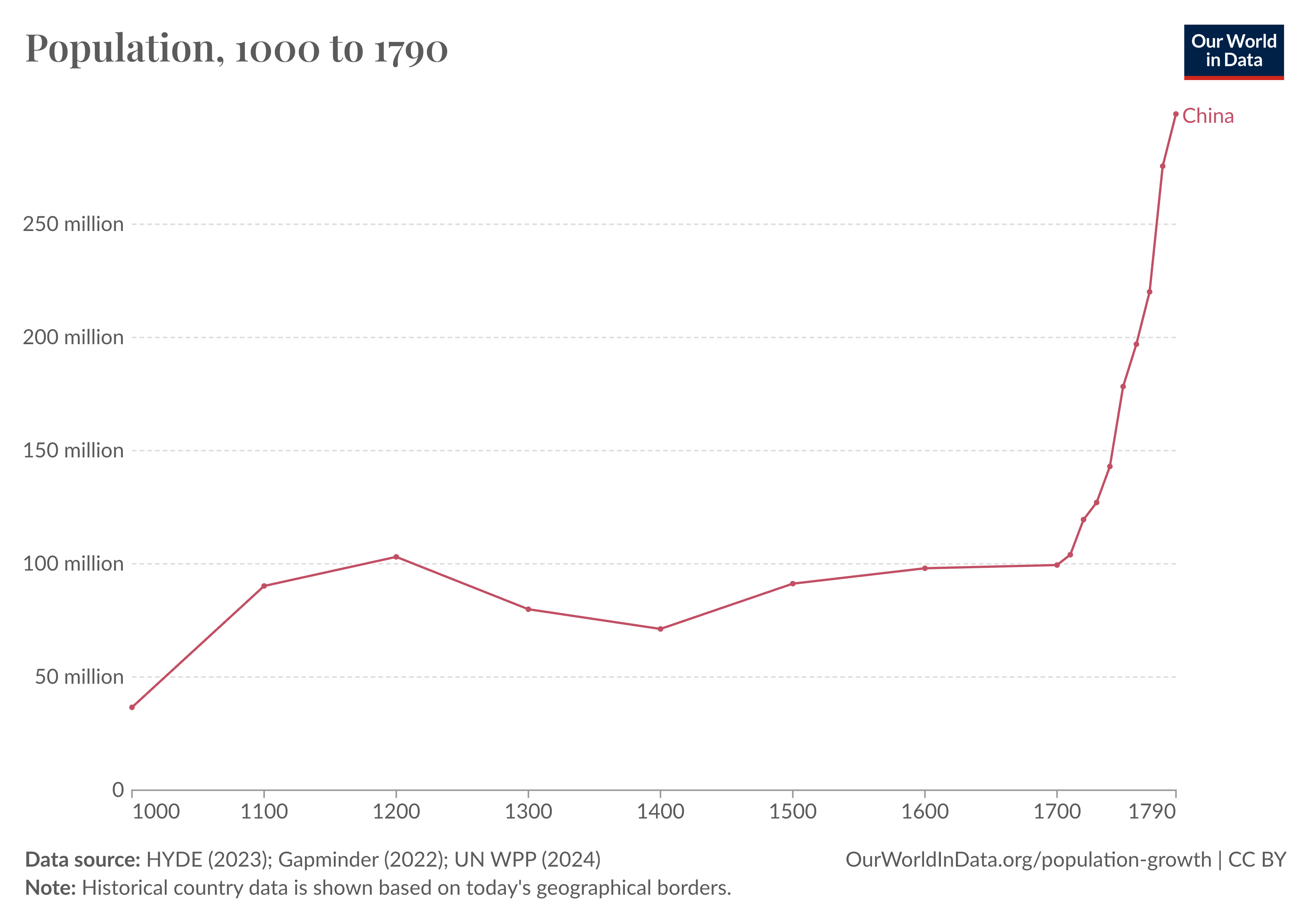

Agriculture dominated the economies of the pre-modern world, so it is not surprising that the Great Divergence had its origins in this sector. China experienced a Malthusian crisis in the eighteenth century. The number of peasants grew more rapidly than the quantity of arable land, so farm families had to make do with progressively less land. Labour productivity fell, as did output per capita. Two factors allowed England to avoid a similar crisis. First, it experienced an agricultural revolution that allowed it to support a much larger population. Second, its population growth came much later, when it was already industrializing. The additional labourers were absorbed by the industrial and commercial sectors, and any shortfall in agricultural produce was relieved through trade with the European (and later, American) hinterland.

The demographic histories of China and England are shown in the figures below. Brenner and Isett emphasize that these histories should not be treated as exogenous. Each country’s demographics were driven, at least in part, by the nature of its property rights.

Landlords owned much of China’s agricultural land. Their dealings with their tenants were mediated by the state in ways that were advantageous to both parties. The principal advantage to the landlords was the security of their rents. By the eighteenth century,

…landlords had consolidated their legal ownership of the land and thereby their ability to take what was an essentially politically set level of rent, which, in the Yangzi delta, amounted to 40 to 50 percent of the summer harvest — rice in the paddy zone and cotton in the cotton belt. Since the burden of taxes had been shifted onto property owners, and rentier landlords paid their taxes out of their rent receipts, the Qing state upheld and enforced the right of landlords to garner rents from their tenant.5

China’s elite captured 30-40% of the annual harvest under this system. The principal advantage to the tenants was the security of their tenancy: the fixity of rents meant that they did not have to outbid other peasants for the use of the land.

The seeming advantages of administratively fixed rents led to serious problems over the longer term. Landlords had no incentive to invest in land improvements because they would not share in the incremental harvest. More importantly, peasants, shielded from competition, were free to pursue ends that ultimately led to less efficient land use.

In order to secure social insurance against illness and old age, as well as to ensure the continuity of the patriline [male line of descent] necessary for ancestral worship, peasants typically tried to assure that sons who would care for them and perform the appropriate rites survived to adulthood.6

Infant mortality was high and life expectancy was short, so people married young and had many children, hoping for at least one son who would outlive his parents. The parents of sons who reached adulthood

… subdivided their holdings, in land, tools, and liquid wealth, in order to provide those sons with the wherewithal for their own maintenance, early marriage, and family formation. The outcome was large numbers of children per woman, rapid population growth and, consequently, a trend to ever smaller peasant plots and the de-concentration of peasant wealth more generally.7

Each generation of farmers had less land than the one that came before it. In the Yangzi delta, the average plot size fell from 1.875 acres to 1 acre between 1620 and 1850. 8

The peasants of medieval England behaved much like their Chinese counterparts: they married early, had many children, and subdivided their land holdings. As in China, the average plot size declined as the population grew. But the Black Death brought this regime to an end in the middle of the fourteenth century, and a new regime arose in its place. Landlords established more complete property rights over land, and then consolidated the arable land into large fields that they rented to independent farmers. The rents were determined by market forces, making them affordable only to the most efficient farmers. Small farms could not be efficient, so the subdivision of holdings stopped, and small farms were absorbed by large farms.

By 1800 English farms were on average ten times larger than in the late middle ages and twice as large as in 1600. They were also 130 times larger than contemporaneous farms in the Yangzi delta.9

The sons (except for the eldest, who inherited the farm) had to make their own way and accumulate their own resources. This requirement forced them to marry later, and later marriage led to smaller families.

These differences in Chinese and English property institutions led to stark differences in the evolution of population:

Between 1600 and 1750, average female age of marriage [in England] was about twenty-six, significantly higher than in most of the medieval epoch and far higher than the average of eighteen or so in the Yangzi delta. The female celibacy rate was correspondingly elevated, at 25 percent across the seventeenth century and 11 percent during the first half of the eighteenth century, whereas that in China was near zero. The resulting total fertility rates in England were thus a mere 4.25 and 4.61, respectively, in these successive periods compared to 6.5 or so in the Yangzi delta: about 32 percent lower.10

Agricultural Productivity in the Yangzi Delta

Agriculture in the Yangzi delta was not stagnant: new crops were introduced and new techniques were adopted. But these innovations could not offset the impact of declining plot size. Agricultural labour productivity fell steadily, and the only way to compensate for the declining effectiveness of labour was to work more.

During the late Ming and Qing, peasants did succeed in raising yields from their ever more diminutive plots — by weeding more thoroughly, by spreading more fertilizer, and by adding a winter wheat crop that matured before rice planting. But in each case they were required to add labor inputs that failed to yield returns in grain as high as those yielded by already existing labor inputs. Thus higher output per unit of land was secured through the sacrifice of output per unit of labor.11

The volume of work also rose because an earlier tendency to substitute animal labour for human labour was reversed. Animals had to be fed, so reverting to human labour meant that more of the harvest was available for human consumption. Farmers in the Yangzi delta had almost entirely given up animal labour by the end of the Ming dynasty (1644). Output per unit of land was maintained, but once again, output per unit of labour fell.12

The peasants were also harmed by environmental decay that was apparent by 1644.

Environmental depletion and degradation flowed from the intensification of multiple cropping, from eroding the thinner soils of hills, from terracing the landscape, from exploiting large areas of China’s forests for fuel and timber and above all, from reclaiming woodland for arable farming. Reclamation involved the felling of trees…which eroded surrounding soils and destroyed natural buffers against flows of [waterborne] soil, silt and stones.13

Unchecked rainwater carried away the fertile soil, clogged the irrigation canals with silt, and damaged the transport waterways upon which China’s regionally specialized economy depended. The construction and maintenance of these waterways had been a great accomplishment of the Chinese state, but the state failed to protect them from the acceleration of environmental damage. The fiscal institutions of the Ming and Qing states simply did not generate enough revenue to maintain infrastructure that was under ever greater stress, and neither regime attempted to reform these institutions in a significant way.14

Despite the improvements in crops and technique, the peasants’ lives became increasingly straitened. Brenner and Isett estimate that in the Yangzi delta, grain output per capita fell by 30% between 1600 and 1800.15 The peasants worked longer and harder, but were nevertheless driven closer to subsistence levels of consumption.

Agricultural Productivity in England

In England, by contrast, the productivity of agricultural labour rose steadily, so that by 1800, “each English farm worker produced enough to support two workers in manufacturing and services.”16 The increase in productivity facilitated a shift away from agricultural labour. In 1500, agricultural workers constituted 74% of the English population; in 1800, they were only 35% of the population.17

Early productivity gains came from the shift away from the medieval “open fields” system, under which the fields were divided into numerous narrow strips over which individual peasant families held hereditary tenancy claims. The peasants had to coordinate their work to some degree, and economies of scale could not be exploited. There was common access to grazing and waste land, so there was little incentive to improve this land. The “open fields” system was gradually eliminated through the landlords’ accumulation of land and its consolidation into large enclosed fields, and by the emergence of a class of market-oriented tenant farmers.

Larger farms made possible the elimination of the massive disguised unemployment that had weighed down medieval agriculture. Medieval peasant farms were on average about fourteen acres, with 80 percent of the land under farms of twenty acres or less and 46 percent under farms of ten acres or less. Nevertheless, since a family labor force producing bread grains was quite capable of operating with its own labor farms of up to fifty acres with only minimal seasonal assistance, it is evident that the farms of the early modern period — which averaged fifty-nine acres in 1600 and covered better than 60 percent of the land with units over one hundred acres — brought about an enormous increase in the efficiency of the allocation of agricultural labor.18

More efficient use of labour was not the only benefit of the new system. Enclosure extinguished common access to the land, so that all of the benefits of land improvements accrued to the improver. Land improvements became profitable and were often undertaken after an enclosure.

In 1300, there were perhaps 2 million acres of improved meadow and pasture and 20 million acres of common grazing. By 1700, about 7 million acres of common had been improved, and, in the eighteenth century, a further 8 million acres of waste [land] were converted to pasture.19

Improvements in crops and methods also increased the productivity of English agriculture. Cows gave more milk, sheep produced more fleece, the harvest from an acre of planted wheat grew larger.

The practice of “fallowing” fields — letting them lie idle to restore their fertility — was gradually abandoned in favour of four-crop rotation. Each field was planted with a sequence of crops — wheat, turnips, barley, and clover — that repeated every four years. The farm’s arable land was divided into four parts, each at a different stage of the sequence, so that each crop was available every year. The wheat and the barley were for human consumption. The turnips were fodder that could carry livestock through the winter. The clover was for grazing; it also restored the soil’s fertility through nitrogen fixation. The manure of the grazing animals provided further fertilization.

Four-crop rotation directly increased agricultural productivity because all of the arable land was always planted with something valuable. As well, the planting of fodder crops supported livestock, so England’s substitution was the opposite of China’s: horses and other draught animals increasingly replaced humans as sources of power.

Agricultural labour productivity trended downwards in the Yangzi delta but moved steadily upwards in England. There, “between 1500 and 1750, agricultural labor productivity grew by between 52 and 67 percent.”20

The consolidation of land was the main driver of productivity growth but it wasn’t the only one. England’s commercial and industrial expansion gave workers the opportunity

…to enlarge their consumption beyond the bread, beer and meat that marked affluence in the late middle ages. Well-off workers could consume the newly abundant products of the tropics – pepper and other spices from the Indies, coffee, tea and sugar. In addition, “luxury” manufactures were also added to the normal standard of consumption. These luxuries included books, clocks, cutlery, crockery, better furniture and so forth.21

Agricultural workers who wanted these things could move to cities where the wages were high, or they could stay and contend with competition’s inexorable demand:

A competitive world offers two possibilities. You can lose. Or, if you want to win, you can change.22

Many of them chose change, as was recognized even in the nineteenth century. Gibbon Wakefield (1796-1862) wrote,

In England, the greatest improvements have taken place continually, ever since colonization has continually produced new desires among the English, and new markets wherein to purchase the objects of desire. With the growth of sugar and tobacco in America, came the more skilful growth of corn in England. Because in England, sugar was drank and tobacco smoked, corn was raised with less labour, by fewer hands.23

Industry

Economic growth before the Industrial Revolution was largely “Smithian growth.”

The driving force behind economic improvements in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations is productivity gains attending division of labor and specialization. By producing what they are best suited to produce and exchanging their products with others, people capture the benefits of comparative advantage at the market place. Division of labor is limited only by the extent of the market. As the market expands, the opportunities for Smithian growth increase accordingly. 24

Market expansion, and its attendant growth, could be driven either by greater population density or by greater prosperity.

Pomeranz’s claim that the Great Divergence occurred in the nineteenth century was premised on the belief that the Yangzi delta and England had been developing in much the same way before that time. Specifically, he believed that both regions had been experiencing Smithian growth. But what looked like Smithian growth in China was actually something different, the product of deprivation rather than prosperity. This understanding of Chinese development supports a much earlier date for the Great Divergence.

The Yangzi Delta

The secular decline in the size of a peasant family’s holdings meant that the family had to work longer to maintain its consumption. It did more weeding, applied more fertilizer, planted an additional crop each year. But each new activity added less to the harvest than the activities that were already being undertaken.

Imagine the peasants having a list of tasks that they could undertake to maintain their consumption as plot sizes fell. The list is organized, running from the most valuable task at the top of the list to the least valuable at the bottom. The peasants work their way down the list, taking on progressively less rewarding tasks as their lives become increasingly straitened. Most of the items on the list deal with farming, with the direct production of food, but one item on the list — call it proto-industry — is different. It requires the peasants to produce goods at home, to be sold for the cash needed to buy food, fertilizer and other essentials. It is near the bottom of the list: the peasants take it up only when they are running out of options.

The dominant proto-industry was the production of cotton textiles. The peasants grew the cotton, spun the raw cotton into thread, and wove the thread into cloth.

Cotton appeared first in Jiangnan, an area to the south of the Yangzi River. The soil there was ill-suited to paddy cultivation, so the peasants planted dry-land crops such as wheat, barley, and legumes. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, population growth resulted in the division of the land into smaller and smaller plots, forcing the peasants to work the land more intensively to maintain their consumption. But dry-land crops benefit little from extra effort, so the peasants soon reached the bottom of their lists. “On a portion of their land, peasants thus began to grow cotton, a crop that would respond to higher labor inputs, and simultaneously turned to domestic spinning and weaving to work up the raw material for sale on the market.”25

The parts of the Yangzi delta where paddy cultivation was dominant also shifted toward growing cotton and producing cotton textiles, but at a slower pace. Rice benefits from labour intensification, so the peasants were slower to reach the bottom of their lists. But there is little doubt that when they did move towards cotton, they did so out of necessity: the value of a day’s labour in rice cultivation was as much as two and a half times greater than the value of a day’s labour in textile production.26

Home production was primarily carried out by the female and elderly members of the family (the younger males took care of the farm work). They were tied to the farms — their labour was cheap for that reason — so there was little incentive to replace home production with workshop production.

More generally, the move toward proto-industry did not result in a significant degree of urbanization.

Because peasants could muster such minimal demand for non-essentials potentially produced in the towns, the size of the urban population was primarily dependent upon elite demand and thus upon the size of the surpluses that elites (landlords, merchants, and officials) could extract — mainly landlords’ rents, but also merchants’ profits and lenders’ interest, and state salaries…In the 1840s, only 11 percent of the delta’s population at most lived in towns of over eight thousand people…The best estimate for the proportion of people in nonagricultural pursuits, in the delta’s town and country taken together, is 15 percent.27

There was industry in the Yangzi delta, but it was not transformational, as it was in England even before the Industrial Revolution.

England

The Yangzi delta moved into proto-industry through the exhaustion of existing options. England moved into it through the opening up of new options.

From the fifteenth through the early seventeenth centuries, the most dynamic section of English industry, the production of undyed and undressed cloth, had grown up as heavily export-oriented in response to the demand for luxury textiles of the trans-European elite (mostly lords). But over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as output per person in agriculture made for cheaper food and allowed the English population to devote an ever greater part of its income to discretionary expenditures, there emerged a wide range of consumer goods industries to meet a rising “mass” domestic market for manufactures.28

The expansion of demand made possible the division of labour and returns to scale that characterize true Smithian growth. The profitability of this kind of manufacturing created more discretionary income and more opportunities for Smithian growth — a virtuous circle of the kind that underlies the Keynesian multiplier.

Consumers found that they had to devote a declining proportion of their income to food and thus could allocate an increasing proportion to discretionary expenditures. The resulting increase in demand for manufactures raised their rate of return ever higher with respect to agricultural output, and districts that initially combined industry with pastoral or dairy production increasingly sloughed off agriculture and came to specialize entirely in manufacturing production. One therefore witnesses, especially from the second half of the seventeenth century, not only ever larger and more complex industrial districts,…but the emergence and efflorescence of full-fledged, major manufacturing cities that would, in due course, house the industrial revolution — Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds.29

Between 1500 and 1800, the urban population rose from 7% of the total population to 29%, making England the second most urbanized country in Europe (after the Netherlands).30

By 1800…England had, in a very real sense, ceased to be an agricultural country.31

Cultural Divergence and The Industrial Revolution

Pomeranz argued that England and the Yangzi delta developed in much the same way until the mid-nineteenth century, when the Yangzi delta’s explosive population growth pushed it into a Malthusian crisis. England escaped the same fate only by crazy good fortune. The discovery of the New World gave England “ghost acres” that helped to feed its growing population. Its coal deposits were also crucial: England avoided environmental disaster by switching from an economy organized around organic matter (like horses and trees) to one organized around inorganic matter (like coal and iron). The Industrial Revolution followed as a matter of course. Had circumstances been somewhat different, Pomeranz suggested, China might have industrialized before England.

For the reasons set out above, the claim of parallel development until the mid-nineteenth century is not credible. The hypothesis that New World acreage and coal deposits were critical factors in England’s industrialization has also been powerfully contested.32

Furthermore, the suggestion that the Industrial Revolution was a natural consequence of sustained development is out of step with the extensive literature on the Industrial Revolution’s origins. Joel Mokyr’s work (here) is especially important in this context. He argued that Europe underwent an intellectual transformation in the centuries before the Industrial Revolution. This transformation included the reassessment of science that culminated in the Scientific Revolution, as well as the philosophical movement known as the Enlightenment. The impact of these events was felt throughout society. They led to the mathematization of studies that previously had been only qualitative, the adoption of new research methods, and the accumulation of useful knowledge of all kinds. The Industrial Revolution has been characterized as a “wave of gadgets.” These gadgets were the product of new ways of thought, and in this sense, they were more than a hundred years in the making.

No comparable intellectual transformation occurred in China. Confucianism, with its emphasis on order and fidelity, was China’s unchallenged philosophy for more than two thousand years. China’s scientific tradition emphasized practical knowledge over abstractions, and was largely incompatible with modern science.

Arguably, the Industrial Revolution was the manifestation of a different kind of divergence — a philosophical or cultural divergence. Such a divergence was recognized by the statesman Ding Richang (1823-1882). Confronted with the superiority of European weapons over Chinese weapons during the Opium Wars, he observed,

The Westerners…have been expending their intelligence, energy, and wealth on things that were completely vague and intangible for hundreds of years; the effects are now suddenly apparent.33

- The term “Great Divergence” was taken from Kenneth Pomeranz’s book, The Great Divergence (Princeton, 2000). Pomeranz’s thesis was that Britain and the Yangzi delta developed in similar ways until the early 1800s, when both regions were on the verge of a Malthusian crisis. Britain was saved from its crisis by “fortuitous” events (often encapsulated as “coal and colonies”) that facilitated the Industrial Revolution. China was not as fortunate and was not saved. This thesis was immediately controversial and inspired decades of research and debate. Today, very little of Pomeranz’s thesis remains intact. My intention in this post is not to describe the ins and outs of the debate, but to summarize its current state. ↩

- This figure is Figure 6 from Broadberry, “Accounting for the Great Divergence.” ↩

- For a discussion of the problems associated with Chinese historical reconstructions, see Kent Deng and Patrick O’Brien, “The Tyranny of Numbers,” in John Hatcher and Judy Stephenson, eds., Seven Centuries of Unreal Wages (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). For a discussion of the methods and data used in this particular reconstruction, see Stephen Broadberry, Hanhui Guan and David Li, “China, Europe, and the Great Divergence,” Journal of Economic History (2018), beginning on p. 659. ↩

- Although the graph is visually arresting, the rate of decline was actually very slow, averaging a little more than one-half of one percent per year over the eighteenth century. The cumulative effect of this slow but persistent decline was devastating. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 615. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 616. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 616. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 616. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 619. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 619. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 621. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 621. ↩

- Patrick O’Brien, The Economies of Imperial China and Western Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 41. ↩

- O’Brien, The Economies of Imperial China and Western Europe, p. 50. O’Brien argues (p. 54) that the state’s inadequate response to environmental and demographic pressures “can be held responsible for possibly the largest and most significant share of the Qing empire’s inadequate…economic performance between 1683 and 1911.” ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 624. ↩

- Robert Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective (Cambridge, 2009), p. 60. ↩

- Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Table 1.1. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 626. ↩

- Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, pp. 62-3. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 627. ↩

- Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, pp. 76-7. ↩

- Lester Thurow. ↩

- Quoted by Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, p. 77. Here, the word “corn” means food grains such as wheat and barley. ↩

- Bin Wong, China Transformed (Cornell University Press, 1997), p. 16. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 631. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 631. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” pp. 632-3. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 635. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” pp. 635-6. ↩

- Allen, The Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Table 1.1. ↩

- Brenner and Isett, “England’s Divergence from China’s Yangzi Delta,” p. 636. ↩

- See, for example, Jan de Vries, “The Great Divergence after Ten Years: Justly Celebrated yet Hard to Believe,” Historically Speaking (2011), and Patrick O’Brien, “Ten Years of Debate on the Origins of the Great Divergence,” Reviews in History (2010). ↩

- Quoted by Tonio Andrade, The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History (Princeton, 2016), p. 280. ↩