Francine Frankel, India’s Political Economy 1947-2004 (Oxford, 2005), and Arvind Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought (Oxford, 2024)

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, was a committed socialist. He implemented three five-year plans — the last ending in 1966 — that emphasized the growth of heavy industry, predominantly in the public sector, and self-sufficiency through import substitution. Nehru’s socialism outlived him, as India was slow to move away from his policies after his death.

How Successful were Nehru’s Economic Policies?

Arvind Panagariya has written,

Most analysts, including those critical of India’s controlled regime, broadly approve of the economic policies and performance during the 1950s. Differences between the advocates of pro-market and state-driven development strategy relate principally to the period beginning in the early 1960s.1

The grounds for this assessment is a modest increase in India’s growth rate.

India grew 2.0 percent per annum on a per capita basis during 1951–65…This performance was superior to India’s own prior performance during any historical period for which systematic data are available.2

There are two difficulties with this comparison. The first is that the British colonial government was so poorly funded that it was unable to implement a comprehensive development policy. Nehru’s development policy is being compared to no development policy — surely an easy benchmark to beat. The second is that the Indian economy (like every other economy) has been buffeted by one-time external events, including the Great Depression of the 1930s and the fall in agricultural prices during the late nineteenth century. Attributing the difference in growth rates between any two time periods to India’s own policies, without attempting to adjust for this kind of external shock, is somewhere between risky and wrong.

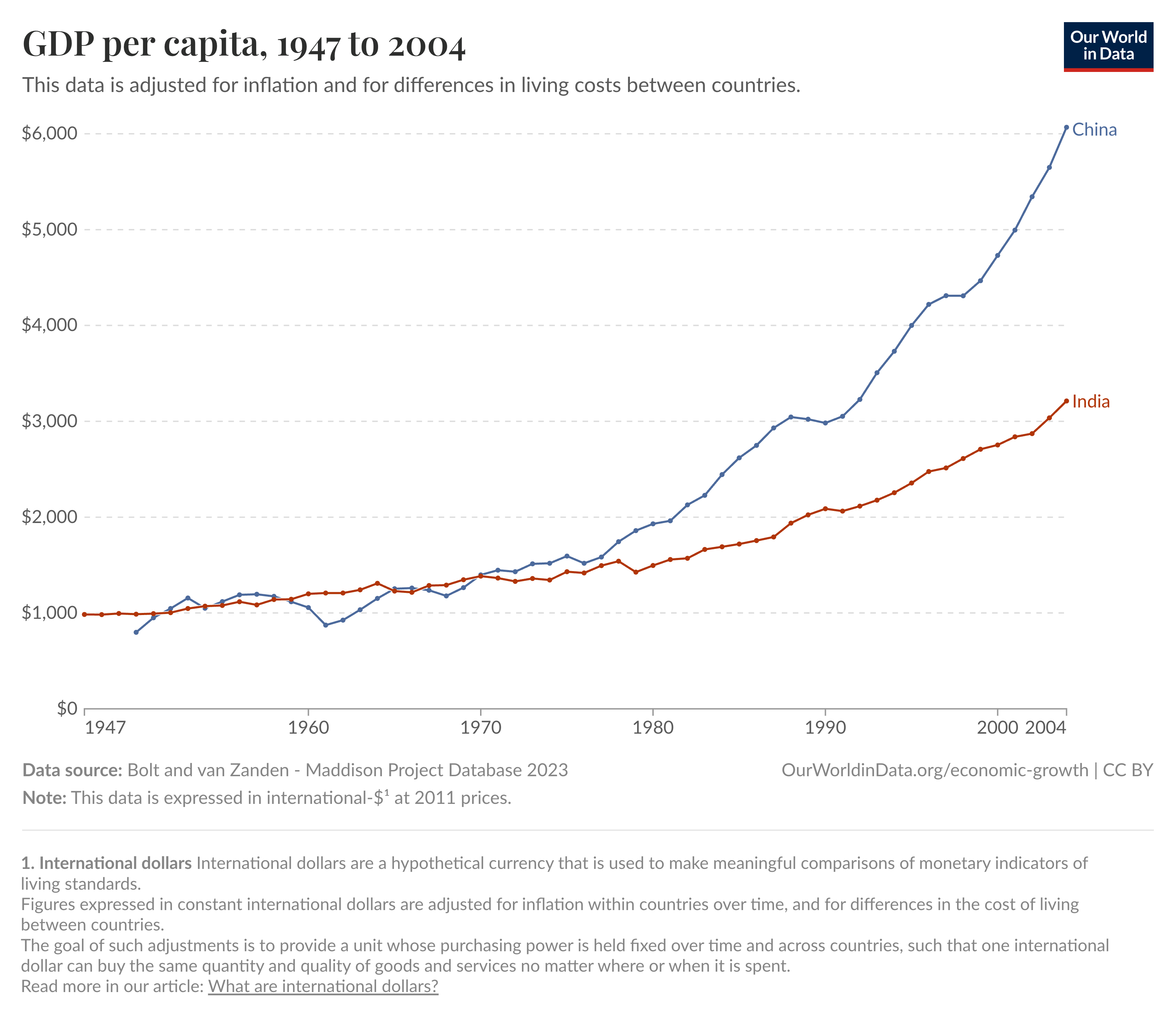

Another way of assessing Nehru’s economic policies would be to compare India to China. India achieved independence in 1947; the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. Both countries were large, densely populated, primarily agricultural, and committed to socialism. How did their subsequent economic development match up?

The figure above shows GDP per capita for the two countries. There was very little difference between the two countries until 1978, when Deng Xiaoping radically reformed the Chinese economy. After this date, the Chinese economy massively outperformed the Indian economy.

The Indian economy under Nehru kept pace with the Chinese economy under Mao. Mao’s economic policies are widely understood to have trapped China in an impoverished state from which Deng’s policies finally released it. If Mao’s policies were inadequate, how can Nehru’s no-more-successful policies be commendable?

The Ideologues: Gandhi and Nehru

Mahatma Gandhi searched for truth — for existential knowledge — through nonviolent resistance to behaviour that obscured it. This search required him to oppose every form of social injustice:

No man could be actively nonviolent and not rise against social injustice, no matter where it occurred.3

Despite the worldly nature of his activism, Gandhi considered it to be inseparable from

… a living belief in God, meaning a self-existent, all-knowing Living Force which inheres [in] every other force known to the world, and which depends on none and which will live when all other forces may conceivably perish.4

He who denies the existence of that great Force, denies to himself the use of that inexhaustible Power…He is like a rudderless ship which, tossed about here and there, perishes without making any headway.5

Gandhi’s economic vision was premised on the belief that there is resource sufficiency rather than (as Western economists assert) resource scarcity.

It is the fundamental law of Nature, without exception, that Nature produces enough for our wants from day to day; and if only everybody took enough for himself and nothing more, there would be no pauperism in this world, there would be no man dying of starvation in this world.6

Social pathologies such as starvation are caused by an unequal distribution of Nature’s bounty, and it is man alone that is responsible for this distribution. A practitioner of nonviolent resistance tries to improve the distribution through social activism and personal austerity. Gandhi explained his own austerity in this way.

If somebody else possesses more than I do, let him. But so far as my own life has to be regulated…I dare not possess anything which I do not want. In India we have got many millions of people who have to be satisfied with one meal a day, and that meal consisting of a chapati containing no fat in it and a pinch of salt. You and I have no right to anything…until these many millions are clothed and fed. You and I, who ought to know better, must adjust our wants, and even undergo voluntary starvation in order that they may be nursed, fed, and clothed.7

One person’s austerity has little direct impact on the distribution, but one person’s example can convert others to the path of nonviolent resistance, and these converts can secure still more converts. It is not beyond belief, said Gandhi, that one person’s example eventually converts an entire community, bringing forth a just society.

Gandhi contrasted his “socialism” with conventional socialism. The Gandhian socialist acts on his beliefs without reservation, even if he must act alone, while conventional socialists “go on giving addresses, forming parties and hawk-like seize the game when it comes [their] way.” The Gandhian socialist renounces all forms of coercion and violence. Truth and violence are everywhere in opposition, so truthful ends cannot be attained through violent means. Conventional socialists, on the other hand, cannot imagine achieving their ends except through “untruthful” violence and coercion. The more they strive for a just society, the farther they recede from it.

Gandhi believed that

True civilization is that mode of conduct which points out the path of duty. Performance of duty and observance of morality are convertible terms.8

He believed that India’s traditional village supported and sustained this mode of conduct. The village was self-sufficient in food and simple manufactures, so villagers had what they needed and little more. The villagers engaged in manual labour, which Gandhi deemed to be morally necessary, and they were bound together by the village’s network of mutual rights and obligations.

The contemporary village was a diminished version of the traditional village. Cash crops were replacing subsistence crops, bringing the villagers into the money economy. With money came calculations of profit, and a concern not for today’s needs but tomorrow’s desires. Mechanisation had the same unwholesome effect, and by allowing one person to do the work of many, it robbed some villagers of the opportunity to do meaningful manual labour. And both of these innovations eroded the village’s cohesion.

Gandhi believed that the villages had to be restored. The khadi movement, which encouraged a return to hand-spun and hand-woven cloth, was part of this restoration. Gandhi also advocated the reform of the village hierarchy. The hierarchy itself was not problematic — Gandhi believed that it was both natural and effective — but the linking of roles to status was unwarranted. For him, “the prince and the peasant, the wealthy and the poor, the employer and employee” were ”on the same level.”9 He accepted the Hindu caste system as role differentiation, but believed the diminished status of some castes — especially the untouchables — was a distortion of true Hinduism. He acknowledged the position of the major landowners — the zamindars and the taluqdars — atop the village hierarchy, but did not believe that they were entitled to either significant extra wealth or higher status.

Zamindars and taluqdars tended to be relatively wealthy and locally powerful. Gandhi did not doubt that they took more of the village resources than they required, leaving the peasants impoverished and sometimes starving. But he adamantly opposed the expropriation of their land under any sort of “land to the tiller” policy, because expropriation was violent and therefore untruthful. His preferred policy was conversion of the landowners. A converted landowner would recognize that he does not have a right to the land’s produce, that he merely holds the land in trusteeship for the good of the community. He would strive to make the land as productive as possible, and then equitably distribute its produce.10

Gandhi imagined that in the future, the Indian economy would be dominated by the villages. There would be little large-scale industry, and without industry, there would be no need for people to congregate in cities. The Indian people would live a “simple but ennobled life,” while other parts of the world struggled with the burdens of industrialization.

Britain had done well as the first country to industrialize, but now faced competition from the United States, Germany, and Japan. Gandhi believed that the market for industrial goods was limited, and that this competition would lead to the competitors’ downfall. The Great Depression supported this view, leading Gandhi to write,

Don’t you see the tragedy of the situation, [namely] that we can find work for our 300 million unemployed, but England can find none for its three million and is faced with a problem that baffles the greatest intellects of England? The future of industrialism is dark.11

India’s way was the better way.

This land of ours was once, we are told, the abode of the Gods. It is not possible to conceive [of] Gods inhabiting a land which is made hideous by the smoke and the din of mill chimneys and factories.12

This utopian vision of India’s future might suggest that Gandhi was detached from the harsh realities of India’s present day, but he was not. He mediated disputes between peasants and landlords and between workers and industrialists, and he was fearful of what would happen if these disputes devolved into the kind of class conflict promoted by conventional socialism. Frankel explains,

Gandhi’s glorification of the Hindu peasant as the repository of an ancient spiritual wisdom was inspired mainly by imaginings of what the villager had been and could become again in the absence of both indigenous and imported corruptions. The peasant as he was profoundly distressed, and even frightened Gandhi. He comprehended that once aroused, impoverished millions — ignorant, degraded, and simmering with centuries of pent-up hostilities and hatreds — could easily overwhelm their tormentors and take a terrible revenge. With this haunting vision in view, Gandhi pleaded with the landlord class to “read the signs of the times [and] revise their notion of God-given right to all they possess.” He warned bluntly: “There is no other choice than between voluntary surrender on the part of the capitalist of superfluities…[and] the impending chaos into which, if the capitalist does not wake up be time, awakened but ignorant and famishing millions will plunge the country.”

Gandhi was no more sanguine about the capacities of desperate factory workers to resist the appeals of radical rhetoric…He pointed out: “In the struggle between capital and labor, it may generally be said that more often than not, the capitalists are in the wrong box. But when labor comes fully to realize its strength, I know it can become more tyrannical than capital…The question before us is this: When the labourers, remaining as they are, develop a certain consciousness, what should be their course? It would be suicidal if the labourers [were to] rely only on their numbers or brute force.”13

Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu extremist only a few months after India achieved independence. A Gandhian faction in government attempted to perpetuate his vision of a pastoral India, but they only influenced policy when Gandhi’s vision could be aligned with Nehru’s competing vision. Two instances of this alignment were support for village industry, and the attempt to compress village hierarchies by establishing rural co-operatives and empowering the panchayats (village councils). Gandhi’s philosophy also lay behind the idea that the Indian National Congress should be a “big tent,” as open to the industrialist and the zamindar as it was to the peasant and the labourer.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the only son of a prosperous lawyer, was raised in a privileged and cosmopolitan environment. He was educated in England, at Harrow, Trinity College, and — having decided upon a legal career — London’s Inner Temple. He was tangentially exposed to socialism, but seems to have been little affected by it. He had only an abstract understanding of the poverty endured by the vast majority of his countrymen.

Nehru was drawn into politics through the nationalist movement. He first met Gandhi in 1916. Gandhi was 47 and not yet the leader of the Indian National Congress; Nehru was 27. Nehru would remain loyal to Gandhi until the latter’s death.

Nehru had no first-hand knowledge of village life until 1920, when he became involved — at first reluctantly, and then wholeheartedly — with striking peasants in Oudh.

Looking a them and their misery and overflowing gratitude, I was filled with shame and sorrow, shame at my own easy-going and comfortable life and our petty politics of the city which ignored this vast multitude of semi-naked sons and daughters of India, sorrow at the degradation and overwhelming poverty of India.

I listened to their innumerable tales of sorrow, their crushing and ever-growing burden of rent, illegal exactions, ejections from land and mud hut, beatings; surrounded on all sides by vultures who preyed on them — zamindar’s agents, moneylenders, police; toiling all day to find that what they produced was not theirs and their reward was kicks and curses and a hungry stomach. Many of those who were present were landless people who had been ejected by the landlords, and had no land or hut to fall back upon. The land was rich but the burden on it was very heavy, the holdings were small and there were too many people after them. Taking advantage of this land hunger the landlords, unable under the law to enhance their rents beyond a certain percentage, charged huge illegal premiums. The tenant, knowing of no other alternative, borrowed money from the money-lender and paid the premium, and then, unable to pay his debt or even the rent, was ejected and lost all he had. This process was an old one and the progressive pauperisation of the peasantry had been going on for a long time.14

Nehru, like Gandhi, recognized the urgent necessity of village reform, but his remedies and priorities were not the same as Gandhi’s. He had begun to reconsider socialism. At first he had only “vague ideas, more humanitarian and utopian than scientific,”15 but he soon absorbed elements of Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Nehru accepted Marx’s contention that his philosophy was “scientific,” and was attracted to historical materialism’s claim that revolutionary change was inevitable. He wrote in 1936,

History came to have a new meaning for me. The Marxist interpretation threw a flood of light on it, and it became an unfolding drama with some order and purpose, howsoever unconscious, behind it. In spite of the appalling waste and misery of the past and the present, the future was bright with hope.16

Nehru also absorbed Lenin’s idea that the mass production of late-stage capitalism could only be sustained if the capitalist countries found new sources of raw materials and new markets for their output. These needs drew the capitalist countries into imperialism and exploitive colonization.17 Trade was the channel through which exploitation occurred, leading Nehru to conclude that India could only avoid exploitation if it became economically self-sufficient. Heavy industry was a blemish for Gandhi, a necessity for Nehru.

Heavy industry was just one facet of Gandhi’s and Nehru’s opposing positions on mechanization. Gandhi’s belief that manual labour was a moral necessity led him to write,

Mechanization is good when the hands are too few for the work intended to be accomplished. It is an evil when there are more hands than required for the work, as is the case in India.18

Nehru, on the other hand, was pragmatic.

If the masses lack anything, is it bad to produce it in sufficient quantities for them? Is it preferable for them to continue in want rather than have mass production? The fault obviously is not in the production but in the folly and inadequacy of the distributive system.19

But a better distributive system would require a radical restructuring of the economy.

Capitalism necessarily leads to exploitation of one man by another, one group by another, and one country by another…The only alternative that is offered to us is some form of socialism, that is, the state ownership of the means of production and distribution. We cannot escape the choice and…we cannot but cast our weight on the side of socialism.20

The socialist concepts of class and class struggle, spurned by Gandhi, were embraced by Nehru.

Congress cannot escape having to answer the question now or later, for the freedom of which class or classes in India are we especially striving for? Do we place the masses, the peasantry and workers first, or some small class at the head of our list? In my own mind it is clear that if an indigenous government took the place of a foreign government and kept all the vested interests intact, this would not even be the shadow of freedom.21

Russia showed what could be done by a government that was fully committed to socialism, and Nehru was impressed by its accomplishments. He thought that central planning, which replaced the chaos of markets with the cool judgement of scientists and engineers, was a particularly important innovation. Nehru saw in Russian planning the path that India would have to take if it was to become self-sufficient.

The idea was not to put up some factories to produce the goods which everyone needs, such as cloth, etc. This would have been easy enough by getting machinery from abroad, as is done in India, and fixing it up. Such industries, producing consumable goods, are called “light industries.” These light industries necessarily depend on the “heavy industries,” the iron and steel and machine-making industries, which supply the machinery and equipment for the light industries, as well as engines, etc. The Soviet Government looked far ahead and decided to concentrate on these basic or heavy industries…In this way the foundations of industrialism would be firmly laid, and it would be easy to have the light industries afterwards. The heavy industries would also make Russia less dependent on foreign countries for machinery or war material.22

Nevertheless, Nehru recognized that Russia and India were such different countries that India could not simply copy Russia’s initiatives.

Nehru recognized Russia’s shortcomings but readily excused them.

Much in Soviet Russia I dislike — the ruthless suppression of all contrary opinion, the wholesale regimentation, the unnecessary violence (as I thought) in carrying out various policies. But there was no lack of violence and suppression in the capitalist world, and I realized more and more how the very basis and foundation of our acquisitive society and property was violence. Without violence it could not continue for many days. A measure of political liberty meant little indeed when the fear of starvation was always compelling the vast majority of people everywhere to submit to the will of the few.23

Nehru was repelled by authoritarian government, whether it be that of Russia or the British Raj, but he firmly believed that radical social change could not be achieved without some degree of coercion.24 For Nehru, democracy — “the tyranny of the majority” — was the middle ground between authoritarian coercion and Gandhian nonviolence, and he held to it throughout his life. Democracy did not always serve him well. It reliably executes the will of the majority only when the citizens gather together to vote directly on the issues. India, with its federal organization and representative governments, did not operate so predictably.

Five-Year Plans

India’s development was guided by a series of five-year plans. The first three plans — covering 1951-56, 1956-61, and 1961-66 — were implemented while Nehru was prime minister.

The plans were drafted by the Planning Commission, an organization created in 1950 at Nehru’s request. Nehru, as both prime minister and the Commission’s chairman, effectively controlled its membership.

From 1955 to 1964, Nehru’s pivotal position permitted a handful of men to determine national economic and social policy and methods of development. During this period, the number of full-time members of the Planning Commission, including the deputy chairman, rarely exceeded five. A few part-time members brought the full complement of personnel up to nine or ten. Altogether, no more than twenty persons served on the Planning Commission between 1955 and 1964…Those having the longest association with the commission, and also the greatest influence on policy, had no formal economic training.25

The common thread in Nehru’s appointments to the Planning Commission was the political orientation of the members. The men who served on the commission were firmly committed, or at least sympathetic, to the blend of socialist goals and Gandhian methods that provided the intellectual framework for the approach to planned change. All of them considered the process of development in broader terms than economic growth, to include priorities for transformation of the social order and the establishment of an egalitarian and socialist pattern of modern society.26

Although the Planning Commission was originally intended to be an advisory body, it became “an extension of the prime minister’s authority.”27 As its chairman, Nehru drafted policy recommendations, and as prime minister, he presented these recommendations to an amenable cabinet.

India’s five-year plans were not like the Soviet Union’s five-year plans. The Soviet Union had nationalized all of its industry, allowing its planners to control every aspect of production. The planners’ goal, pursued relentlessly, was to develop heavy industry. Their restructuring of the economy led to

…the creation of mammoth industrial complexes in a few urban centers; the large shifts of population to the cities; the breakdown of small local communities; the disintegration of extended kinship groups; the application of mass production techniques; and the impersonal managerial device of a government bureaucracy…The concentration of all economic resources in the hands of the state constituted an ever present threat of political abuse, and carried with it the possibility of increasing regimentation.28

India’s socialists considered all of these things to be undesirable, and had no wish to replicate the Soviet Union’s development. Indeed, they were unwilling to take even the first step, the nationalization of industry. Their principal aim was to alleviate poverty, and they understood that the cause of Indian poverty was insufficient production, not unfair distribution. Nehru himself observed that in India, “there is only poverty to divide.”29 To produce more goods, India needed more capital — more factories and machinery — or equivalently, it needed a continuing flow of investment. Nationalization would discourage businessmen from making further investments, so it was renounced. The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948 ruled out the nationalization of existing or new industry for a period of ten years.

The injunction against nationalization aligned with the Gandhian “big tent” philosophy. Gandhi had argued that rural poverty could not be ended without the help of the zamindars, and his followers likewise argued that urban poverty could not be ended without the help of the industrialists. Sardar Patel, a long-time disciple of Gandhi and India’s first deputy prime minister, exemplified this attitude. He believed that India needed the industrialists’ skills as much as it needed their capital:

Nationalization is worthwhile only if the government can manage the industries efficiently. But this is difficult. We have neither the men nor the resources even to run our administration…Let those who have the knowledge and experience manage the country’s economy and increase the country’s wealth.30

Patel’s Gandhian sensibilities were a useful counterweight to Nehru’s socialism — but Patel died in 1950, and no equally influential Gandhian arose to take his place.

The first five-year plan was not finalized until very late in 1952, almost two years into the plan period, and was more of a practice round than an actual plan. It emphasized agriculture and rural development. The Second and Third Plans shifted the emphasis to industry. The Second Plan called for import substitution, which is a class of policies, not a single policy. Taiwan, for example, had experienced a severe shortage of foreign exchange in the early 1950s: its exports brought in so little foreign currency that it could not pay for the imports that it wanted. The government’s response was to identify imported goods that were produced using much labour and little capital, such as textiles and fertilizer. These were goods that Taiwan — a labour-rich, capital-poor country — could produce for itself. The government encouraged their domestic production to free up foreign exchange for other purposes. Import substitution was a relatively simple fix for a well-defined problem. By contrast, the goal of Indian import substitution was self-sufficiency, which would require large capital investment in a wide range of industries, including metals, power generation, and heavy machinery. This investment would draw heavily on the government’s limited revenue and its limited access to foreign exchange. And it would require decades, not years, of commitment.

Another significant feature of the Second and Third Plans was that they shifted responsibility for investment away from the private sector and towards the public sector. The Third Plan, for instance, called for 64% of investment to be in the public sector. The economy would, over time, shift substantially toward public ownership, even without nationalization.

Agriculture

Agriculture and rural development were emphasized in the first five-year plan. The Second and Third Plans shifted the focus to heavy industry, but called for so much additional spending that more money, not less, would be spent on rural issues. Despite this spending, the plans did not significantly alleviate rural poverty.

According to estimates made by the Indian Planning Commission in 1960/61 — after the first decade of planning — fifty to sixty percent of the rural population, or approximately 211 million people, could not afford minimum levels of consumption, calculated primarily in terms of caloric intake necessary to avoid the onset of malnutrition.31

By the time of the Third Plan, reports from two major funding sources, the Ford Foundation and the World Bank, had called for radical changes to India’s agricultural policies, and the World Bank had made such changes a precondition for further aid.

The chief impediments to a successful agricultural policy were the shortage of arable land and its radically skewed ownership distribution.

The majority of all rural households, approximately 61 percent, either owned no land, or small fragments of land, or uneconomic and marginal holdings…All of them together owned less than 8 percent of the total area. These were the recruits in the army of the chronically unemployed and underemployed…They could be contrasted with what passed for large landowners in India, the upper 13 percent of all households who had more than 10 acres and owned about 64 percent of the entire area, and the even smaller elite of the upper 5 percent having 20 acres or more, and owning 41 percent of the area…There were many fewer large farms than large landowners. Holdings in all size groups were subdivided into separate parcels that were scattered within and between villages…Holdings of 10 acres or more were commonly separated into seven or eight parcels of 2, 3, and 4 acres. “Large” landowners, therefore, tended to operate small holdings. They did not enjoy advantages associated with economies of scale.32

The prevalence of landless or land-poor peasants, coupled with the fragmentation of large holdings, led to complicated arrangements of tenancy, sub-tenancy, and sharecropping. Many landowners did not farm at all, preferring to enter into rental or sharecropping agreements in order to undertake other work.

There were two options (not mutually exclusive) for improving India’s agricultural productivity. One was to adopt “scientific” methods of farming, such as the use of new seed varieties and chemical fertilizer, the installation of small-scale irrigation systems, and the use of mechanized pumps and farm equipment. The other was to intensify the use of traditional farming methods, including “more careful attention to land levelling, seedbed preparation, weeding, line sowing, interculture, and more efficient techniques in collection and application of organic manures.”33 The belief that the full potential of traditional methods had not yet been realized rested on the observation that India’s yields were lower than those of other countries at the same level of development.

The prevailing allocation of arable land limited the effectiveness of both approaches.

They [landless and land-poor peasants] had neither the incentive nor the capacity to carry out labor-intensive production schemes that could increase yields within the traditional framework of production. Sharecroppers paying 50 percent or more of their output in rent provided the most obvious case. They rarely invested in modern inputs and they certainly did not lavish any extra attention on the cultivation of leased-in land. Nor was there much scope for carrying out overhead labor-investment projects — construction and maintenance of water courses, field channels, wells, tanks, drainage systems — which were so critical for increasing productivity through traditional techniques. Individuals were unable to undertake such land improvement schemes, and groups of landless and land-poor cultivators found no incentive to do so.

The patterns of land distribution and land tenure were only somewhat less serious obstacles in achieving higher levels of productivity through the introduction of capital-intensive technologies. Many “large” landowners, like small and marginal cultivators, found it uneconomic to invest in modem agricultural techniques. The large landowner was rarely able to realize the maximum return from his investment because the size of his operational holding was usually less than the optimum area for efficient cultivation using costly modern equipment. This was a pervasive problem in the rice areas, where the installation of minor irrigation works (percolation wells, pumpsets, and tubewells) was desirable to supplement supplies of water from surface irrigation projects, but the command area of the smallest mechanized works were a minimum of five to ten acres. Without assured water, large cultivators, no less than small and marginal holders, hesitated to make higher outlays on the optimum application of fertilizers and pesticides, when the investment was likely to be lost if rains were inadequate or there was flooding. Some landowners, of course, simply had no interest in land development or maximizing output from their holdings. Under existing tenurial arrangements, they effortlessly received reliable income by collecting rent and interest on loans. 34

If the distribution of ownership were such an impediment to progress, would not a “land to the tiller” program kickstart India’s agriculture? Taiwan in the 1950s and Vietnam in the 1970s successfully deployed programs of this kind, but India had to contend with an absolute shortage of arable land. Suppose that the government set an upper limit on each household’s land holdings, expropriated all of the land above the limit, and distributed the expropriated land to landless and land-poor peasants. In the eastern part of India, imposing a cap of 7.5 acres would allow each peasant household to farm 1.5 acres of land. But holdings of at least 7.5 acres were required to profitably adopt modern farming methods, and also to ensure that the household had an acceptable standard of living.35 The recipients of redistributed land would remain in dire poverty.

A policy of consolidating fragmented farms would also be problematic. Consolidation by the larger landowners would allow them to operate more efficiently, but would displace tenants and sharecroppers, forcing them into the legion of unemployed or underemployed labourers.

For Nehru and the Planning Commission, agricultural policy had to be consistent with two long-term goals. Nehru had called for the elimination of poverty. Since three-quarters of India’s population lived in rural areas, most of India’s poverty was rural poverty. To eliminate it, agriculture had to be made more productive. But Nehru was also committed to moving toward a more equal society. Agricultural policy must not serve the needs of the more prosperous farmers at the expense of the poorest peasants.

The First Plan provided limited support for the adoption of modern farming methods, an initiative that principally benefited large landowners who had reliable access to water, but the plan’s major agricultural initiative was Community Development, a program designed to change rural India’s institutional structure over a period of a decade or more. Community Development received about a quarter of the funds allocated to agriculture; under the Second Plan, it would receive almost half of the funds.36

Community Development had three interconnected goals. The first goal was to give landless and land-poor peasants access to land by establishing co-operative farms. Ideally, a cooperative farm would encompass all of a village’s arable land and be managed by the farmers themselves. The farm would be both large and consolidated, allowing modern techniques to be profitably deployed. The absence of landlords and other intermediaries meant that the cultivators would receive the full benefit of their labour, increasing their incentive to exploit traditional techniques. By the mid-1950s, the claim that cooperative farming would double agricultural yields was commonplace.37

The co-operative farms would not be established through coercion; instead, the peasants would come to realize their value through “persuasion and education” and freely choose to create them. The decade-long timeline reflected the time required for the peasants’ beliefs to change. It also reflected Nehru’s desire to avoid conflict within a party that represented both the peasant and the landowner. So long as the transition to cooperative farming was relegated to the indefinite future, the landowners could be placated.

The second goal was to create fully democratic institutions at the village level. All villagers would be encouraged to involve themselves in the village’s political life. The villagers would elect their panchayat, and the panchayat would become responsible for all local decisions, including the planning and implementation of local infrastructure projects. The second goal, like the first, involved a change in peasant behaviour and would not be achieved quickly or easily.

The third goal was to develop each village’s infrastructure using the unpaid labour of its unemployed or underemployed peasants. It was expected that the shift toward cooperative farming, coupled with the political empowerment of the peasants, would cause the peasants to see themselves as the primary beneficiaries of local infrastructure projects. They would work out of self-interest.

None of these goals was achieved. Only a small number of cooperative farms were set up, possibly because a farm created by amalgamating small holdings would be neither large enough nor dense enough to employ modern techniques. To be successful, a cooperative farm needed the larger landowners to buy-in, and they had no incentive to do so. Furthermore, these landowners were politically well-connected. Their influence ensured that the state governments steadfastly resisted cooperative farming. As for the second goal, the political empowerment of the villagers was intended to be a means of overthrowing the power of the local elites, but the elites proved quite capable of protecting their own interests.

The effective units of social organisation in most Indian villages were hierarchical in structure, based both vertically on patron–client relationships and interlinked markets for credit and labour, and horizontally on bonds of common social, ritual or economic status. As a result, group-based and interest-based competition for resources within the village undermined the integrative purpose of the Community Development programme, and also weakened the impact of…the new institutions of panchayati raj (village administration).38

Expectations that the landless and land-poor peasantry could use the new village cooperative and panchayat institutions constituted on principles of universal membership and mass suffrage to shift the balance of income, status, and power away from the dominant landed castes proved to be unjustified. On the contrary, the propertied classes, far from being outflanked by popular majorities, showed themselves adept at manipulating the fragmented peasantry along divisions of kinship, caste, factional, and economic lines…Deprived of outside leadership and organization, the peasantry continued to acquiesce in the domination of proprietor groups. Indeed, existing vertical structures were actually strengthened. The dominant landed castes, increasing both their economic and political leverage, gained access to additional resources of credit and scarce agricultural inputs introduced into the villages by the Community Development program. They enlarged their role as intermediaries in relationships between the village and outside authorities in both the administration and the ruling party.39

Finally, Community Development was only moderately successful at initiating local infrastructure projects. Since neither cooperative farming nor the peasants’ political empowerment had taken hold, there was no change in the peasants’ incentives.

Efforts to mobilize local manpower and resources for construction of capital projects met with little success. While richer farmers generally could contribute cash to village projects, subsistence cultivators and landless laborers, of necessity, were asked to donate labor. Local officials quickly discovered it was not possible to mobilize idle manpower for unpaid work on a “community” project in minor irrigation or soil conservation when the benefits were disproportionately skewed toward the larger landowners. Difficulties arose even with respect to use of surplus manpower for the construction of social amenities projects, such as approach roads, drinking-water wells, community centers, and libraries. Cultivators were the greatest beneficiaries of new roads linking the village to nearby markets; and in situations of social discrimination, lower castes might be excluded from the full enjoyment of a community center, panchayat house, or a drinking-water well. Poorer families were also illiterate; they had no need for libraries, and in some cases they could not afford to send their children to school.40

The Second Plan’s emphasis on industrial development increased the pressure on the agricultural sector. The industrial workers needed food, the factories needed raw materials, the government needed agricultural exports to earn badly needed foreign exchange. The slow pace of Community Development was inconsistent with the anticipated pace of industrial development, and the planners looked for ways to accelerate it.

Some land reform had already been undertaken by the states:

After independence, the different states passed legislation abolishing the zamindari system which, under the British, had bestowed effective rights of ownership to absentee landlords. The abolition of zamindari freed up large areas of land for redistribution…

After the end of zamindari, the state vested rights of ownership in their tenants. These, typically, came from the intermediate castes. Left unaffected were those at the bottom of the heap, such as low-caste labourers and sharecroppers. Their well-being would have required a second stage of land reforms, where ceilings would be placed on holdings, and excess land handed over to the landless. This was a task that the government was unable or unwilling to undertake.41

The Second Plan advocated exactly this sort of cap-and-redistribute legislation — but the constitution assigned the responsibility for land reform to the states, so it could do no more than advocate. The design of the legislation was necessarily left to the states.

This put a brake on ceiling legislation, which in most cases was delayed until the early 1960s, and which set initial maximum levels at generous quotas of 30 acres or more. Large landholders had ample time and opportunity to exploit the many loopholes that remained in the ceiling legislation, especially by distributing nominal ownership of land among different members of the family.42

The planners decided to “force the pace of agrarian reform” by putting forward the “Nagpur resolution” (1959). The resolution advocated the completion of all land reforms within one year, and linked the land reforms to cooperative farming. All of a village’s arable land would become part of a cooperative farm under the management of the panchayat. Landowners would retain their property rights, and get shares of the farm’s produce proportional to their shares of the land. Landless labourers would get shares of the produce proportional to their shares of the work.

The Nagpur resolution put the cat among the pigeons. So long as cooperative farms had been consigned to the indefinite future, Nehru had been able to minimize the conflicts within Congress’s “big tent.” Now landowners were confronted with a proposal that fell just short of expropriation. Minoo Masani — a Congress member and legislator, a former socialist, now a democratic socialist — explained their dismay.

When the boundaries of the farm have been uprooted, when tractors are running over that land which was once six, eight, ten or twenty farms, the right of property will mean a mere piece of paper given to the peasant to console him by saying, “You once owned so many acres; your property is still intact.” But after a while, the question is raised, “Why should this man who is not working hard or not doing as much as the other fellow draw a large share because he once owned some land?”…The functionless owner is no owner. His property has actually been taken away from him without telling him so and he is being fobbed off with a scrap of paper which a future government will have no hesitation in tearing up, because his use to society ends on the day on which the farm ceases to be his…I have no hesitation in asserting that the resolution passed at Nagpur, whether those who passed it are aware or not, is a resolution for collective farming of the Soviet-Chinese pattern, and not for genuine cooperative farming.43

Masani left Congress to become a founding member of Swatantra, a conservative party. Many landowners and entrepreneurs joined the new party, but many remained in Congress, where they successfully opposed the planners’ initiative. Later, in 1964, large-scale land reform was made prohibitively costly by a law requiring that cultivating owners receive market-value compensation for any loss of land or land rights.

Nehru never gave up on cooperative farming, saying “I shall go from field to field and peasant to peasant begging them to agree to it, knowing that if they do not agree, I cannot put it into operation.”44 But it wasn’t the peasants who stood in his way; it was the landowners and the entrepreneurs.

Industry

Nehru believed that a country that could not produce strategic goods — weapons, metals, machinery — would always be subject to the intrigues of the countries that could:

If we do not develop heavy industry here then we either eliminate all modern things such as railways, airplanes and guns, as these things cannot be manufactured in small-scale industry, or else import them. But to import them from abroad is to be the slaves of foreign countries. Whenever these countries wished, they could stop sending these things, bringing our work to a halt; we would thus remain slaves.45

To ensure India’s security, Nehru intended to rapidly develop India’s heavy industry. He could imagine no other path.

If we really wish to industrialize, we must start from the heavy, basic, mother industries. There is no other way. We must start with the production of iron and steel on a large scale. We must start with the production of the machine which makes the machine.46

The Second and Third Plans called for a surge in capital formation. Investment, which had been less than 7% of GDP before independence, rose to 13% of GDP during the First Plan and to more than 17% of GDP during the Second and Third Plans.47 Most of the additional investment was made by the government and allocated to heavy industry. The Second Plan assigned 70% of industrial spending to the metal, machinery, and chemical industries; the Third Plan assigned 80% of industrial spending to the same industries.48

The roles to be played by the public and private sectors were delineated by the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956. It identified three categories of industries. Schedule A industries were those in which only the state could operate, or in which only the state could establish new facilities (either alone, or at the state’s initiative, in cooperation with private firms). The state would be the sole provider of arms and ammunition, atomic energy, railways, and air transport. It would have the exclusive right to establish new facilities in another thirteen industries, including iron and steel, shipbuilding, aircraft production, telecommunications equipment, oil refining, mining of coal and other strategic minerals, production of heavy industrial machinery and heavy electrical equipment, and production and distribution of electrical power. Schedule B industries were those in which the private sector would be allowed to operate, but in which the state intended to aggressively establish new facilities. There were twelve industries in this category, including machine tools, antibiotics and other essential drugs, synthetic rubber, and fertilizer. Private firms in these industries were subject to regulation to ensure that their actions were consistent with government policy. The industries not listed in Schedules A and B were open to the private sector, although the firms were still subject to certain forms of government regulation.

The tools needed to regulate the private sector were already in place. The Industries (Development and Regulation) Act of 1951 had given the government the right to intervene in almost every decision made by private firms in scheduled industries.49 The Act’s product licensing provisions alone included the following restrictions:

- All existing industrial undertakings in the scheduled industries were required to register in a manner prescribed by the central government;

- All new industrial undertakings with investment in fixed assets (building, land and plant, and machinery) above a stipulated threshold in the scheduled industries were required to obtain a license specifying the product, location, the minimum standards in respect of size, and any other conditions prescribed by the central government;

- No new article was to be produced by an undertaking without obtaining a license or modification of an existing license;

- No substantial expansion or change of location of an industrial undertaking was to be undertaken except under a license issued by the central government.50

The Act also gave the government the right to set the prices of goods produced in the scheduled industries, as well as control over their “distribution, transport, disposal, acquisition, possession, use or consumption.” Finally, the Act authorized the government to investigate unexpected events such as “a substantial fall in output, marked deterioration in product quality, unjustified increase in price, and management of the undertaking in a manner detrimental to the scheduled industry or public interest,” and the power to take appropriate corrective action.51 The Act initially applied only to firms in the scheduled industries, but

… its scope grew much wider after the balance-of-payments crisis forced the government to adopt strict foreign exchange control in 1957. Regardless of their size and industrial classification, undertakings found they could no longer access foreign exchange for machinery and raw material imports unless registered under IDRA 1951.52

The Second and Third Plans were underfunded when implemented. The Second Plan was kept afloat by foreign aid. The Third Plan, on the other hand, had to adapt to shocks in the form of two border wars and two severe droughts. The costs associated with these events depleted the government’s revenue, forcing the termination of many projects envisioned by the Plan.

The Second and Third Plans had been designed to achieve two objectives. One was to make India more self-sufficient, and in this regard, the policy was successful: almost 40% of new machinery had been imported in 1960, less than 15% was imported in 1970.53 The other was for the state to gradually increase its ownership of the economy’s “commanding heights” by being the only investor in Schedule A industries and the predominant investor in Schedule B industries. The plans were less successful in this regard. The state’s share of investment under the First Plan had been 46%. The Second Plan set a target of 61% and achieved 54%. The Third Plan set a target of 64% and achieved 50%.54 The government failed to become the predominant investor in Schedule B industries.

Licenses issued to Schedule B industries from 1956 to 1966…went overwhelmingly to private-sector enterprises. The entire development of the aluminum industry took place in the private sector. The private sector also begged 226 out of 235 licenses in machine tools, 334 out of 335 in plastics, antibiotics, and other essential drugs, 36 out of 46 in fertilizers, and 184 out of 199 in drugs and pharmaceuticals.55

Patel’s contention that India needed the entrepreneurs’ skills as well as their capital proved to be correct.

The plans, even if somewhat successful, weren’t necessarily wise. India’s comparative advantage lay in agricultural goods and simple consumer goods, not in the products of heavy industry. If India had produced more of the former goods, sold them abroad, and used the proceeds to purchase capital goods, it would have ended up with more capital goods than it did by attempting to produce them at home.56 The cheapest way of laying down an industrial base was to trade for it.

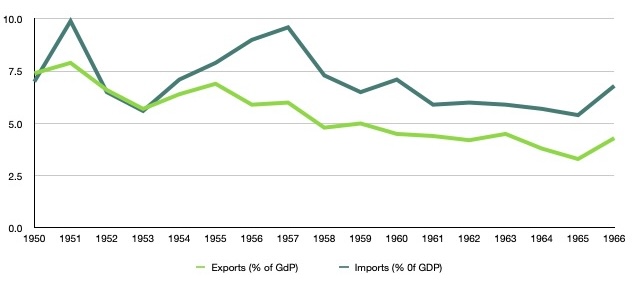

There is a second way in which investing less in heavy industry and more in agriculture and light industry would have been beneficial. It involves the foreign exchange market. Indians buying foreign goods pay for them with the currency of the seller’s country; foreigners buying Indian goods pay for them with Indian rupees. The two parties obtain each other’s currency by trading in the foreign exchange market. Their trades produce roughly synchronous movements in India’s exports and imports, as shown in the figure above.57 If India’s exports fall, for example, foreigners sell less of their own currencies to obtain Indian rupees. Since Indians acquire less foreign currency, they are forced to reduce their purchases of foreign goods, meaning that India’s imports also fall.58

In the Nehru era, India’s exchange rate was both fixed and overvalued: at the official exchange rate, more rupees were offered for sale by Indians than were purchased by foreigners. The Indian government was initially able to deal with this imbalance by drawing down its foreign exchange reserves, especially the pound sterling reserves held in London. By 1957 so much of India’s foreign exchange reserves had been lost that the government was forced to restrict imports. It restricted the private sector’s imports by imposing import licensing, and it restricted its own imports by abandoning projects that had been included in the Second Plan.

The planners were forced to limit allocations of foreign exchange to a small list of “core” projects in iron and steel, coal, power, railways, and ports. Completion of a number of other industrial schemes in the public sector, including the large fertilizer plants, had to be delayed.59

The scarcity of foreign exchange was partly due to the decision to prioritize investment in heavy industry. A more balanced investment plan could have mitigated the foreign exchange shortage in two ways. First, imports of labour-intensive goods could have been reduced by producing more of these goods at home. Second, exports of simple goods could have been expanded; by the mechanism described above, additional exports would have enabled more imports.

Arvind Panagariya has identified further ways in which an expansion of viable export industries would have been beneficial.

Specialization in a handful of products, which can be partially exchanged in the world markets for products not produced at home, allows the firms to achieve high productivity through several channels:

-

Insofar as the country specializes in the export of labor-intensive manufactures in the early stages of development and is consequently able to import machinery and other capital-intensive products, it is better able to utilize its scarce capital.

-

Firms that operate in export markets are inevitably exposed to competition with the most efficient producers in the world. This fact forces them to continuously update their technologies, management practices, and product quality to remain competitive.

-

Large world markets allow the exporting firms to achieve a scale that makes it attractive for them to employ machinery, which in turn creates skills and raises labor productivity and wages. Use of extra machinery does not undermine the employment objective, since employment per unit of capital is large in labor-intensive products that the country exports, and the vast world market allows exporting firms to operate on a large scale.

-

World markets give firms access to high-quality inputs and machinery, which in turn allows them to produce high-quality products demanded by sophisticated global customers.

-

Continuous upgrading of technology and management by export-oriented firms gives rise to continuous upgrading of skills and thus better prepares the workforce for the next generation of technologies and innovations in management techniques.

Confined predominantly to the domestic market in the early decades, Indian firms remained stuck in old technologies, low-quality products, and low levels of productivity. The greatest loss of efficiency was in light manufactures, precisely the products in which the country had potential comparative advantage because of its vast labor force.60

The Second and Third Plans gave rise to a regulatory burden that became increasingly onerous.

Until the end of the Second Plan, the economy was still relatively small and simple, and the top bureaucracy, efficient and honest. This would mean that the bureaucracy could make decisions on the applications for licenses relatively expeditiously. Moreover,…the government’s attitude toward the private sector was still flexible and pragmatic rather than rigid. It was only during the 1960s, when the economy in general and the industrial sector in particular became more complex and the objectives sought to be achieved through licensing multiplied, that the administration of licensing turned progressively more chaotic, arbitrary, and subject to lobbying and corruption.61

It became clear that Nehru’s vision of an economy building outward from a solid base of heavy industry would not be realized. The socialists in Congress’s “big tent” were frustrated by its failure, the entrepreneurs by its constraints.

The End of the Nehru Era

There was widespread dissatisfaction with India’s growth prospects by the time of Nehru’s death in 1964. The attempt to raise agricultural productivity through social change had failed, a fact underlined by the reappearance of famine during the droughts of 1965 and 1966. The growth rate of the industrial sector was well below the target of 14% per year.

The stagnancy of the Indian economy had serious implications for both the unity of Congress and the quality of government.

The limitations of political accommodation as an integrative device, given an economy of scarcity and weak national commitments, took on tangible form by the early 1960s…Growing demands on static resources led to bitter internal disputes inside the Congress party. Factional alliances frequently broke down. There were constant rivalries for control over the party machinery…[The party leadership] kept the peace by dividing and redividing among rival groups the limited resources of patronage and power available.

This was not the only sign of political decay…Standards of honest and efficient administration precipitously declined. Officers of the police, the judiciary, the state and local revenue and development services, and even the vaunted Indian Administrative Service, were all engaged in selling influence (often at fixed prices and graded fees) to individuals ranging from industrialists, contractors and suppliers, traders and large agriculturists, to the chief ministers and ministers of the state and central governments. As corruption became institutionalized into a distributive device, those who could not afford to pay found themselves at the bottom of the list in the allocation of access to “public” goods and services.62

These difficulties did not signal the end of Indian socialism — it had another quarter-century to run.

Go to: Indian Socialism: 1966-1984

- Arvind Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant (Oxford, 2008), p. 22. Panagariya does not include himself among these analysts: he has elsewhere described Nehru’s economic policies as a “resounding failure” (Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 1). ↩

- Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant, p. 23. ↩

- M. K. Gandhi, My Socialism (Navajivan Publishing House, 1959), p. 18. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, p. 52. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, pp. 44-5. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, p. 21. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, pp. 21-2. ↩

- Gandhi, quoted by Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 10. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, p. 4. ↩

- Gandhi based the concept of trusteeship on “the ancient Hindu concept of dharma — the notion of moral duty allied to relative standing in the caste hierarchy,” under which “the well-to-do classes” were obligated “to do yagna or sacrifice, and to use their wealth charitably on behalf of the poor.” (Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 39. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, pp. 42-3. ↩

- Gandhi, My Socialism, p. 32. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, pp. 44-5. ↩

- Jawaharlal Nehru, An Autobiography (Oxford, 1936), p. 52. ↩

- Nehru, An Autobiography, p. 35. ↩

- Nehru, An Autobiography, pp. 362-3. ↩

- Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism was published in 1917, so Lenin’s ideas on colonialism were “hot off the presses” when Nehru encountered them. ↩

- M. K. Gandhi, Village Industries (Navajivan Publishing House, 1936, reissued 1960), p. 11. ↩

- Nehru, An Autobiography, p. 527. ↩

- Nehru, excerpt from a 1928 speech, quoted by Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 20. ↩

- Nehru, quoted by Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 53. ↩

- “The Piatiletka, or Russia’s Five Year Plan” (written 1933), in Nehru, Glimpses of World History (Penguin, 2004). ↩

- Nehru, An Autobiography, p. 361. ↩

- Nehru did not share Gandhi’s belief in the unlimited potential of nonviolent disobedience. Gandhi was prepared to wait for the zamindars to do the right thing; Nehru preferred to expropriate their land holdings. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 114. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, pp. 114-5. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 113. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 16. ↩

- Nehru, quoted in Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 38. ↩

- Sardar Patel, quoted in Shakti Sinha and Himanshu Roy, eds., Patel: Political Ideas and Policies (SAGE Publications, 2019), p. 213. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 4. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 97. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 96. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 98. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India (Cambridge, 2013), p. 159. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 157. ↩

- A. P. Jain recalls that in 1956, when he was serving as the minister of agriculture, “The Planning Commission had adopted the idea that you can raise any amount of food by utilizing surplus labor power…We had begun to believe that by the sheer utilization of the waste labor power, you can achieve anything and everything.” (Jain, quoted by Frankel, India’s Political Economy, pp. 141-2) This belief stemmed from the huge productivity gains claimed by Chinese communes during the Great Leap Forward. As discussed here, these gains were actually quite small, perhaps negligible. The communes were subject to adverse incentives and were notoriously inefficient; they were the target of one of Deng Xiaoping’s earliest and most important reforms, the household responsibility system. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, pp. 157-8. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 201. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 189. ↩

- Ramachandra Guha, India after Gandhi (Picador India, 2007), pp. 216-7. ↩

- Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, p. 160. ↩

- Minoo Masani, quoted by Frankel, India’s Political Economy”, pp. 166-7. ↩

- Nehru, quoted by Frankel, India’s Political Economy”, pp. 187. ↩

- Nehru, quoted by Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 40. ↩

- Nehru, quoted by Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 40. ↩

- Data from Table 10.2 of Bishnupriya Gupta and Tirthankar Roy, “From Artisanal Production to Machine Tools: Industrialization in India over the Long Run,” in Kevin O’Rourke and Jeffrey Williamson, eds., The Spread of Modern Industry to the Periphery since 1871 (Oxford, 2017). ↩

- Jagdish Bhagwati and Padma Desai, India: Planing for Industrialization (Oxford, 1970), p. 85. Here, the chemical industry includes oil refining and fertilizer production. ↩

- IDRA 1951 was the implementation legislation for IPR 1948, a precursor of IPR 1956 that set out a shorter list of scheduled industries. ↩

- Arvind Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, pp. 95-6. ↩

- Arvind Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 97. ↩

- Arvind Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 96. ↩

- Bishnupriya Gupta and Tirthankar Roy, “From Artisanal Production to Machine Tools,” p. 245. ↩

- Arvind Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant, p. 34. ↩

- Arvind Panagariya, The Nehru-Era Economic History and Thought, p. 106. ↩

- The gains from trade would have been quite substantial. Sudha Shenoy believes that the return on an investment in agriculture was roughly three times greater than the return on an investment in heavy industry, and an investment in textile mills was roughly twice as great. (Shenoy, India: Progress or Poverty?, Institute of Economic Affairs, 1971, pp. 69-70.) ↩

- This figure is my reconstruction of too-blurry-to-use copies of Figures 2.2 and 2.3 in Arvind Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant. ↩

- Several factors caused changes in imports and exports to be only roughly synchronous, including shifts in international capital movements, foreign aid (which gave the Indian government direct access to foreign currencies or foreign goods), and changes in India’s foreign exchange reserves. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, p. 148. ↩

- Panagariya, New India: Reclaiming the Lost Glory (Oxford, 2020), pp. 16-7. ↩

- Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant, p. 40. ↩

- Frankel, India’s Political Economy, pp. 202-3. ↩